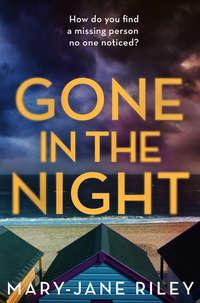

Читать онлайн книгу «Gone in the Night» автора Mary-Jane Riley

Gone in the Night

Mary-Jane Riley

A twisty and compelling thriller perfect for fans of C L Taylor, K L Slater and B A Paris. Some secrets are deadly… When the victim of a car crash begs journalist Alex Devlin for help before disappearing without trace, Alex finds herself caught up in a mystery that won’t let her go. Determined to find the missing man, she is soon investigating a conspiracy that threatens some of the most vulnerable members of society. But will Alex be prepared to put her own life on the line to help those who can’t help themselves?

Gone in the Night

MARY-JANE RILEY

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

KillerReads

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Mary-Jane Riley 2019

Cover design Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover images © Shutterstock.com (https://www.shutterstock.com/discover/stock-image-v2?kw=shutterstock&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIiZHuqdOL4QIVab7tCh1gpgzMEAAYASAAEgK-m_D_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds)

Mary-Jane Riley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008340254

Version: 2019-03-27

For my parents, who did so much to encourage my love of books

Table of Contents

Cover (#ue3f711cb-2d27-5f07-ba3e-c1ef55d5faa6)

Title Page (#u8df214cd-3d7a-5e2d-8165-d854bbaa4ba5)

Copyright (#ud8a7f644-460f-598f-a90d-d6bec95906e3)

Dedication (#uefc2182f-2252-5f0d-9f4e-73b334a947d9)

Prologue (#u9d82762f-8833-54fd-8058-39688aed380f)

Chapter One (#u7164c546-598d-5836-8ecb-4b6bf933ee09)

Day One: Morning (#ud619f5e8-8a5f-5fef-97fe-86e2b9c18b59)

Chapter Two (#ueb6adf4c-3c56-5fe3-996d-15c72aa43ea5)

Day One: Evening (#u99bee92f-d2cc-5b3a-92f5-a39232998877)

Chapter Three (#uefe8b4b5-7091-5ef1-8e20-9748ca8de369)

Day One: Evening (#u6cdadf2c-60cb-567b-a155-bb533e0e1de8)

Chapter Four (#u9b688474-ea3b-5aa3-b98b-659c28def472)

Day One: Late Evening (#uf96af620-d90f-5a89-b43b-5a2a601ab05e)

Chapter Five (#ud23aa2e7-4a06-52e8-bdc0-f94c99e2bc94)

Day One: Late Evening (#ud376f1b3-d5f6-5a8e-a876-2264b8b4f743)

Chapter Six (#ufd02f5a5-6134-5179-bd22-8250163acea5)

Day One: Late Evening (#u1eb2c3c6-c1a8-5f64-a2f8-fd5224fca437)

Chapter Seven (#u3b0b44e6-e2a7-5dc7-8421-f5de1b3a97d9)

Day Two: Morning (#uab9da5ee-6936-5e98-8352-62f68b72c758)

Chapter Eight (#u305c5ed0-8d64-5fb3-9177-410dbc0bf88b)

Day Two: Morning (#uf3591399-718f-52e1-8e6e-97a1ffb75705)

Chapter Nine (#ue8243c93-c7fb-5649-83f8-fd8cae93db03)

Day Two: Morning (#u9f3e6741-9c62-50e4-b961-db273a90f3d7)

Chapter Ten (#ubee5cd97-c054-5a91-957b-a17ae6a775d3)

Day Two: Morning (#ue03d1c55-180b-574d-8bb8-004f8f76992d)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Two: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Two: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Two: Late Afternoon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Two: Late Afternoon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Two: Late Afternoon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Three: Early Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Three: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Three: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Three: Late Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Three: Late Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Three: Evening (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Four: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Four: Late Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Four: Late Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Four: Evening (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Four: Evening (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Five: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Five: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Five: Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Five: Afternoon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Five: Afternoon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Five: Evening (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Six: Late Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Six: Afternoon (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Six: Late (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Six: Late (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Six: Late (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Seven: Early Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Seven: Early Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Seven: Early Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Seven: Early Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Seven: Early Morning (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Three Weeks Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mary Jane Riley (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#u85a50a7e-2e82-5807-9488-b976b23d5c46)

He watched them kill her. Not a needle in her arm, not a quick bullet in the brain, but blows to the head with a large, heavy rock – one blow to each temple. Then they rolled her over on the plastic sheeting they had laid on the floor and stove in the back of her head. The iron, meaty smell of her blood mingled with the sweat of her killers.

He tried to remember her name.

They would throw her into the sea and let the water and the rocks cover up their dirty work. She might never be found – after all, the sea doesn’t always deliver the dead back to the living.

Or maybe they would take her to one of the many out of the way foot crossings on the Norwich to London railway line. He didn’t have the strength or the will to intervene. Not yet. All he could do was watch and commit it to his memory. Commit that last look she gave him, that last sad, defeated look, to his memory.

By the time her body was found, there would be no evidence that she had been murdered.

CHAPTER ONE (#u85a50a7e-2e82-5807-9488-b976b23d5c46)

DAY ONE: MORNING (#u85a50a7e-2e82-5807-9488-b976b23d5c46)

Cora Winterton dabbed concealer under her eyes and applied shocking pink lipstick to her lips. She peered at herself in the mirror, then grimaced. She looked terrible. Nothing a few good nights’ sleep and some decent meals wouldn’t cure, but she wasn’t going to get those any time soon. Working nights was a bitch. Especially when she didn’t get much sleep during the day. Couldn’t do it. Even after all these years her body clock wouldn’t adjust to hospital shifts. But she wasn’t going to put it off any longer. She couldn’t pretend any more that Rick had moved sites or was staying in a hostel. Besides, she had been around all the obvious places, and plenty of the not so obvious ones and there was still no sign of him. But she had to check once more, there were still some people she hadn’t talked to.

Where was he?

Her head began to swim. She leaned forward and grabbed the sides of the washbasin, trying to breathe deeply and evenly. Lack of food, lack of sleep, worry about her landlord putting up her rent – all of that. More deep breaths and her head felt better.

Two cups of coffee, one cigarette and another application of lipstick later and Cora emerged into the misty gloom of the early morning. It was a good time to see the people she wanted to talk to – before they moved on to start their begging in shop doorways, or to find breakfast at one of the hostels in the city. She hurried down the steps and out onto the pavement, striding along to the underpass, glad she’d brought her umbrella.

With its walls of graffiti and stench of urine, the underpass linking her end of town with the shopping area was a favourite spot for the dispossessed and the vulnerable. Often it was littered with cardboard, empty drinks cans and bottles, old bits of clothing used as bedding, sometimes used needles. Although there had been an attempt to make the bare concrete walls more cheerful by covering them with paintings of Picasso-like figures in lurid colours, Cora often thought someone could die down here and never be noticed. Today it was the rowdy crowd, drinking cheap cider and knock-off spirits, leaning, or in some cases sagging, against the wall.

‘Corrrrrra.’

‘Hey, Tiger, how are you?’ She smiled at the man who had pushed himself away from the wall and staggered towards her, ignoring the catcalls from the other men and women. ‘You’re up early.’

‘Keepin’ warm,’ he said, holding a can aloft. ‘Pissin’ freezin’. Coppers moved us on this mornin’. Honestly, no bleedin’ hearts in them.’

‘Can I get you a coffee?’ she said. ‘A bit of breakfast?’

‘Nah you’re all right. Bit of cash’d be nice.’

‘Tiger—’ She shook her head.

‘I know, I know, I’d piss it up against the wall.’ He cocked his head to one side. ‘Are you still lookin’ for Ricky-boy?’

‘Yes. Why, have you see him?’ Her heart leapt.

He shook his head. ‘Nah. We miss him though, don’t we?’ he shouted out to the others.

A general rumble of noise floated around the underpass. Tiger shrugged. ‘Sorry. Can’t help you. He’s a good mate, though. Find him soon, yeah?’

‘It’s okay,’ said Cora, ‘there are plenty of other places I can look.’ The familiar darkness settled around her head. She was never going to find him, but she had to keep looking.

And that was the depressing thing, she thought, as she tramped around the city in the drizzle that was getting harder and colder by the minute, there were plenty of other places to look, even in a city like Norwich which never used to have a homelessness problem. Now it seemed to be everywhere. People sleeping in shop doorways, in car parks, alleyways, even by the traffic lights outside the station.

And it was Martin, outside the railway station, bundled up in his sleeping bag, covered with old tinfoil, and lying on a bed of newspaper and used pizza boxes with his beloved dog, Ethel, who gave her the first bit of hope since Rick went missing.

‘Yeah,’ said Martin, sitting up and accepting a cigarette and a takeaway coffee from her with trembling fingers. ‘I saw Rick ’bout two weeks ago. Before I went to Yarmouth. Piss poor place that. Two weeks was enough.’ He hunched his shoulders against the wet.

Cora nodded. That was the last time she’d seen her brother, when she had tried to persuade him to spend at least one of the freezing nights in a homelessness shelter.

‘He had a smoke with me. Told me ’bout some men who’d come calling.’

‘What sort of men?’

Martin tugged the sleeping bag around his neck trying to stop the rain trickling down. He shivered. ‘You know, well-dressed, well-fed types. One of them wearing a suit, for fuck’s sake. Looked like Mormons. Wanted to know about him.’

Cora frowned. God-botherers? Do-gooders? Or the men they were expecting to see? ‘And what did he tell them?’

An early morning commuter tossed a few coins in the bowl that was always by Martin’s side. Ethel sniffed the bowl, but turned away when she saw there were no tasty biscuits in it for her.

Martin looked down, focused on the ground. ‘He said he told them he had nobody and he didn’t want no help from no one, unless they had a job to offer him.’

There it was. The guilt that squeezed her, that had made her search frantically for her brother whenever she could these past few days, that had interrupted what little sleep she had managed to grab for herself. The argument she’d had with Rick the day before he disappeared. When she’d told him she was done with helping him. It was time to call it off. She was frightened about what might happen.

It had started out as nothing really, as many arguments do. She had sought him out at his usual spot behind the solicitors off Unthank Road. Two of the lawyers looked after him occasionally, giving him food and coffee. Cora was forever grateful to them. That day she had gone to find him, determined to persuade him to have his hair cut – had offered to pay. There was a new Turkish barbers that had opened, she told him. They would do the lot. A wash, a cut, even a beard trim. Why would he want that, he’d said, he was perfectly happy with how he looked. It was necessary now, she knew that, he told her, shaking his head.

Cora had wanted to cry. Rick’s hair and beard were long and matted. Grimy. She hated that ratty beard. It symbolized how far they had fallen. He looked uncared for, unkempt. And she told him so.

‘I live on the streets, Cora. That’s what happens,’ he told her. ‘This is what I wanted. And now it’s perfect.’

She wanted to stamp her foot. ‘But you don’t have to. We can stop this. You can come home with me.’ She’d had enough.

‘No.’ He had that steely look in his eyes.

She knew she ought to stop, but she couldn’t. ‘Rick, I don’t want to do this anymore.’

‘Well, tough. Because I do.’

‘I can’t bear it. I can’t bear to see you on the streets with no one to care for you and no one to love you. I want you with me.’ She dashed away the tears that were trickling down her cheeks.

‘I thought you understood, Cora.’ His voice was hard. ‘This has to be done. This is my life now.’

‘I don’t know why you’re punishing yourself,’ she whispered.

‘Yes, you do.’

‘Please, Rick. Come home with me. Or at least let me find you a place in a shelter for a few nights.’

‘Stop it.’ He sighed. ‘Cora, this is exactly what you do. You come here offering to pay for me to have my hair cut, trim my beard, probably put pomade or whatever that stuff is on it, but it would make a nonsense of everything. It would make a nonsense of my life. Of our lives. Of what I need to do. I have a purpose. Leave it, Cora, leave me alone, let me get on with it, like we agreed.’

‘I want us to be together. I’m not strong enough without you,’ she whispered.

‘You are. You’re stronger than anyone. Now, leave it, Cora, for fuck’s sake.’

And she had seen that anger in his face, the anger that could spill over into something altogether more frightening, and she had turned and left. Almost running in her haste.

‘That’s right, Cora,’ he shouted after her. ‘Run away. Just like you always do.’

She stopped and turned. ‘You know what, Rick? You’re a loser. You think you’re making life easier for me? Well you’re not. You’re bloody not.’

And since then she hadn’t been able to find him. And how she bitterly regretted the words she had flung at him so carelessly, so thoughtlessly.

‘Rick didn’t tell you about a job, then?’ she asked Martin now.

‘Nah.’ He smiled at her. ‘He didn’t say anything.’ He stroked Ethel, who snuggled up even closer to him.

‘But it was after he spoke to them that he disappeared?’

‘Well, couldn’t rightly say the two things were, like, connected, but—’ Another shrug of his shoulders.

Cora wanted to know. She wanted to know right now whether the two things were connected, who the men were, what they had wanted with Rick. Whether he had done something really stupid.

‘They haven’t spoken to you then, Martin? These men?’

‘No, I ain’t seen them. Rick told me to be careful of ’em though. Come to think of it—’

‘What?’

‘Nobby said he’d been spoke to by some blokes.’ He sniffed, hard. Ethel moved away for a moment, then came back to his side.

‘Nobby?’

‘Yeah. He used to hang out in the doorway of the old bank. Said it was the nearest he’d ever get to any moolah.’

‘Okay.’ Cora tried not to show her impatience.

‘I haven’t seen him for a while. Or Lindy.’

‘Lindy?’

‘Lives in the grounds of St Peter Mancroft. By the hedge.’

‘Thanks, I’ll go and check it out.’

Cora could see Martin’s eyes beginning to close. ‘Martin, how about a night in the shelter?’ she said softly, reaching into her pocket for a biscuit for Ethel, who took it from her with careful teeth and a fair amount of slobber.

‘Nah. Thanks, Cora.’

She put her umbrella down by his side.

CHAPTER TWO (#u85a50a7e-2e82-5807-9488-b976b23d5c46)

DAY ONE: EVENING (#u85a50a7e-2e82-5807-9488-b976b23d5c46)

He was shivering, his teeth chattering, water dripping off his hair as he crawled out of the river and onto the shingle. The tee-shirt and boxer shorts he was wearing were sodden, clinging to his skin. He paused on his hands and knees, panting, exhausted, and looked around. There were lights in the distance, but not at this point of the harbour. Not here. Surely no one would have seen him?

The night was dark, there was neither moon nor stars, for which he was grateful. Less chance of being spotted.

Had he been missed yet?

He couldn’t stay here. He had to get moving. Get up. Get up.

His body was too heavy. He tried to unfurl, to stand.

So much effort.

He could do this. He’d been fit once. Muscle memory, that’s what he needed.

He gritted his teeth.

His head was pounding, there was a sickness in his stomach. He mustn’t think of what he’d had to leave behind. All that work, all those chances he’d taken and he’d had to get rid of it when he realized they were on to him. When he knew he had to escape. Right away. And he’d left her behind too. He’d wanted her to go with him, but she wouldn’t. Said she would slow him down. She would have done, and they could have made it together. Until it was too late for her.

Come on, come on.

Almost up. He stayed for a minute, back hunched, hands on the top of his knees, still shivering, always shivering. He couldn’t remember when he’d last felt warm, when his head was clear, when he felt well. He couldn’t remember.

A car. He needed a car.

Shapes grew out of the shadows. A shed, boathouses made of timber, two fishing boats resting on the concrete. The smell of fish and diesel in the swirling air.

He listened.

All he heard was the wind whistling around the edges of the buildings, then he became aware of the wind drying his body, his clothes, making him shiver more deeply, right down to his bones, to the damaged organs in his body.

Cold.

Cold was a killer.

He took a deep breath and staggered towards an old shed. Hugging its perimeter, he peered around the corner.

Nothing. Nobody.

Lights, though. On the car park. Not many, but enough. Had to keep away from those.

He set off in a crab-like run, fear giving an edge to his strides. He was better now, had to be better, had to get to freedom, had to leave this place behind.

He risked a glance over his shoulder, back at the island. Lights twinkled in the distance, making the buildings look benign. There were no signs that someone – him – had escaped. No floodlights, no shouting. But then there wouldn’t have been, would there? Too risky, even for them. He tried to listen, to see if he could hear the sound of a boat, a speedboat perhaps, coming to find him.

Nothing, even the wind had stopped its moaning.

Either he hadn’t been missed or—

The alternative was too awful to contemplate. He couldn’t have come this far for them to be waiting for him, just around some corner.

He ran. Past houses towards the road. Down the road. And there. An explosion of relief. Lights. A pub. Perhaps he could get a car. Out here, in the country, they could be careless with their security. He began to pray he was right as his breaths became ever more shallow, the kicking he’d received in his ribs making itself known.

There were cars in the car park. Swish cars, nothing old, nothing he could hot-wire. Frantic, breath coming too hard now, he looked around. A BMW. A Mazda. A Land Rover. A couple of Fords. Which one? Which one?

He limped over to the Land Rover, his muscles seizing up more with every step.

It was dirty, mud-splattered. The windows were open halfway. He peered inside. The floor was littered with empty sandwich packets, beer cans, tissues. There was an old, hairy blanket on the passenger seat. It smelled of damp and dog.

He pulled on the driver’s door. His hand bloody hurt. It opened. He leaned across and pulled down the sun visor. A bunch of keys fell onto the floor. He thanked fuck country people were so trusting.

As he jammed the key into the ignition, something made him stop. Listen. He clamped his lips together so he wasn’t hearing the chattering of his teeth. He slowed his breathing, told himself to be calm. There it was. A faint sound. Was it a motorboat? Coming from the island perhaps? His heart began to jump in his chest, and he turned the key in the ignition.

A noise like a giant clearing his throat came from the engine.

He turned the key again – so hard it could have broken off.

The engine turned over once, twice.

Cold sweat was dripping into his eyes.

It fired. He said a thank you to a god he hadn’t believed in for a very long time.

Without waiting to listen, or even to look to see if anyone was coming for him, he released the handbrake and pushed his foot hard on the accelerator.

He hadn’t turned the lights on, and the corner came up too quickly. He turned, hard. Made it round on two wheels, tyres screeching. The Land Rover bounced back onto four, he was thrown out of his seat, then back down. He breathed again.

Where were the lights? Where were the fucking lights? It was so dark. No moon. No stars. No street lights. No more comforting lights from the pub.

He looked down for a likely looking switch.

Where the fuck was it? Where the—

There. Light.

He looked up to see a pair of eyes in front of the windscreen reflected in the headlights.

He screamed and slammed on the brake, wrenched the steering wheel first one way, then the other.

The Land Rover lurched across the road, hitting the hedge on one side. Somewhere in his subconscious he heard the side of the vehicle being scratched by thorns, twigs, branches. Then, before he could think any more, the Land Rover was thrust, skidding, to the other side of the road.

A tree loomed in front of him. Once more he hit the brake.

He felt himself being propelled forward. Tried to throw himself across the seats. Slammed into the dashboard. His head thrown backwards then forwards. He was weightless. Felt a shower of glass. Time stretched, contracted, stretched again. Something trickled down the side of his face and into the corner of his mouth.

Rick’s last thought was of his sister.

The deer, unharmed, trotted off into the forest.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_29878b46-628d-5b45-968f-04d619a2375d)

DAY ONE: EVENING (#ulink_c836a37a-4491-5197-a73c-2508552f9ec8)

The sky was alive with a shower of red and green and yellow sparks as one rocket after another exploded in the night air. Beyond the lake, Catherine wheels crackled and whistled and Roman candles fizzed and hummed. Watching from behind the French windows, men and women in party clothes holding champagne glasses oo-ed and ah-ed their appreciation, grateful the wind had died down so they could enjoy the display. Alex Devlin sipped her warm tap water and wished she was at home, tucked up in bed with her hot water bottle.

‘Enjoying the fireworks?’

Alex turned to see a man looking down at her, a smile on his face. Mid-forties, she reckoned, swept-back black hair with wings of grey. Soft crow’s feet at the corners of his eyes. Laughter lines by his mouth. Could be anger lines, of course. All this she registered in a couple of seconds.

‘They’re very impressive,’ she said, carefully.

He raised an eyebrow. ‘Hmm. Does that mean “impressive but a waste of money”?’

A smile tugged at the corners of Alex’s mouth. ‘You may say that, I couldn’t possibly comment.’ She turned back to watch more of the display. More rockets exploding in the air. She could feel the man’s eyes on her.

‘I saw you earlier. With someone. It looked as though you were having an argument.’

‘Really?’ She wasn’t sure how to react. She wanted to ask why he was watching her and what business it was of his, but she didn’t.

‘I know it’s none of my business …’

Ah.

‘But I was watching you …’

Right.

‘Only because I was worried …’

Of course you were.

‘Worried?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t like to see couples arguing. It can lead to all sorts of things.’

‘“All sorts of things”?’

‘I’m sorry. I’m digging myself into a hole, aren’t I?’ He smiled wryly.

Alex laughed, the tension slipping from her shoulders. ‘Just a bit.’

‘Tell me.’

‘What?’

‘About the man you were arguing with.’

‘Why?’

‘So I know who I’m competing with.’

‘“Competing with”?’ Alex still tried not to smile. The arrogance of the man. She turned to look at him properly. Beautifully cut suit, blue tie, blue handkerchief poking out from the breast pocket, but yes, grey eyes. Wolfish.

‘Drink?’

‘Drink?’ She was confused at the sudden change of subject.

He nodded to her empty glass. ‘More champagne?’

‘I’m drinking water.’

‘Are you sure I can’t tempt you? You look as though you might need a glass.’

‘Really?’ She didn’t look that shaken, surely. Still, she did feel as though she could do with some alcohol at this particular moment. Sod it. ‘Okay. Why not?’ Now she did allow herself to smile fully at him.

He clicked his fingers and a woman, impeccably dressed in a white shirt and tight black skirt, glided towards them, bearing a tray at shoulder height. Alex wasn’t sure whether she was supposed to be impressed or not. She wasn’t. In fact, after the evening she’d had, it would take more than an imperious clicking of fingers and a solemn waitress bearing booze to impress.

The woman handed her a glass; Alex drank deeply, hardly appreciating its coldness and the pop of bubbles on her tongue.

‘Looks like you needed that,’ he said.

‘I did. Thank you.’ She took a more delicate sip, wanting to savour it this time.

‘Who was he?’ The man leaned against the window. The fireworks had ended.

Alex sighed. ‘He was a friend who wanted to be more than a friend.’

He was David Gordon, the head of a charity for the homeless in East Anglia, who had invited her along to the event at Riders’ Farm – an event not in aid of his charity, but for one concerned with refugees. He liked to pick up ideas, he told her. Also, he said, the Riders were big donors to Fight for the Homeless and it behoved him to be there. Alex thought at the time his use of the word ‘behoved’ was rather sweet and old-fashioned.

She had found David an interesting person to interview for The Post. He had come into money and had decided to put it to good use. He wanted to make the lives of homeless people more normal, he had told her earnestly. To fight the root causes of homelessness. It was no good merely giving money to beggars on the street, you had to put that money to good use. To fight drugs, robber landlords, the benefits system. And to that end he had set up a hostel in Norwich and another in Ipswich where people could go and not have to account for themselves in any way, but would be helped with whatever problem they had. No one would ask them questions.

Finding out about David’s hopes and ambitions had been the sort of freelance job she liked best. A good subject, an interesting cause. She’d enjoyed herself, so when he’d asked her to join him at the function at the Riders’ farm, she’d agreed. She’d heard that the event at the rather splendid farm was the place to be seen. Not that she was interested in being seen as such, but there could be some people here who would make good subjects for future features she enjoyed writing. And she might even get a news story of some sort out of it. She badly wanted to up her news credibility with Heath Maitland, the news editor at The Post.

The evening had started off so well, with David taking her to a delicious early supper at the nearby Dog and Partridge.

The party was well underway by the time they arrived at Riders’ Farm. Alex could hear the strains of a jazz band as they walked towards the large oak front door up the path lit by dozens of bamboo garden torches and strings of fairy lights hanging from the bare branches of trees.

At first David had been the very model of attentiveness, making his way through the packed rooms, introducing her to all sorts of people from the chief executive of a local hospice to the raddled drummer of a famous band of old rockers. The great and the good were in evidence everywhere. Suffolk’s Assistant Chief Constable was chatting to a prominent surgeon from Ipswich Hospital. The Chief Fire Officer was listening to the Lord-Lieutenant of Suffolk – a post currently held by a countess. And the canapés were delicious and the champagne cold.

‘When do I get to meet the Riders?’ Alex asked, after spending several minutes in the company of the pompous High Sheriff of Suffolk, complete with the gold medallions of office, who was telling her how the city council was about to adopt a zero-tolerance policy towards beggars on the streets.

She couldn’t wait to get away.

‘There’s Marianne, the matriarch, I guess you’d call her.’ David nodded across the room.

Marianne Rider was tall and elegant, wearing a crimson dress that was nipped in at the waist and fell to the floor. Her silver hair was carefully twisted in a chignon and diamonds glinted in her ears. As if she knew she was being looked at, Marianne Rider turned and stared at Alex. The woman’s face was tastefully wrinkled, though the number of lines around her mouth denoted a heavy smoker. Her lipstick matched her dress. A silver necklace glinted across her collarbone. She didn’t smile. She turned back to continue talking to the man next to her.

Alex almost shivered. She felt snubbed. Marianne Rider did not look a cosy sort of person.

‘And that’s her husband next to her, Joe Rider,’ said David.

Joe Rider was as tall as his wife and stood dutifully nodding at whatever she was saying while sipping from a glass. His dark navy suit was stretched across his paunch. He was sweating slightly, and he ran his fingers around the inside of his collar as if it was restricting his breathing.

‘I can’t see the three sons, but they must be around somewhere,’ said David. ‘Apparently Marianne likes the family to present a united front, so they always have to come to these events with their wives.’

‘Wives? You make it sound as though they’ve got several each.’

David laughed. ‘One of the sons is on his third wife, but I don’t think all three have to attend. Still, I’ll introduce you when I see them.’ He tried to sound casual, but Alex could hear the excitement in his voice. She didn’t like to tell him that she had done a bit of research before the evening and knew a little about the Riders. They were an old farming family who owned a lot of land in Suffolk, an awful lot of land, including an island off the coast. An island about which there were all sorts of stories, stories of strange lights and noises at night. Screams carrying over cold air. Bodies washed up on beaches. Local people said the island was haunted.

‘… diversification. Are you listening to me, Alex?’ David stared at her with irritation.

‘Sorry.’ She tried to look contrite.

‘What I was saying was that they have diversified and done very well out of it. They have “forest lodges for the backwoodsman” on some of their land.’

‘For townies to “experience” the countryside, I suppose,’ said Alex, grinning. ‘Yes, I read about that.’

‘There’s also a centre for holistic therapy, complete with yurts, and a couple of barns that can be used for corporate events or as wedding venues. Of the three sons, Simon, the youngest, is married, and has a degree in chemistry or something. The eldest, Lewis, is on his third wife as I said, and the middle son, Jamie, has just got divorced. There we are. A potted history.’

Alex wondered if she was meant to give him a round of applause.

The evening continued. Alex was now drinking water, much to David’s annoyance.

‘I need to keep a clear head, David,’ she told him more than once. ‘I’ve got to do an interview in the morning.’

‘But you shouldn’t waste all this,’ he said, sweeping his arm around the room.

‘I’m not, I’m enjoying talking to people.’ Some, anyway.

‘But—’

It was almost as if David wanted to get her drunk.

And just before the fireworks started he had manoeuvred her into the cold air of the garden for ‘a walk to clear their heads’.

‘My head is perfectly clear, thanks, David.’

‘Come on, don’t be a spoilsport.’

He was beginning to get a little bit annoying. She took a deep breath, she really didn’t want to ruin the evening. ‘What do you mean? I’m not a spoilsport, and anyway, it’s bloody cold out here.’ She rubbed her arms, trying to get rid of goosebumps. She tried to smile at him. ‘Come on, let’s go back into the warm.’ There was something about the way David was looking at her that was making her nervous.

He lunged towards her.

Startled, Alex jerked her head back. David stumbled, and she tried – and failed – to suppress a giggle. Then she saw his face: puce and furious.

‘David, I—’ she said, searching frantically for words to let him down gently, knowing her laugh had been cruel.

He grabbed her shoulders, pulling her towards him and managing to plant a wet kiss on her mouth.

‘No, David.’ She wriggled out of his grip, resisting the desire to wipe the back of her hand across her lips.

‘Why not? Aren’t I good enough for you?’ He flushed, his lips wet and flabby.

‘Don’t be silly. I see you as a friend, that’s all.’ She tried a smile. ‘I’m not looking for a relationship right now.’

‘With me?’

‘With anyone. I am sorry, David.’

‘You led me on.’ His face was suffused with anger, the veins in his neck like cords of rope.

Alex was taken aback. ‘I don’t think so.’

‘You did.’ He thrust his chin forward, hands in fists.

Had she? Not to her knowledge. ‘David—’

‘Oh, forget it, you’re just like all the others.’ He marched off, leaving Alex even more confused. That had come out of absolutely bloody nowhere and there was no way she had ‘led him on’, as he put it. She really didn’t have any desire for a relationship at the moment. She’d been there, tried that.

‘It was David Gordon, wasn’t it?’

The man’s voice brought her back to the present.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Fight for the Homeless charity?’

‘You were spying on me,’ she said mildly. ‘David and I were outside when we argued.’

The man threw back his head and laughed. ‘Caught. I promise I wasn’t being pervy, I was merely looking out of the window when I saw the pair of you.’ He shook his head. ‘Arguing. Is that what you call it nowadays. Poor David. Never has much luck.’

‘I don’t think luck comes into it. I hadn’t encouraged him at all when he—’ She stopped. What was she doing explaining herself to a stranger? He had no right to know anything about her. She was irritated with herself. She put her glass down on a tray being carried by a passing waiter. ‘If you’ll excuse me, I must leave.’

He put a restraining hand on her arm. ‘Wait. Do you have to?’

‘Yes. I have to be up in the morning for a radio interview.’ She looked at his hand. He let it drop.

‘How intriguing.’

‘Not really.’ She gave him a brief smile as she turned to go.

‘Stay.’

She looked at him. ‘I really do have to get home.’

‘I’m Jamie Rider,’ he said as if she hadn’t spoken. He put out his hand.

Alex took it. She had known it was Jamie Rider, although he was far more impressive in real life than the photos she had found of him had led her to believe.

‘Alex Devlin,’ she said, shaking his hand.

His grip was warm and firm. ‘The journalist.’

‘Oh dear. You said it like it was a cross I had to bear.’ She laughed, lightly.

He laughed. ‘Not at all. Your book is like a bible for my mother.’

She gave a wry smile. The book. All the profiles she had put together about interesting people, the stories she had written about the danger of suicide forums on the Internet, the investigations she had done into dodgy business practices, all this counted for nothing against a book she had been commissioned to write after an article of hers had appeared in the paper about extreme couponing. The art of collecting coupons and vouchers and spending them well was a very popular subject. Popular enough to write a book about and for the book to get onto the bestseller lists. Popular enough to give her the cash to put a deposit down on a waterfront apartment in Woodbridge.

‘That’s good to hear,’ she said, thinking he was either having her on or was trying to ingratiate himself with her. After all, what possible pleasure would the imposing and somewhat terrifying Marianne Rider take in cutting out coupons from newspapers? It didn’t go with the red dress and frosty look.

‘Perhaps you could sign it for her some time?’

‘Of course.’ Really? she thought. ‘And you. What’s your niche on the farm? The backwoodsman lodges, the yurts or the haunted island?’

Jamie Rider threw back his head and laughed. ‘You make us sound like a family of weirdos.’

Alex raised an eyebrow.

‘Ah. You think we are a family of weirdos.’ He nodded. ‘Fair enough. But I don’t have anything to do with any of those projects. Never have. I’m far too boring. I work in the city.’

‘Banking,’ said Alex.

‘You’ve been doing your research. I’m impressed.’ He didn’t look impressed. ‘Yes, banking. Very dull.’

‘Not at all,’ she replied, trying to sound politely convincing. ‘I’m sure it has its own delights.’

Again he laughed, and Alex found she enjoyed hearing it. It made her smile. ‘But now,’ she looked at her watch, ‘I really must be going.’

‘No. The night is still young.’ He frowned. ‘You can’t disappear like some sort of Cinderella, not when I’ve just found you.’

‘I have been here all the time, and I’m afraid I must disappear. So, please excuse me.’

‘Can I give you a lift? I mean, since you and David …’

She shook her head. ‘I’ll be fine, thank you.’

‘But the roads.’

‘I know the roads. And maybe I brought my car.’

‘Maybe you did, but you have been downing the champagne. And, if – as I imagine you did – you came as David Gordon’s guest, then you will have lost that lift home.’

‘Not necessarily. I’m sure he would take me home if I asked.’ Actually, she was bloody sure he wouldn’t. ‘In any case, the fresh air will do me good.’ She was enjoying the banter but she really did want to get home to her bed so she was fresh for the radio interview in the morning. Besides, she didn’t want or need any complications in her life, and Jamie Rider looked as though he could be a very big complication, if she let him in. No, she would go outside and order a taxi.

‘Fair enough,’ he said. ‘Maybe I could see you another time? Show you around the farm? Book you in to realign your chakra?’

‘Maybe.’ She smiled, graciously, she hoped.

Chakra indeed. It really was time to leave.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_45323048-14d0-5cbc-8d32-00f07f9ec10f)

DAY ONE: LATE EVENING (#ulink_3438f0c0-8234-5e6b-bf53-f4ff721b1847)

Cora didn’t see the two men until it was too late.

Normally, she would catch the last bus home after an evening shift at the hospital, but tonight she had worked late thanks to an emergency admission and so she’d missed it, but a colleague gave her a lift part of the way, dropping her on Unthank Road – not too far for her to walk. However, this was Norwich, and there weren’t many people out late at night in that part of the city, which was well away from the nightclubs and the pubs the students frequented, so she hurried along, trying to make herself as inconspicuous as possible. Once or twice the hairs stood up on the back of her neck and she looked over her shoulder, convinced she was being followed, but she saw nobody.

She decided to take a shortcut through Chapelfield Gardens that was lit in part by sickly yellow sodium lights. A couple meandered along in front of her, hand-in-hand. She passed a group of four men, swaying with booze. They called out to her; she ignored them.

Two men stepped out of the dark in front of her. She stopped, smiled.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, pleasantly, hoping they would stand aside.

They didn’t.

‘Excuse me,’ she said, more loudly now, her heart fluttering in her chest. This was not a good situation. Still they didn’t move. She glanced around, wondering if she could shout for help, but the gardens were now empty. The two men moved smoothly to flank her either side, pressing her between their bodies. Both were much taller than she was.

‘Cora,’ one of them said without looking at her, ‘you shouldn’t be walking around on your own.’

‘Especially not here,’ said the other. ‘In a deserted park an’ all.’

‘Have you been following me?’ Her mouth was dry. Fuck it, she’d been right.

Man Number One, who was thickset with rubbery lips, smiled at her. ‘Since you left the hospital,’ he said, cheerfully. ‘We’d been waiting for you to leave. Though you didn’t make it easy, missing your bus and everything. Good job we had our car parked nearby. Especially as parking can be hell at NHS places, don’t you find?’

‘I don’t know who you are,’ Cora said, keeping her voice low and even as if she were talking to a frightened child, ‘but I would advise you to get out of my way.’

‘Or what, Cora?’

His lips were wet with saliva; it was all Cora could do not to shiver.

Then the two men began to hustle her along the path so fast that her feet were barely touching the ground. Her heart began to beat even faster.

‘What are you doing?’ She tried to wriggle free, but the two men merely gripped one of her arms each and carried on walking. All she could hope for was that they would pass someone and she could shout for help.

The group of drunks. There they were, ahead of her.

‘Help,’ she shouted, though it came out more like a whisper.

She gathered her breath, opened her mouth. One of the men punched her in the stomach. She bent over, winded.

‘All right, mate?’ she heard one of the drunks say as they hurried by.

‘All right,’ said Man Number One. ‘A few too many. Y’know.’ He laughed.

‘Fuckin’ do,’ said the drunk. They all laughed. Cora was still trying to catch her breath.

‘Look, Cora love,’ said the skinny man on her left, as they turned out of the gardens and began to walk down the road. ‘We don’t mean you no harm. Not intentionally, anyway. This is just a little warning.’

‘A warning, that’s right,’ said Man Number One, squeezing her shoulder hard. ‘Stop poking around, asking questions.’

‘Yeah, poking your nose in where it’s not wanted.’

‘Looking for Rick, you mean?’ she said through gritted teeth. Her stomach hurt. ‘Is that what it’s about?’ It was all she could think of.

‘Yeah.’

‘Why?’

‘Why what?’

‘Why shouldn’t I look for Rick?’

‘It’s not just that. Boss reckons you interfere too much and people’ll start talking.’

‘Listening, you mean.’ Anger made her bold. ‘They might just start listening.’ She tried to shake them off, but they held on even tighter. Rain had begun to fall.

‘Whatever.’

‘Who’s your boss? One of the Riders? Which one?’

Her question was met with laughter. She knew she was right.

They were now in an alleyway at the back of a row of shops – Topshop, she thought. MacDonald’s. No one to hear her.

‘Boss knows you like chatting to the homeless,’ said Skinny Man, dragging her towards one of the large grey industrial wheelie bins, ‘so we thought you could spend a bit of time being in their gaff.’

Okay, she thought, so they were going to dump her in a bin to make a point. To frighten her. And they’d done that all right. She was frightened. And getting cold from the rain. But at least she could climb out of the bin when the men had gone.

All at once Man Number One grabbed her arms and jerked them behind her back, wrapping gaffer tape around her wrists. Before she could scream, Skinny Man had slapped tape over her mouth, wrapping more tape around her head. Fear coiled in her stomach. Man Number One pushed her and she fell heavily on to the ground, banging her head on the hard concrete. Her vision went black for a moment and she felt sick. Then more tape was wrapped around her legs from her knees to her ankles, before she heard one of them push open the lid of the wheelie bin, and then she was tossed inside like a piece of rubbish.

‘Take this as a warning,’ Skinny Man said, smiling down at her.

The lid slammed shut.

The smell hit her first. The sweet tang of rotting food. Fried onions. Mouldy old rags. Body odour – from old clothes? Chips. The sourness of beer. There would be maggots, she knew there would be maggots. Fat. Crawling. Wriggling. She was lying on cans. Bottles. Cardboard containers. Lying on all sorts of rubbish. Slime. In the dark. Terror rose in her throat. Bile too. No, she must not be sick. Not be sick.

Another thought: would the bin be emptied tonight? Her terror grew so it was almost uncontainable. She could scarcely breathe. She had heard about this. Knew it had happened to homeless people, or drunks who thought they’d found somewhere safe for the night. And then the bin lorry came along, scooped up the bin and emptied it into the lorry where the contents were crushed before being taken to the landfill site. Her body would never be found. She would never be able to help Rick. To bring those who deserved it to justice.

Oh, Rick, where are you?

She tried to throw herself against the side of the bin – for what? To topple it? To make a noise? No matter, however many times she tried, nothing happened. It didn’t move. No one heard her. She tried to stand up, but kept sinking down into the rubbish. She screamed, but the tape muffled her cries. It was dark. It stank. She was wet. Cold. Her throat hurt. There was no air. No air. She closed her eyes.

She had no idea how long she had been lying in the bin, but now she heard it, the noise of a lorry on the street nearby. Could it be the bin lorry coming to collect the rubbish? To collect her?

Fear made her freeze.

Light. Not light, but not dark either. Fresh air. Rain on her face.

‘Here let me help you.’

Someone – a man – leaning right over the edge of the bin, holding out his hands. She tried to shuffle towards him, carefully, so she wouldn’t sink any further into the filth. He grabbed her under her arms and hauled her up and over the lip of the bin. Her shoulders burned. For the second time that night, she landed on the hard concrete.

The man jumped down off the pile of crates he’d been balancing on, and bent to tear the tape off her head and mouth.

It hurt like hell.

He produced a knife and cut her wrists and calves free.

‘Come on. Leg it.’

A bin lorry came around the corner.

Cora held on to the man’s hand and legged it.

Chapelfield Gardens again. Cora sat down on a bench.

Her rescuer wrinkled his noise. ‘You stink.’

Cora looked at him, at his trousers held up by a tie, his stained knitted jumper underneath a buttonless coat out of which protruded much stuffing. ‘You can talk.’

Her rescuer grinned. ‘Maybe. Glad I got you before the crusher did.’

Cora nodded, then began to shiver. ‘How did you know I was there?’

Her rescuer shrugged. ‘A man gave me some dosh, told me where you were and told me to get you out. Preferably before the lorry.’

Now Cora laughed. ‘Thank you. Do you know who the man was?’

He shook his head, putting his finger to his lips. ‘Hush money, that’s what he said.’ And he ran off down the path.

Cora couldn’t stop shivering.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_d941f1a2-c570-5ce5-8fe4-5b7e10fecdd4)

DAY ONE: LATE EVENING (#ulink_9e024e9b-416e-5bad-b45b-bbaa66de00e0)

Alex hunched into her coat and pushed one hand as far down into a pocket as she could. The other held her phone with the torch light on so she could see her way. The weather had turned from clearsky cold to stormy in the time she had been at the charity event. If she looked at the ground, the wind wouldn’t whip across her skin. The stars were hiding behind furiously dark clouds.

It hadn’t been her greatest idea. To attempt to order a taxi to come to the middle of nowhere on a weekday night. Or any night, thinking about it. It wasn’t as if she could call an Uber, or that there was a plethora of taxi firms in the area. The two firms that did answer her call said they were too busy. Alex imagined them shaking their heads ruefully as they put the phone down.

Why hadn’t she ordered one earlier?

Because she hadn’t realized she would need one.

So she began to walk, reasoning that it wasn’t too far to Woodbridge. And when she got a decent signal again, she would give one of the taxi firms who hadn’t picked up another try. Or, when she reached the Dog and Partridge, where she’d had supper with David, she might be able to persuade the owner’s student son to take her home for a bit of cash.

On reflection, perhaps she should have let Jamie Rider drive her home. Still, she’d had a lucky escape from David. Where had that mauling come from? She hadn’t encouraged him; there was no way she was even interested in him. Or anyone, for that matter, especially now her life was coming together at last. She didn’t feel as though she was being buffeted by the winds of chance any more and was finally feeling at peace with herself. The guilt that had weighed so heavily on her for years had lifted. She had a new start. Finally, she knew she deserved it.

All she needed now was a juicy story to get her teeth into. It was all very well having a bestselling book – and she wasn’t complaining, it had bought her independence as well as the new flat – but she did want to be taken seriously. She’d been writing features for The Post for a long time now. She wanted something else, something worth doing. She’d had a taste of it eighteen months ago when she was delving into the proliferation of suicide forums on the Internet and the financial shenanigans of the previous editor and owner of the newspaper. She’d enjoyed writing that copy.

The rain began to fall, gently at first, then it came on harder, running icily down the back of her neck. Damn. She was going to get properly wet now. And cold. She tried to protect her phone. It would be the last straw if that was ruined. And her feet were hurting. Those damn heels. Why hadn’t she brought flat pumps to change into? Because she hadn’t thought she was going to have to walk home, had she?

She had talked to Heath about more work, about her desire to be taken more seriously. Heath, whose looks, charm and inherited wealth belied a sharp operator, was the owner of The Post as well as its news editor. He wanted to be hands-on, he’d told Alex during one of her rare visits to London. She had told him she wanted more excitement in her working life. He’d stretched out his long legs, pushed his floppy fringe out of his eyes and said, ‘Well, you don’t want a staff job on The Post, I know that. Don’t sit around moaning, Alex. You’re a freelance, a self-starter, even if you do have enough money at the moment. It might not always be like that. You call yourself an investigative journalist, so get out there and find something to investigate.’

Tough love.

For a few days she’d been hurt, resentful, but she knew he was right – damn him. It was up to her to find stories, to get stuck into something.

Her phone buzzed. She peered at the screen. Her sister. Her heart used to sink when she got a call from her, but now it was like being phoned by someone – ordinary, was that the word? Probably not. Normal? What was normal these days? What she meant was that she didn’t go into worry mode as soon as her sister’s name cropped up on her phone. Or in conversation.

‘Hey, how’re you doing, Sasha? It’s a bit late.’

Though she knew her sister didn’t sleep much, not these days. She might be stable, her mental health issues on an even keel, but sleep was the one thing that eluded her. Too many thoughts in her head, she’d told Alex. Too many regrets.

‘Alex, guess what?’ Her sister was bubbling with excitement. No preamble. ‘There are critics coming up from London for my exhibition. Real-life critics want to view my paintings. Mine! What if they don’t like them? They might hate them. You will be at the preview, won’t you? You will be there?’ Her words came rushing out, tumbling over each other.

‘Whoa, slow down, Sasha,’ said Alex, smiling at the sheer joy in her sister’s voice. ‘Of course I’ll be there. It’s at that swish gallery in Gisford, isn’t it? I’m not far from it now, actually.’

‘Really? Is that where the charity do was then?’

‘Nearby. A big farm. Big landowners. Pots of money.’

‘I know the ones. Pierre told me about them.’

‘Pierre?’ Alex grinned even though Sasha couldn’t see her.

‘The gallery owner. And not my type. So, you know where it is, there is no excuse for you to miss it.’

‘I wouldn’t miss it for the world. The date’s in my diary.’

‘I’m so glad you’ll be there. It wouldn’t be the same without you. Can you believe it? Extremely famous people have exhibited there and now me. Me. I hope Mum’ll come too.’

‘You deserve it, Sasha. You’ve worked hard.’

‘So how was the charity gig? You were going with that bland bloke, weren’t you?’

‘David. And he’s not bland. His work is very interesting,’ she replied, tartly.

‘So how was David?’ Her sister was teasing her.

‘The do was a bit dull, in all honesty. And David was, well, not for me, shall we say.’

‘Do I detect something not right, my darling sister?’ There was amusement in Sasha’s voice, and it gave Alex such pleasure to hear it. For years her sister had been so very fragile, doubled under the weight of guilt from which Alex thought she would never recover. But she had, as journalists such as herself were fond of saying, ‘turned her life around’, and was making a pretty good success of her art – something she had started as a hobby only relatively recently, but a hobby that had turned into a passion, and a passion that was quickly becoming a career.

‘Put it this way—’ Alex began, but then her words were interrupted by a beeping sound. Damn. The phone battery must be low. ‘He was persistent.’

‘And?’

Beep. She knew she should have charged her phone before she left home.

‘And, nothing.’ Alex suppressed a shudder as she saw in her mind’s eye those wobbly lips coming towards hers. ‘He’s not my type,’ she said, briskly. ‘Worthy and all that, but not my cup of tea.’

Beep.

‘So you won’t be bringing him to my preview?’

‘No.’

‘That was pretty definite. Anyway, I must go. Art to create and all that. See you.’

‘Sash, hold on—’

But her sister had gone. Damn. She’d been about to ask her to phone a mate to come and fetch her.

Beep.

And that was it. The battery was dead.

‘Bloody hell,’ she muttered, shaking it as if that would bring it back to life. ‘Stupid, stupid woman.’

Definitely dead. No chance to ring Sasha or anybody else now.

She looked up. The light was fading fast. The wind was even sharper now, and the rain like needles on her face. There was a slight ache behind her temples. She didn’t think champagne was meant to give you a hangover. And she had drunk plenty of water. She bent her head lower and trudged on, regretting once more declining that offer of a lift. Her hands were numb, even inside her gloves.

All at once she became aware of a flickering orange light in her peripheral vision. Was she imagining it? Was her brain more alcohol-fuddled than she realized? On. Off. On. Off. She began to walk more quickly.

There. She peered down and could just about make out marks on the road. Skid marks?

She stumbled on.

Then, around a corner and out of the dark loomed a vehicle on its side in the ditch with an indicator light flashing lazily. She hurried towards it.

Judging by the tyre marks and the torn vegetation the Land Rover – for she could see it was that – had lurched from one side over to the other, then hit a tree before coming to rest in the ditch.

The front of the vehicle had caved in and the windscreen had been smashed to smithereens. Glass littered the road and the verge. A strong smell of petrol made her head hurt even more. Christ. Gingerly, she made her way over to the open driver’s door. No one inside. She looked in the back. Nothing. Then she heard a groan coming from a few feet away.

A man was lying on the ground like a ragdoll, his clothes half-flayed off him, his face a bloody mess. He groaned again. Rain diluted the blood that ran off him in rivulets. She hoped he looked worse than he was.

She knelt beside him and took his hand, swallowing hard. ‘It’s going to be okay. I’m here. You’re going to be all right.’ Her tears welled up at the lie.

‘Cold.’

Alex shrugged off her coat and laid it on top of him. ‘There. Now look, I’ve got to leave you.’ She peered into the unyielding darkness, wondering where the nearest house was. She thought she wasn’t too far from the pub, but how far? What did she reckon? The darkness was oppressive, and she had lost her bearings. The pub could be around the corner or a mile away.

‘No.’ A hand gripped her wrist strongly. ‘Don’t leave.’

She put her hand over his. ‘I’ve got to. I’ve got no battery on my phone, I can’t even make an emergency call. I need to fetch help. Do you understand?’

‘Yes. Don’t go. They’ll come. Here,’ she felt him press something in her hand, ‘take this. My sister—’

‘Please. Don’t talk.’ Her voice sounded desperate and she knew it. She was desperate. She had to get help – he was in a bad way.

She crumpled the piece of paper in her hand while trying to tuck her coat around him, oblivious to the fact that she was becoming soaked through. His skin was clammy. His breathing was becoming laboured. She could hardly bear to look at his poor, bloody face, but she made herself, and there was a flicker of recognition in her brain. He was wearing a gold chain. That, like his face, was familiar. She’d seen this man somewhere before, she was sure of it.

Before she could process the thought, she heard the sound of a car coming fast along the road. Thank God, thank God. ‘Help is coming,’ she whispered to the man.

His eyes opened. They were dark pools among the blood and torn skin.

‘It’s going to be okay, I promise.’

‘No,’ he said. His eyes closed. ‘It’s not.’

Alex leapt up as she saw headlights careering towards her and waved frantically. ‘Stop. Please stop.’

Two men jumped out of the car and hurried over to her.

‘You have to call the police. And an ambulance. There’s a man who’s been seriously hurt—’ Alex could hardly get the words out in her haste.

‘It’s all right,’ one of them said, turning the collar of the red Puffa jacket that strained against his body up against the rain and walking over to the injured man. ‘We’ve got this. We’ll take him to hospital.’

‘We shouldn’t move him.’ Alex was agitated. She wanted proper help. People in green with stethoscopes. The reassuring lights and sound of an ambulance. Her head throbbed.

The man shook his head. ‘Can’t call an ambulance. No signal.’

‘But—’ She was going to say she had been on the phone to her sister not long before, though she did know there could be a decent signal one moment and none the next in this part of the world.

‘If we don’t take him to hospital he might die anyway.’ The man in the too-tight jacket whipped her coat off the injured man. ‘This yours?’

Alex took it back and put it on over her wet clothes, then realized she was still clutching the bit of paper the injured man had given her. She shoved it into her pocket.

The two men heaved the injured man into the car, almost stuffing him onto the back seat. He groaned in pain.

No, this wasn’t right.

Alex had a half-memory from a First Aid course she had done years before that told her a casualty shouldn’t be moved if at all possible. But then, even if there was a phone signal, how long would it be before an ambulance came to this rural road? Perhaps the only answer was to let these two men take him to hospital.

‘Be careful, you’ll hurt him even more.’

‘Don’t worry.’ The second man turned to her. His dark wool coat was glistening with raindrops and he had an unmistakable air of authority. ‘We’ll get him to hospital.’

‘Which one?’

‘Which what?’ He shut the car door on the injured man as the man in the red Puffa went to the driver’s door.

‘Hospital. Oh never mind, just get him there, will you. And hurry, please.’

‘Don’t worry, we will.’

‘Hang on,’ she said. ‘Here.’ She delved into her bag and pulled out a business card. ‘Take this. Give the police my number. They’ll probably want to talk to me. And could you let me know—’

‘Police? Yes, of course. I’ll call them.’ He snatched the card from her hand. ‘We’d better get going.’ He jumped into the car and it drove off, wheels spinning on the tarmac.

Alex watched it go. Something didn’t feel right. But her head was fuzzy and she couldn’t grasp what was wrong.

The orange indicators of the crashed Land Rover continued to flash, and in the strobing light Alex saw a solitary trainer, soaking in a bloody puddle.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_d44b6ab6-f61f-5743-a2bd-4fe4c2c9b48d)

DAY ONE: LATE EVENING (#ulink_74352c78-85ba-5d75-9f03-40887658f6a8)

He was in a car, he could hear an engine, feel his body jar as it went over bumps.

What had happened to him?

A crash, that was it. Driving too fast. Something on the road. A deer? A deer on the road. Hit his head. Hard. Men came. How many? Two? Was there someone else there as well? Think, for fuck’s sake, think. It was all just out of reach. The men picked him up and tossed him in a car. He was hurting and he wanted to cry out, but he didn’t. Again, instinct kicked in. He played dead. Almost dead. He was in a bad place.

The car stopped. The two men in the front seemed to be arguing. Something about ‘cover it up’ and ‘as if it hadn’t happened’. What was that all about? One of them banged the steering wheel.

He tried to open one eye. Couldn’t. Stuck. Rubbed his hand over his eyes, Christ his hand was sore, then managed to open them, a little bit.

The men were getting out of the car. He strained to listen to their argument. He couldn’t make out any words, but he could smell salt, diesel. A port?

Wait a minute. The estuary again. They were going to take him back. Where to? He didn’t know, couldn’t remember, but he knew suddenly and with absolute certainty that if he went back he would never leave.

He emptied his mind of all extraneous thought and concentrated on moving his limbs. He ignored the pain that shot through his shoulder as he tried to open the car door as quietly as he could, praying they hadn’t put any internal locks on. The two men were still arguing.

He held his breath as the door opened. He rolled off the seat and onto hard concrete, jarring all the bones in his body that were already screaming with pain. He could hear the men’s argument more clearly now.

‘We keep quiet about this, right?’ The first man’s voice was gruff, slightly accented. Local? He wasn’t well enough versed in the Norfolk and Suffolk accents to be sure.

‘They’ll find out, you know that.’ Definitely Essex.

‘Look, we get him back, patch him up and he’ll be back at work in no time.’

Back at work. Flashes of memory. Taken underground. Kept underground. Packing boxes. Trying to talk to others who were doing the same thing. Learning they’d been taken. Taken? What did that mean?

Rick heard one of the men inhale deeply, then he saw a cigarette butt thrown onto the tarmac and ground underfoot.

Hurry, his brain screamed. Hurry.

Through sheer force of will, he made himself get onto his hands and knees – Christ, that hurt – and he started to crawl away. He glanced around, trying to take in his surroundings. There was no light from the moon or stars. As his eyes grew accustomed to the dark, he made out a few cars parked here and there, an unlit streetlamp. He had painfully made his way to one of the other cars. Now what?

He heard footsteps, running. Expletives, not shouted but spoken quietly, angrily. They were looking for him. He saw their shoes coming nearer to the car. They were going to find him. Then:

Laughter. Chatter. A group of people? The laughter died away. ‘Can we help you?’ a voice called. Friendly.

‘No.’ Rude. aggressive.

‘From round here, are you?’ The voice was less friendly.

Rick chanced a look around the back of the car. He saw the two men who had picked him up with their backs to him. They were facing a crowd of, what? Six, seven men? Maybe out of the pub, walking off the booze. The right side of aggression. For now.

‘Look,’ said the first man, the one in the smart coat, ‘we don’t want trouble.’

‘Nor do we,’ said the group’s spokesman. ‘Gisford is a quiet little village where nothing happens because we don’t want anything to happen and we always remember strangers.’

‘Okay, okay. We’re going.’

The men who were trying to take him somewhere he didn’t want to go – wherever that was –got into their car and drove off, fast. Where were they going? And how long before they came back looking for him? He didn’t have much time.

The laughing group wandered away, and Rick slowly came out from behind the car.

He was on some kind of harbour front. Concrete. The sea lapping at the edges. Across the water – the estuary he had swum across? – there were lights. Is that where he had come from? He had a bad feeling in his gut about the island across the water.

Keeping to the shadows, he limped away from the sea as fast as he could and towards a small road. It was dark, apart from the odd twinkle of light here and there from behind an upstairs window of a house. It was late then.

Better keep away from people. Vehicles. They might come back for him.

He set off down the narrow lane, looking for a gate or somewhere he could get off the road and hide. But there was nothing.

Then he heard an engine. A car. Had to be them.

He crouched down, then rolled under – thank fuck – a hedge, hardly daring to breathe.

The car went past him. Slowly.

He was comfortable here. Wanted to sleep. Only for a minute.

He closed his eyes.

Rick thought he remembered French doors opening out onto a stone-flagged patio. A small retaining brick wall. A table and chairs and parasol. Green parasol. Maybe grey. Did it matter?

It did.

His whole body ached.

He kept his eyes tightly closed, shutting out the cold and the dark, the sound of a tap dripping and the dank smell of rotting vegetation, and tried to feel the warmth of the sun on his head and the scent of newly mown grass in his nose.

He thought hard.

There was laughter, he was sure of that. A child’s voice, pure and high. His child? Sister? Brother? His head was so muddled. Had been for years. He shivered but felt the sweat roll down his back.

Wait.

Back to the sunshine.

A woman. Small. Blonde. Smiling at him. His wife. Her name? What was her goddam name? He wanted to cry out in frustration, but something told him to keep silent. Helen, that was it. But as soon as he thought of her name the dark began to roll in again. Why? What had he done?

Water. He’d swum across the estuary. Dark. Cold. He’d climbed into a car – hadn’t he? Yes, yes. He’d been on his own, though he’d wanted to take Lindy. But she didn’t make it. Why not? What happened? Was she here?

And who was Lindy?

The blonde woman? No. She was definitely Helen. Don’t think about Helen.

And he’d left something behind, something important.

He shivered. And realized his body was a mass of aches and pains. He ran his tongue around his mouth and felt a couple of loose teeth. Tried to lift his head.

Fuck that hurt.

He gritted his teeth. Lifted his head again. Let it fall back. Too much pain.

Where was he? It wasn’t hot enough to be the desert, not cold enough to be Norway or Russia, so where the hell was he?

He could do this, he’d been trained to withstand all sorts. He’d been trained by the—

What was he thinking? That he’d been trained by the army. Fuck, yes. Heat. Desert. The girl with the almond eyes. Push them away.

Army. That’s who he was.

He opened his eyes. Saw brown spikes and brambles. His face throbbed. The dripping tap was rain falling off tree branches onto the ground beside him. Cold seeped through him from the earth. He was under a hedge? What?

He flexed his fingers, tried to move his legs, his arms. Instinct told him to keep his movements small and quiet. There had to be a reason he was under a hedge.

Hiding?

That had been such a bad idea. Could have been fatal.

He had no idea how long he’d been under the fucking hedge, but he had to gather himself and move. Even more, he needed to feel his body – at the moment he was numb and that was not a good thing.

Trying not to cry aloud with the pain of it, he rolled out from under the hedge and onto the road.

The full force of the rain hit him hard, opening the cuts on his face, and within moments he was soaked through. At least, he thought grimly, it would wash away some of the blood and the dirt and the grime.

He lay still for a moment, then gritted his teeth and tried to stand.

His blood roared around his body and the mild pounding in his head became ever more fierce. His head swam and he thought he might black out or throw up or both. More deep breathing. Tried to throw his mind elsewhere. Back to sunshine, to laughter, to the hazy feeling of happiness he couldn’t quite grasp.

Then, at least, he was standing straight. Only had one trainer on. Not good.

He shook his head, felt the loose teeth rattle. Spat out blood, but no teeth.

His body was stiff and weak. And it was fucking painful, especially his shoulder. He couldn’t move his arm properly. Had he broken it? Dislocated it? He tried to waggle his fingers and winced. Yep, that worked. Not broken then. Blood was running down his arm onto his fingers. He craned his neck to look. A nasty gash running from shoulder to elbow. Not only dislocated but sliced open. And it didn’t look great. Pieces of grit and mud and grass in the wound. He’d have to find somewhere to wash it.

Christ he felt sick. He started shaking again. Hot. Feverish. The shaking filled his body, stretched from the top of his head to his toes. Falling to his knees, he let the vomit spew out of him, retching until his ribs hurt and there was nothing more to come.

He closed his eyes.

He wanted, no needed – what? He had a memory of being given something, something that made him feel good. It made him feel good but also like a – zombie, that was it. Someone useless, without sense or a mind of their own. He’d been given it quite recently. Who by? Those men? He didn’t want to feel like that again, like his body and mind were jelly and nothing could make an impression on them. No, he wanted to feel like himself again, but somewhere in the deep recesses of his mind he knew he didn’t like that self. That self hurt people.

He stood up again. Slowly. Looked around. It was still dark, though the rain had abated. Right. He needed to get dry, to try and clean his wounds and to get some rest. Then maybe he could think about what he would do.

And at all costs he must avoid those men.

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_89f2b706-1c7a-565d-b10c-4ef80254d97c)

DAY TWO: MORNING (#ulink_28130955-7f30-52a6-9e6f-130f1649068c)

Alex stepped out of the Forum – a modern building constructed of glass that housed the city’s library, a café, a shop and television and radio studios – and into the grey and drizzly daylight. Norwich was getting ready for work, and people splashed to and fro huddled under umbrellas. The market stallholders were busy pulling back the awnings over their stalls and putting goods out on display – all manner of things from spare vacuum cleaner parts to high-end leather goods. The smells of bacon and coffee from the fast-food outlets wafted over to Alex, making her stomach rumble.

The interview down the line to BBC Scotland had gone well, even though she’d been stuck in a small cubbyhole behind the Norfolk radio station’s reception and had to imagine the jolly-voiced person at the other end of the microphone. Still, at least the presenter had read her book and had formed some interesting questions about it. He had even gone on to ask her about her other work, though obviously didn’t want it to get too serious, as he cut her off when she began to go down the mental health route. It seemed she was destined for evermore to be known for her love of coupons.

It made her back itchy. Ever since she had begun her career – one that was blown off course almost straightaway when she became pregnant after an unfortunate one-night stand in Ibiza – she had lurched from one freelance job to another. Heath was right, she had to get off her backside and find herself a project, a decent story. If she wanted to be taken seriously, she had to do something serious. Sure, she had won a lot of professional acclaim for that series on Internet suicide forums, but she knew she was only as good as her last article. Or book. And if she didn’t want to be remembered for all eternity for a book about finding and using money-off vouchers, then she had to get on with it and stop feeling sorry for herself. Give herself a new sense of purpose.

Alex yawned. Sleep had been elusive overnight, images of the crashed car and the broken man flashing through her mind. The blood. The look on his face. Frightened, not relieved when those people turned up to take him to the hospital. She had a nagging feeling that the whole set-up was wrong. Why hadn’t she been more insistent that they told her exactly where they were taking him? Too much drink. Befuddled brain, maybe.

And there had been no call from the police. There had been a crash, a man had been injured, she was a witness. The man in the coat said he would call the police. They would want to talk to her.

Then she remembered she had given one of the men her card. There was no excuse for them not to call. Right. She wasn’t going to wait, she was going to call round the hospitals – there weren’t that many in the area – and find out the state of the injured man. It had been, what? About eleven o’clock when she left Riders’ Farm. Allow about fifteen minutes for the walk down the road and then another three quarters of an hour for them to get to a hospital, so, it would be somewhere around midnight when he arrived, a bit longer if they went to the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital. She turned and went back into the Forum.

Five minutes later and she was in the radio cubbyhole again. The man on reception had assured her that it wasn’t going to be used until lunchtime and said she was welcome to make her calls from there and could he have her autograph. For his mother. Of course.

She took her damp coat off again and settled down and spent fifteen frustrating minutes on the phone. No injured person had been brought in by one or two men at midnight to any of the hospitals she called – Norwich, Ipswich, Great Yarmouth and Bury St Edmunds. She even tried Colchester just in case. The only road traffic accident victims had been taken to hospital by ambulance.

‘Sorry, love,’ said a kind nurse at Colchester. ‘Are you sure you weren’t mistaken? Maybe the man wasn’t that badly hurt after all and they took him home.’

Had she been mistaken? Could the blood and bruising have been superficial? You did hear about people walking away from horrific crashes without a scratch on them – perhaps that was it?

No, he had definitely been in pain, definitely needed hospital treatment.

‘Maybe. Thank you for your help.’

‘I hope you find him, love.’