Читать онлайн книгу «The Wychford Poisoning Case» автора Anthony Berkeley

The Wychford Poisoning Case

Anthony Berkeley

Tony Medawar

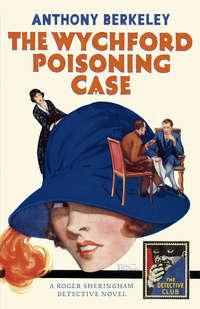

One of the earliest psychological crime novels, back in print after more than 80 years.Mrs Bentley has been arrested for murder. The evidence is overwhelming: arsenic she extracted from fly papers was in her husband’s medicine, his food and his lemonade, and her crimes are being plastered across the newspapers. Even her lawyers believe she is guilty. But Roger Sheringham, the brilliant but outspoken young novelist, is convinced that there is ‘too much evidence’ against Mrs Bentley and sets out to prove her innocence.Credited as the book that first introduced psychology to the detective novel, The Wychford Poisoning Case was based on a notorious real-life murder inquiry. Written by Anthony Berkeley, a founder of the celebrated Detection Club who also found fame under the pen-name ‘Francis Iles’, the story saw the return of Roger Sheringham, the Golden Age’s breeziest – and booziest – detective.

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#ulink_1d28dd18-f151-536c-99a7-56cc5f622bf9)

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by The Crime Club by W. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1926

Copyright © Estate of Anthony Berkeley 1926

Introduction © Tony Medawar 2017

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1926, 2017

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008216429

Ebook Edition © February 2017 ISBN: 9780008216436

Version: 2016-12-15

Dedication (#ulink_33583ec1-9199-504e-972d-27549e37255f)

TO

E. M. DELAFIELD

MOST DELIGHTFUL OF WRITERS

MY DEAR ELIZABETH,

There is only one person to receive the dedication of the book which has grown out of those long criminological discussions of ours. You will recognise in it many of your own ideas, which I have unblushingly annexed; but I hope you will also recognise the attempt I have made to substitute for the materialism of the usual crime-puzzle of fiction those psychological values which are (as we have so often agreed) the basis of the universal interest in the far more absorbing criminological dramas of real life. In other words I have tried to write what might be described as a psychological detective story.

In any case I offer you the result as a small expression of my admiration of your work and of my gratitude for the gift of your friendship.

Contents

Cover (#u28736fb1-474a-5a16-8ae3-a6fcfab558ec)

Title Page (#uaa613589-97dc-5e7b-a768-33e323213fbd)

Copyright (#u667a3193-197d-5af0-b020-0b8c12684678)

Dedication (#u7fc21405-1743-5528-9d8f-d7cea53dd07c)

Introduction (#u0b6c83d5-2d33-5a26-b23e-6c0c66e24ed5)

I. MARMALADE AND MURDER (#u73b4c108-ef65-5ae3-9a31-6459c5899327)

II. STATING THE CASE (#ud9d05a59-7590-5c41-a39a-06580e81c6f9)

III. MR SHERINGHAM ASKS WHY (#u167ff01c-df87-5ac7-986e-5daf818b7bd3)

IV. ARRIVAL AT WYCHFORD (#u868d73c3-7805-5002-9a71-53603a0a58e2)

V. ALL ABOUT ARSENIC (#ubae8aac9-5343-5a61-9bc8-0c6ed862e8ec)

VI. INTRODUCING MISS PUREFOY (#u80e00909-4c33-5c80-bd05-825c6ad08bc1)

VII. MOSTLY IRRELEVANT (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII. TRIPLE ALLIANCE (#litres_trial_promo)

IX. INTERVIEW WITH A HUMAN BURR (#litres_trial_promo)

X. SHOCKING TREATMENT OF A LADY (#litres_trial_promo)

XI. ENTIRELY FEMININE (#litres_trial_promo)

XII. THE HUMAN ELEMENT (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII. WHAT MRS BENTLEY SAID (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV. INTERVIEW WITH A GREAT LADY (#litres_trial_promo)

XV. MISS BLOWER RECEIVES (#litres_trial_promo)

XVI. CONFERENCE AT AN IRONING-BOARD (#litres_trial_promo)

XVII. MR ALLEN TALKS (#litres_trial_promo)

XVIII. MR SHERINGHAM LECTURES ON ADULTERY (#litres_trial_promo)

XIX. INTRODUCING BENTLEY BROTHERS (#litres_trial_promo)

XX. MR SHERINGHAM SUMS UP (#litres_trial_promo)

XXI. DOUBLE SCOTCH (#litres_trial_promo)

XXII. ENTER ROMANCE (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIII. FINAL DISCOVERIES (#litres_trial_promo)

XXIV. VILLAINY UNMASKED (#litres_trial_promo)

XXV. ULTIMA THULE (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_ded61d05-4085-5120-8f9c-1ba20cb51186)

ANTHONY BERKELEY COX—or Anthony Berkeley as he is best known—was born on 5 July, 1893 in Watford, a town near London. His father was a doctor and his mother was descended from the Earl of Monmouth, a courtier to Queen Elizabeth I. At school, Berkeley was what we would now call a high achiever—Head of House, prefect, Colour Sergeant in the Officer Training Corps and an expert marksman. In 1911, he left school to read Classics at University College, Oxford, but his university career was cut short by the First World War and, between 1914 and 1918, Berkeley served in France in the 7th Northamptonshire Regiment, reaching the rank of Lieutenant, and also in the Royal Air Force.

After the war, Berkeley spent a couple of years ‘trying to find out what nature had intended him to do in life’ before he discovered that he had the most extraordinary knack for writing comic stories for the many weekly magazines and newspapers that carried such fiction in the 1920s. Thankfully, Berkeley also decided to try his hand at something more serious, a detective mystery.

His first attempt, The Layton Court Mystery, was published anonymously in 1925 by Herbert Jenkins. The book marked the debut of Roger Sheringham, a man with more than a hint of his creator about him—in particular, like Berkeley, he was an Oxford man and his health had been compromised during the war. The Layton Court Mystery features a closed circle of suspects and a suitably unpleasant victim who is found dead in a locked room; the murderer’s identity comes as a devastating surprise. In dedicating the novel to his father, Berkeley explained that he had ‘tried to make the gentleman who eventually solves the mystery behave as nearly as possible as he might be expected to do in real life. That is to say, he is very far removed from a sphinx and he does make a mistake or two occasionally.’

Sheringham’s tendency to make ‘a mistake or two occasionally’ may very well have been inspired by E.C. Bentley’s famous novel Trent’s Last Case, published a dozen years earlier. Certainly, fallibility was to become something of a trademark for Roger Sheringham.

The Layton Court Mystery sold well and, enthused by the sales figures, Anthony Berkeley decided to focus on writing novels and to make Roger Sheringham the central figure of a series of mysteries. Sheringham’s second case, also published anonymously (the byline of the jacket was simply ‘By the author of The Layton Court Mystery’), was The Wychford Poisoning Case.

The Wychford Poisoning Case (1926) is the rarest of Berkeley’s detective fiction. It was the first of his novels to be published by Collins but, unlike other Sheringham mysteries, has not until now been reissued, even in a paperback edition. It is unclear why this was but it has been suggested that it may have been because Berkeley felt acute embarrassment at a brief, irrelevant but bizarre scene in which an annoying young woman is subjected to corporal punishment. Whether or not the scene was meant ironically or simply as comic relief, it reads oddly today and, as with the casual anti-semitism that pollutes some Golden Age mysteries, leaves modern readers uncomfortable. Sexist aberrations aside, the novel is strong and the explanation of the poisoning is characteristically unexpected and outrageous. It is also noteworthy for being dedicated to Berkeley’s long-standing friend, the aristocratic Edmée Elizabeth Monica de la Pasture under her rather more prosaic pseudonym, E.M. Delafield.

Unlike The Layton Court Mystery, The Wychford Poisoning Case is based on a real-life murder—that of James Maybrick, a Liverpool businessman, in 1889. Like many other writers of the era, Berkeley had a deep interest in what has come to be called ‘true crime’, writing essays on various different cases over the years—indeed, The Wychford Poisoning Case would not be the only occasion on which Berkeley would draw on what he called ‘the far more absorbing criminological dramas of real life’. The Wychford Poisoning Case is also notable for the innovative consideration of psychology as a method of crime detection, pioneered some fifteen years earlier by Edwin Balmer and William MacHarg with their stories of Luther Trant. This was an approach that Anthony Berkeley would eventually perfect with Malice Aforethought (1931), in which he gave an ingenious study of a murderer, and in two other novels, all of which were published under a different pen name, Francis Iles.

The first two Sheringham mysteries sold well and the detective’s popularity was such that his name would be included in the title of the third, Roger Sheringham and the Vane Mystery (1927), which for the first time in the series was published as by Anthony Berkeley.

In all, Sheringham appears in ten novel-length detective stories, one of which, The Silk Stocking Murders (also reissued in this Detective Club series), is dedicated by Berkeley to none other than A.B. Cox! Sheringham is also mentioned in passing in two of Berkeley’s non-series novels, The Piccadilly Murder (1929) and Trial and Error (1937), and appears in a novella and a number of short stories, including two recently discovered ‘cautionary’ detective problems published during the Second World War.

Though undoubtedly one of the ‘great detectives’ of the Golden Age, Roger Sheringham is not a particularly original creation. As already noted, there is much of E.C. Bentley’s Philip Trent about Sheringham, as there is about many other Golden Age detectives, including Margery Allingham’s Albert Campion and Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey. And, emulating Bentley’s iconoclastic approach to the genre, Berkeley delighted in turning its unwritten rules upside down. Thus, while Sheringham’s cases conform, broadly, to the principal conventions of the detective story—there is always a crime and there is always at least one detective—the mysteries are distinctive and memorable for the way in which they drove the evolution of crime and detective stories. Each of the novels brings something new and fresh to what Berkeley had previously dismissed as the ‘crime-puzzle’. Several do have what can be described as twist endings but that is to diminish Berkeley’s ingenuity and undervalue his importance in the history of crime and detective fiction.

While other luminaries wrought their magic consistently—Agatha Christie in making the most likely suspect the least likely suspect, and John Dickson Carr in making the impossible possible—Anthony Berkeley delighted in finding different ways to structure the crime story. ‘Anthony Berkeley is the supreme master not of “the twist” but of the “double twist”,’ wrote Milward Kennedy in the Sunday Times, but his focus was not so much on adding a twist at the end but on twisting the genre itself.

Astonishingly, it is more than 75 years since the publication of Berkeley’s final novel, As for the Woman (1939), which appeared under the pen name of Francis Iles. And yet his influence lives on. Berkeley did much to shape the evolution of crime fiction in the 20th century and to transform the ‘crime puzzle’ into the novel of psychological suspense. In the words of one of his peers, Anthony Berkeley Cox—more than most—‘deserves to become immortal’.

TONY MEDAWAR

September 2016

CHAPTER I (#ulink_e0afdc58-a413-554c-9390-6329ae031c2d)

MARMALADE AND MURDER (#ulink_e0afdc58-a413-554c-9390-6329ae031c2d)

‘KEDGEREE,’ said Roger Sheringham oracularly, pausing beside the silver dish on the sideboard and addressing his host and hostess with enthusiasm, ‘kedgeree has often seemed to me in a way to symbolise life. It can be so delightful or it can be so unutterably mournful. The crisp, dry grains of fish and rice in your successful kedgeree are days and weeks so easily surmountable, so exquisite in their passing; whereas the gloomy, sodden mass of an inferior cook—’

‘I warned you, darling,’ observed Alec Grierson to his young wife. ‘You can’t say I didn’t warn you.’

‘But I like it, dear,’ protested Barbara Grierson (née Shannon). ‘I like hearing him talk about fat, drunken cooks; it may be most useful to me. Go on, Roger!’

‘I don’t think you can have been attending properly, Barbara,’ said Roger in a pained voice. ‘I was discoursing at the moment upon kedgeree, not cooks.’

‘Oh! I thought you said something about the gloomy mass of a sodden cook. Never mind. Go on, whatever it was. I ought to warn you that your coffee’s getting cold, though.’

‘And you might warn him at the same time that it’s past ten o’clock already,’ added her husband, applying a fresh match to his after-breakfast pipe. ‘Hadn’t you better start eating that kedgeree instead of lecturing on it, Roger? I was hoping to be at the stream before this, you know. I’ve been ready for the last half-hour.’

‘Vain are the hopes of men,’ observed Roger sadly, carrying a generously loaded plate to the table. ‘In the night they spring up and in the morning, lo! cometh the sun and they are withered and die.’

‘In the morning cometh Roger not, who continueth frowsting in bed,’ grumbled Alec. ‘That’d be more to the point.’

‘Cease, Alexander,’ Roger retorted gently. ‘The efforts of your admirable cook engage me.’

Alec picked up his newspaper and began to study its contents with indifferently concealed impatience.

‘Did you sleep well, Roger?’ Barbara wanted to know.

‘Did he sleep well?’ growled her husband, with heavy sarcasm. ‘Oh, no!’

‘Thank you, Barbara; very well indeed,’ Roger replied serenely. ‘Really, you know, that cook of yours is a culinary phenomenon. This kedgeree’s a dream. I’m going to have some more.’

‘Finish the dish. Now then, aren’t you sorry you wouldn’t come and stay with us before?’

‘Not in the least. In fact, I’m still congratulating myself that I resisted the awful temptation. One of the wisest things I ever did in all my life, compact with wisdom though it has been.’

‘Oh? Why?’

‘For any number of reasons. How long have you been married now? Just over a year? Exactly. It takes precisely twelve months for a married couple to get sufficiently used to each other without having to be maudlin in public, to the extreme embarrassment of middle-aged bachelors and unsympathetic onlookers such as myself.’

‘Roger!’ exclaimed his indignant hostess. ‘I’m sure Alec and I have never said a single—’

‘Oh, I’m not talking about words. I’m talking about expressive glances. My dear Barbara, the expressive glances I’ve had to sit and writhe between in my time! You wouldn’t believe it.’

‘Well, I should have thought you’d have enjoyed that sort of thing,’ Barbara laughed. ‘All’s copy that comes into your mill, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t write penny novelettes, Mrs Grierson,’ returned Roger with dignity.

‘Don’t you?’ Barbara replied innocently.

An explosive sound burst from Alec. ‘Good for you, darling. Had him there.’

‘You are pleased to insult me, the two of you,’ said Roger pathetically. ‘Helpless and in your power, speechless with kedgeree—’

‘No, not speechless!’ came from the depths of Alec’s paper. ‘Never that.’

‘Speechless with kedgeree, squirming with embarrassment in the presence of your new relationship to each other—’

‘Roger, how can you! When you yourself were Alec’s best man, too!’

‘You put me between you and insult me. The very first morning of my visit, too. What are the trains back to London?’

‘There’s a very good one in about half an hour. And now tell me all the other reasons why you wouldn’t come down here before.’

‘Well, for one thing I set a certain value on my comfort, Barbara, and other regrettable experiences, over which we will pass with silent shudders, have shown me very clearly that it takes a wife a full twelve months to learn to run her house with sufficient dexterity and knowledge to warrant her asking guests down to it.’

‘Roger! This place has always gone like clockwork ever since I took it over. Hasn’t it, Alec?’

‘Clockwork, darling,’ mumbled her husband absently.

‘But then, you’re a very exceptional woman, Barbara,’ said Roger mildly. ‘In the presence of your husband I can’t say less than that. He’s bigger than me.’

‘Roger, I don’t think I’m liking you very much this morning. Have you finished the kedgeree? Well, you’ll find some grilled kidneys in that other dish. More coffee?’

‘Grilled kidneys?’ said Roger, rising with alacrity. ‘Oh, I am going to enjoy my stay here, Barbara. I suspected it at dinner last night. Now I know.’

‘Are you going to be all the morning over brekker, Roger?’ demanded Alec in desperation.

‘Most of it, Alexander, I hope,’ Roger replied happily.

For nearly two minutes the silence was unbroken.

‘Anything in the paper this morning, dear?’ Barbara asked casually.

‘Only this Bentley case,’ replied her husband without looking up.

‘The woman who poisoned her husband with arsenic? Anything fresh?’

‘Yes, the magistrates have committed her for trial.’

‘Anything said about her defence, Alec?’ asked Roger.

Alex consulted the paper. ‘No; defence reserved.’

‘Defence!’ said Barbara with a slight sniff. ‘What a hope! If ever a person was obviously guilty—!’

‘There,’ said Roger, ‘speaks the voice of all England—with two exceptions.’

‘Exceptions? I shouldn’t have thought there was a single exception. Who?’

‘Well, Mrs Bentley, for one.’

‘Oh—Mrs Bentley. She knows what she did all right.’

‘Oh, no doubt. But she couldn’t have thought she was being obviously guilty, could she? I mean, she’s a curious sort of person if she did.’

‘But she is rather a curious sort of person in any case, isn’t she? Ordinary people don’t feed their husbands on arsenic. And who’s the other exception?’

‘Me,’ said Roger modestly.

‘You? Roger! Do you mean to say you think she’s not guilty?’

‘Not exactly. It was just the word “obviously” that I was taking exception to. After all, she hasn’t been tried yet, you know. We haven’t heard yet what she’s got to say about it all.’

‘What can she say? I suppose she’ll fake up some sort of story, but really, Roger! All I can say is that if they don’t hang her, no husband’s life will ever be safe again.’

‘Then let’s hope they do,’ remarked Alec humorously. ‘Speaking entirely from the personal point of view, of course.’

‘Prejudice, thy name is woman,’ Roger murmured. ‘Second name, apparently, bloodthirstiness. It’s wonderful. We’re all being women over this affair. Marmalade, please, Alexander.’

‘I know you’re a perverse old devil, Roger,’ Alec was constrained to protest as he passed the dish across, ‘but you can’t mean to say that you really think she’s innocent?’

‘I don’t think anything of the sort, Alexander. What I am trying to do (which apparently no one else is) is to preserve an open mind. I repeat—she hasn’t been tried yet!’

‘But the coroner’s jury brought it in murder against her.’

‘Even coroner’s juries have been known to be fallible,’ Roger pointed out mildly. ‘And they didn’t bring it in quite as bluntly as that. Their exact words, as far as I remember, were that Bentley died from the administration of arsenic, and the majority were of the opinion that the arsenic had been administered with the intention of taking away life.’

‘That comes to the same thing.’

‘Possibly. But it isn’t conclusive.’

‘You seem to know a lot about this case, Roger,’ Barbara remarked.

‘I do,’ Roger agreed. ‘I’ve tried to read every word that’s been written about it. I find it an uncommonly interesting one. After you with that paper, Alec.’

Alec threw the paper across. ‘Well, there was a lot of new evidence brought before the magistrates yesterday. You’d better read it. If you can keep an open mind after that, call the rest of us oysters.’

‘I do that already,’ Roger replied, propping the paper up in front of him. ‘Thank you, Oyster Alexander.’

CHAPTER II (#ulink_edcc4bd0-a5ed-505a-ac9e-37f8178c91c8)

STATING THE CASE (#ulink_edcc4bd0-a5ed-505a-ac9e-37f8178c91c8)

‘ALEC,’ said Roger, as he settled his back comfortably against a shady willow and pulled his pipe out of his pocket. ‘Alec, I would reason with you.’

It was a glorious morning at the beginning of September. The two men had managed after all to put in a couple of hours’ fishing in the little trout-stream which ran through the bottom of the Grierson’s estate, in spite of Roger’s lingering over his kedgeree and kidneys. Twenty minutes ago they had broken off for the lunch of sandwiches and weak whisky-and-water which they had brought with them, and these having now been despatched Roger was feeling disposed to talk.

For once in a while Alec was not unwilling to encourage him. ‘About the Bentley case?’ he said. ‘Yes, I’ve been meaning to ask you about that. What’ve you got up your sleeve?’

‘Oh, nothing up my sleeve,’ Roger said, cramming tobacco into the enormous bowl of his short-stemmed pipe. ‘Nothing as definite as that. But I must say I am most infernally interested in the case, and there’s one thing about it that strikes me very forcibly. Look here, would it bore you if I ran through the whole thing and reviewed all the evidence? I’ve got it all at my fingers’ tips, and it would help to clarify it in our minds, I think. Just facts. I mean, without all the prejudice.’

‘Not a bit,’ Alec agreed readily. ‘We’ve got half an hour to smoke our pipes in anyhow, before we want to get going again.’

‘I think you might have put it a little better than that,’ Roger said with reproach. ‘However! Now let me see, what’s the beginning of the story? The Bentley ménage, I suppose. No, further back than that. Wait a minute, I’ve got some notes here.’

He plunged his hand into the breast-pocket of the very disreputable, very comfortable sports’ coat he was wearing and drew out a small note-book, which he proceeded to study for a minute or two.

‘Yes. We’d better go over the man’s whole life, I think. Well, John Bentley was the eldest of three brothers, and at the time of his death he was forty-one years old. At the age of eighteen he entered his father’s business of general import and export merchants, specialising in machine-tools, and spent six years in the London office. When he was twenty-four his father sent him over to France to take charge of a small branch which was being opened in Paris, and he remained there for twelve years, including the period of the war, in which he was not called upon to serve. During that time he had married, at the age of thirty-four, a Mademoiselle Jacqueline Monjalon, the daughter of a Parisian business acquaintance, since dead; his bride was only eighteen years old. Is that all clear?’

‘Most lucid,’ said Alec, puffing at his pipe.

‘Two years after his marriage, Bentley was recalled to London by his father to assume gradual control of the whole business, which was then in a very flourishing condition, and this he proceeded to do. There was another brother in the business, the second one; but this gentleman had not been able to elude his duties to his country and had been conscripted in 1916, subsequently serving for eighteen months in France till badly wounded in the final push. From a certain wildness which I seem to trace in some of his statements to the press and elsewhere, I should diagnose a dose of shell-shock as well.’

‘Diagnosis granted,’ Alex agreed: ‘I noticed that. Hysterical kind of ass, I thought. Go on.’

‘Well, when our couple returned from France, they bought a large and comfortable house in the town of Wychford, which lies about fifteen miles south-east of London and possesses an excellent train-service for the tired businessman. Thence, of course, friend John would travel up to town every day except Saturdays, a day on which nobody above the rank of assistant-manager dare show his face in the streets of London or everybody would think his firm is going bankrupt: remember that if you ever go into business, Alec.’

‘Thanks, I will.’

‘Well, eighteen months after the Bentley’s arrival in England, the father, instead of retiring from work in the ordinary way, makes a better job of it and dies, leaving the business to the two sons who are in it, in the proportion of two-thirds to John and one-third to William, the second son. To the third son, Alfred, he left most of the residue of his estate, which amounted in value to much the same as William’s share of the business. John, then, who seems to have been the old man’s favourite, came off very decidedly the best of the three. John therefore picked up the reins of the business and for the next three years all went well. Not quite so well as it had done, because John wasn’t the man his father had been; still, well enough. So much, I think, for the family history. Got all that?’

Alec nodded. ‘Yes, I knew most of that before, I think.’

‘So now we come from the general to the particular. In other words, to the Bentley ménage. Now, have you formed any estimate of the characters of these two, Monsieur and Madame? Could you give me a short character-sketch of Bentley himself, for instance?’

‘No, I’m blessed if I could. I was concentrating on the facts, not the characters.’

Roger shook his head reprovingly. ‘A great mistake, Alexander; a great mistake. What do you think it is that makes any great murder case so absorbingly interesting? Not the sordid facts in themselves. No, it’s the psychology of the people concerned; the character of the criminal, the character of the victim, their reactions to violence, what they felt and thought and suffered over it all. The circumstances of the case, the methods of the murderer, the reasons for the murder, the steps he takes to elude detection—all these arise directly out of character; in themselves they’re only secondary. Facts, you might say, depend on psychology. What was it that made the Thompson-Bywaters case so extraordinarily interesting? Not the mere facts. It was the characters of the three protagonists. Take away the psychology of that case and you get just a sordid triangle of the most trite and uninteresting description. Add it, and you get what the film-producers call a drama packed with human interest. Just the same with the Seddon case, Crippen, or, to become criminologically classical, William Palmer. A grave error, my Alexander; a very grave error indeed.’

‘Sorry; I seem to have said the wrong thing. All right. What about the psychology of the Bentleys, then?’

‘Well, John Bentley seems to emerge to me as a fussy, rather irritating little man, very pleased with himself and continually worrying about his health; probably a bit of a hypochondriac. Reading between the lines, I don’t think brother William got on at all well with him—no doubt because he was much the same sort of fellow himself. It doesn’t need any reading between the lines to see that his wife didn’t. She appears as a happy, gay little creature, not overburdened with brains but certainly not deficient in them, always wanting to go out somewhere and enjoy herself, theatres, dance-clubs, car-rides, parties, any old thing. Well, just imagine the two of them together—and remember that she’s sixteen years younger than her husband. She wants to go to a dance, he won’t take her because it would interfere with his regular eight-hours’ sleep; she wants to go to a race-meeting, he thinks standing about in the open air would give him a cold; she wants to go to the theatre, he thinks the man in the next seat might be carrying influenza germs. Of course the inevitable happens. She gets somebody else to take her.’

‘Ah!’ observed Alec wisely. ‘Allen!’

‘Exactly! Allen. Well, that’s where the facts of the case proper seem to begin; with that weekend Mrs Bentley spent with Allen at the Bischroma Hotel.’

‘Now we’re getting to it.’

Roger paused to re-light his pipe, which had gone out under the flood of this eloquence.

‘Now,’ he agreed, ‘we’re getting to it. That was on the 27th of June; Mrs Bentley going home to Wychford again on the 29th and telling her husband that she’d been staying with a girl friend of hers from Paris. Bentley doesn’t seem to have suspected anything: which is what one might expect with that complacent, self-centred little type. But he has got his doubts about Allen. Allen’s name crops up in the conversation that same night, we learn from brother William, who was staying in the house for the whole summer, and Bentley forbids his wife to have anything more to do with the chap. Madame laughs at him and asks if he’s jealous.’

‘The nerve of her!’

‘Oh, quite natural, in the circumstances. He says he’s not jealous in the least, thank you, but he’s just given her his instructions and will she be kind enough to see that they are carried out (can’t you just see him at it!) Madame, ceasing to laugh, tells him not to be an ass. Bentley retorts suitably. Anyhow, the upshot is that they have a blazing row, all in front of brother William, and Madame flies upstairs, chattering with fury, to pack her bag for France that very minute.’

‘Pity she didn’t!’

‘I agree. Brother William steps in, however, and persuades her to stay that night at any rate, and in the morning he gets in a Mrs Saunderson from down the same road, with whom Mrs Bentley has been getting very pally during the last couple of years, and she manages to pacify the lady to such an extent that there is a grand reconciliation scene that same evening, with John and Jacqueline in the centre surrounded by the triumphant beams of Brother William and Mrs Saunderson. That was on June the 29th. On July the 1st Mrs Bentley buys two dozen arsenical fly-papers from a chemist in Wychford.’

‘Well, you must admit that’s suspicious, at any rate.’

‘Oh, I do. Suspicious isn’t the word. The parlourmaid, Mary Blower, and the housemaid, Nellie Green, both see these fly-papers soaking in three saucers during the next two days in Mrs Bentley’s bedroom. There had never been fly-papers of that kind in the house before, and they were not a little intrigued about them; Mary Blower especially, as we shall see later. That same day Bentley, fussing as usual over his health, goes to see his doctor in Wychford, Dr James, and gets himself thoroughly over-hauled. Dr James tells him that he’s a little run down (the stock comment for people of that kind), but that there’s nothing constitutionally wrong with him; he gives the man a bottle of medicine to keep him quiet, a mild tonic, mostly iron. Four days later, on a Sunday, Bentley complains at breakfast that he’s not feeling up to the mark. William tells us with a properly shocked air that Mrs Bentley received this information callously and told him straight out that there was nothing the matter with him; but really, the poor lady must have heard the same thing at so many breakfasts before that one can understand her not being exactly prostrated by it. In any case, he’s not feeling so bad that he can’t go out for a picnic that same afternoon with her and William, and Mr and Mrs Allen.’

‘Having climbed down over the Allen business, apparently,’ Alec commented.

‘Yes. But of course he had to. With the possible exception of Mrs Saunderson, the Allens were their closest friends in Wychford. Unless he wanted to precipitate an open scandal, he couldn’t maintain his stand about Allen. To do so would be tantamount to informing Mrs Allen that, in Bentley’s opinion, her husband was in danger of becoming unfaithful to her. One’s sympathies are certainly with Bentley there; the position was a very nasty one for him. And I can’t imagine him liking the man much. They must have been complete opposites, mustn’t they? Bentley, fussy, peevish, and on the small side; Allen, big, breezy, hearty, strong, and packed with self-confidence—or so I read him. Yes, I can quite understand Bentley’s uneasiness about friend Allen just about that time.’

‘And Mrs Allen didn’t know her husband was taking Mrs Bentley out all this time?’

‘So I should imagine. She probably guessed he was taking somebody out, but not that it was Mrs Bentley. I can’t quite get Mrs Allen. She seemed perfectly calm, even icy, in the police-court; and probably her deliberate manner did Mrs Bentley actually more harm than Mrs Saunderson’s hysteria. She is the wronged wife, you see, and she’s certainly investing an ignominious rôle with a good deal of quiet dignity. Mrs Saunderson’s the person who appears to me to emerge worse than anybody else in the whole case; she seems really rancorous against her late best friend. What inhuman brutes some of these women can be to each other, when one of them’s properly up against it! However. Well, Bentley comes back from the picnic complaining that he feels a good deal worse and goes straight to bed, where shortly afterwards he is very sick. He attributes his trouble to sitting about on damp grass at the picnic; the police say that it followed the first administration to him by his wife of the solution of arsenic obtained from the fly-papers.’

‘Um!’ said Alec thoughtfully.

‘He passed a fairly good night, but stayed in bed during the next day though feeling decidedly better. Dr James called in during the morning and, after a thorough examination, came to the conclusion that the man was a chronic dyspeptic. He changed his medicine and gave instructions about his diet, and the next day, Tuesday, Bentley was well enough to go back to business. That same night Mrs Bentley went with Allen to the Four Arts Ball at Covent Garden, the last big public event of the season, going back with him afterwards to the Bischroma again. The evidence of the proprietor, Mr Nume, is quite conclusive on that point.’

‘Bit risky, after the last row.’

‘Oh, yes, risky enough. But as I see Madame Bentley at that time (leaving the question of her subsequent guilt or innocence out of it for the moment), she just didn’t care a rap what happened. We don’t know whether she was really in love with Allen or not, but we do know that her middle-aged husband not only bored her, but irritated her as well; and in these circumstances a woman is simply ripe for madness. The effects of the late reconciliation had probably quite worn off, and she simply didn’t mind whether she were found out or not. Quite possibly she hoped she would be, so that Bentley would divorce her and give her her freedom. There were no children to complicate things, you see.’

‘Might be something in that,’ Alec admitted.

‘Well, after that matters begin to move swiftly. There’s a blazing row when she gets back the next day, and this time Bentley loses his head altogether, knocks her down and gives her a black eye. Again Madame flies upstairs to pack for France, again brother William and Mrs Saunderson intervene in the rôle of good angels, and again the quarrel is patched up somehow or other. Madame Bentley stays at home. That is Wednesday. Bentley has been to his office that day, and he goes on Thursday too, this time taking in a thermos flask some food specially prepared for him by Mrs Bentley herself. He left the flask there, as you know; the residue inside was subsequently analysed and it was found to contain arsenic.’

‘How is she going to get over that?’

‘How, indeed? That’s just what I’m wondering. On this day, Thursday, Bentley’s younger brother, Alfred, calls in during the morning and Bentley tells him that, in consequence of his wife’s behaviour, he is altering his will, leaving her only a bare pittance; nearly the whole of his estate, which consisted chiefly of his holding in the business, he is dividing between his two brothers—not much to William, because he and William don’t get on very well, by far the greater share to Alfred himself. On his death, therefore, Alfred will own the larger holding in the business, although he has never been in it and William has been there all his life.’

‘Yes, I saw that. Why on earth did he do that?’

‘Well, it’s obvious enough. Bentley, though a big enough fool in private life, wasn’t so in business at all. William, on the other hand, was, and Bentley knew it. Once let the business get into William’s full control, and in no time it would go pop. Alfred, on the contrary, is a very different sort of fellow—very different from both his brothers. His character strikes me as more like that of a Scotch elder than a member of the Bentley family—dour, stern, uncompromising, hard and not far removed from cruel; also a bit, if I’m not wrong, on the avaricious side. An amazing contrast. Anyhow, there can’t be a better way of throwing light on his character than by reminding you that as soon as he heard this news, prudent brother Alfred took his brother off to a solicitor there and then that very morning and stood over him while the new will was drawn up! Oh, a very canny man, brother Alfred.’

‘I think I prefer him to Bentley himself though, for all that.’

‘That’s the Scotch strain in you coming out, Alec; you recognise a fellow-feeling for brother Alfred, no doubt. Well, and so we come to Bentley’s last illness and death. Do you want to break off here and go on tickling the trout?’

‘No!’ said Alec surprisingly. ‘It’s rather interesting to hear the whole thing like this in one connected whole instead of in snippets; though what you’re getting at I’m hanged if I can see. Carry on!’

‘Alec,’ said Roger with emotion, ‘this is the most remarkable tribute I have ever had in the course of a long and successful career.’

CHAPTER III (#ulink_262aa54a-7659-5d8c-a89a-266f64eb0291)

MR SHERINGHAM ASKS WHY (#ulink_262aa54a-7659-5d8c-a89a-266f64eb0291)

‘THE next day,’ Roger continued after a short pause, ‘Friday, the 10th of July, Bentley felt too ill in the morning to go to work. He complained of pains in the leg, and was vomiting. Dr James was called in and prescribed for him. The next day the pains had disappeared, but the vomiting continued, which Dr James attributed to the morphia he had given him on the previous day. On the Sunday he was a little better; on the Monday a little better still. On the next day Dr James expected him to be almost recovered, but instead of this a slight relapse set in and, on Mrs Bentley’s suggestion, another doctor was called in, Dr Peters. Dr Peters also diagnosed acute dyspepsia, and gave the patient a sedative. On the Wednesday he was no better.

‘Now this day, the 15th of July, is a very important one indeed, and we must examine it in some detail. It was in the course of this day that the idea was first mooted that all was not as it should be.

‘All this time Mrs Allen and Mrs Saunderson had been continually in and out of the house, while Mrs Bentley was nursing her husband—doing the household shopping for her, running errands, giving advice and generally fussing round. On this evening Mary Blower (who seems to have a grudge of some sort against her mistress) told Mrs Saunderson of the fly-papers she had seen soaking a fortnight before. Mrs Saunderson, twittering with excitement, tells Mrs Allen, and in three minutes these two excellent ladies have decided that Mrs Bentley is poisoning her husband. And since that time not a single person seems to have had the least doubt of it. Off goes Mrs Saunderson to telephone brother William at the office and tell him to come back to Wychford at once, while Mrs Allen runs round to the post-office to send a mysterious telegram to brother Alfred. Of all this Mrs Bentley, of course, remains in complete ignorance. Late in the morning the brothers arrive, and you can imagine the seething excitement.

‘In the meantime, Mrs Bentley has decided that she can’t go on nursing her husband alone and has telegraphed for a nurse, who arrived just after lunch. Brother Alfred, who already seems to have assumed entire control of the household, takes the nurse aside at once and tells her that nobody but herself is to administer anything to the patient, as they have reason to believe that something mysterious is going on. With the consequence that we now have a twittering nurse as well as twittering friends and twittering brothers. In fact, the only person in the house just at that time who does not seem to have been twittering is Mrs Bentley herself.

‘But there’s more excitement to come. During the afternoon Mrs Bentley handed a letter to Mary Blower and asked her to run out to the post with it. Mary Blower looks at the address and sees that it is to Mr Allen, who was at this time away from Wychford on business in Bristol. Instead of posting it, she hands it over to Mrs Allen, who promptly opens it. And then the fat was in the fire with a vengeance, for Mrs Bentley had not only been idiot enough to make reference to their weekend at the Bischroma, but she had mentioned her husband’s illness in terms that certainly weren’t very sympathetic—though it’s more than possible that she didn’t then realise the serious state he was in.

‘Anyhow, coming after the fly-papers revelation, that was enough for the four. Where there had been any possibility of doubt before, there was none now. Brother Alfred put on his hat at once, went round to the two doctors and told them both the whole story. The three of them held a council of war, and decided that Mrs Bentley must be watched continuously.

‘Well, that was bad enough, but there was still another piece of news waiting for brother Alfred when he got back, and that certainly is the most damning thing of all. The nurse had come down a short time ago with a bottle of Bovril in her hand and explained that she had seen Mrs Bentley pick it up in a surreptitious way and convey it out of the bedroom, hiding it in the folds of her frock; a few minutes later she brought it back and replaced it, when she thought the nurse’s back was turned, in the exact spot from which she had taken it. That bottle was handed over to the doctors next day and was subsequently found to contain arsenic.’

‘Well, that I am dashed if you can get over!’ Alec observed.

‘It isn’t for me to get over it,’ pointed out Roger mildly. ‘I’m not saying the woman is innocent. All I say is that we ought to bear the possibility of her innocence in mind, and not assume her guilt as a matter of course. In any case I am most uncommonly interested to hear what she’s got to say about that particular incident. Well, up to this time, you’ve got to remember, Bentley’s condition, though serious, wasn’t considered to be in any way dangerous (which does go a long way to explain the somewhat flippant tone of Mrs Bentley’s letter to Allen that has helped to create so much prejudice against her); but that same night things took a very rapid turn for the worse. Both doctors were hurriedly summoned, and they were with him all night. By the next morning Mrs Bentley and the others were warned that there could be very little hope for him, at midday he became unconscious and at seven o’clock in the evening he died.

‘But that wasn’t all. Mrs Bentley had been removed at once, by brother Alfred’s orders, to her own bedroom, where she was kept practically a prisoner, and the other four immediately began a systematic search of the whole place. Their efforts were not unrewarded. In Bentley’s dressing-room there stood a trunk belonging to his wife. In the tray of this was a medicine bottle containing, as shown later, a very strong solution of arsenic in lemonade, together with a handkerchief belonging to Mrs Bentley which was also impregnated with arsenic. In a medicine-chest were the remains of the bottles of medicine prescribed by Dr James (two) and Dr Peters (one). None of these prescriptions contained arsenic, but arsenic was subsequently discovered in each bottle in appreciable quantities. And lastly, in a locked drawer in Mrs Bentley’s own bedroom there was found a small packet containing no less than two whole ounces of pure arsenic—actually enough to kill more than a couple of hundred people! And that was that.’

‘I should say it was!’ Alec agreed.

‘Of course the doctors refused a death-certificate. The police were called in, and Mrs Bentley was promptly arrested. Two days later a post-mortem was held. There was no doubt about the cause of death. The stomach and the rest of it were badly inflamed. Death due to inflammation of the stomach and intestines set up by an irritant poison—which in this case was the medical way of saying death from arsenical poisoning. The usual parts of the body were removed and placed in sealed jars for examination by the Government analyst. You read the result this morning in his evidence before the magistrates—at least three grains of arsenic in the body at the time of death, or half a grain more than the ordinary fatal dose, meaning that shortly before death there must have been a good deal more still; arsenic in the stomach, intestines, liver, kidneys, everywhere! And also, significant in another way, arsenic in the skin, nails and hair; and that means that arsenic must have been administered some considerable time ago—a fortnight, for instance, or about the time of that picnic. Is it any wonder that the coroner’s jury brought in a verdict tantamount to wilful murder against Mrs Bentley, or that the magistrates have committed her for trial?’

‘It is not!’ said Alec with decision. ‘They’d have been imbeciles if they hadn’t.’

‘Quite so,’ said Roger. ‘Exactly.’ And he began to smoke very thoughtfully indeed.

There was a little pause.

‘Come on,’ said Alec. ‘You know you’ve got something up your sleeve.’

‘Oh, no. I’ve got nothing up my sleeve.’

‘Well, there’s something in your mind, then. Let’s have it!’

Roger took his pipe out of his mouth and pointed the short stem at his companion as if to drive his next remark home with it. ‘There is a question that I can’t find an answer to,’ he said slowly, ‘and it’s this—why the devil so much arsenic?’

‘So much?’

‘Yes. Why enough to kill a couple of hundred people when there’s only one to be killed? Why? It isn’t natural.’

Alec pondered. ‘Well, surely there might be two or three explanations of that. She wanted to make sure of the job. She didn’t know what the fatal dose was. She—’

‘Oh, yes; there are two or three explanations. But not one of them is the least bit convincing. You don’t think people go in for poisoning without finding out what the fatal dose is, do you? Poisoning is a deliberate, cold-blooded job. Such a simple measure as looking up the fatal dose in any encyclopædia or medical reference book would be the very first step.’

‘Um?’ said Alec, not particularly impressed.

‘And then there’s another thing. Why in the name of all that’s holy buy fly-papers when there’s all that amount of arsenic in the house already?’

‘But perhaps there wasn’t,’ Alec retorted quickly. ‘Perhaps she got the other arsenic after the fly-papers.’

‘Well, suppose she did. The same objection applies just as well. Why buy all that amount of arsenic when she’d already got half a dozen fatal doses out of the fly-papers? And once more, I haven’t seen any police evidence offered to prove that Mrs Bentley did buy that arsenic. It’s proved to have been in her possession, but it hasn’t been shown how it came there. The police seem to be taking it completely for granted that as she had it, it must have been she who bought it.’

‘Is that very important?’

‘I should have said, vitally! No, look at it how you like, the question of this superabundance of arsenic does not simplify the case, as everybody seems to have assumed; in my opinion it infernally complicates it.’

‘It is interesting,’ Alec admitted. ‘I’d never looked on it like that before. What do you make of it, then?’

‘Well, there seem to me only two possible deductions. Either Mrs Bentley is the most imbecile criminal who ever existed and simply went out of her way to manufacture the most damning evidence against herself—which, having formed my own opinion of her character, I am most unwilling to believe. Or else—!’ He paused and rammed down a few straggling ends of tobacco into the bowl of his pipe.

‘Yes?’ Alec asked with interest. ‘Or else what?’

Roger looked up suddenly. ‘Why, or else that she didn’t murder her husband at all!’ he said equably.

‘But my dear chap!’ Alec was compelled to protest. ‘How on earth do you make that out?’

Roger folded his arms and fixed an unseeing gaze on the meadow on the other side of the little stream.

‘There’s too much evidence!’ he began in an argumentative voice. ‘A jolly sight too much. It’s all too cut and dried. Now somebody manufactured that evidence, didn’t they? Do you mean to tell me that Mrs Bentley deliberately manufactured it herself?’

‘Well,’ said Alec doubtfully. ‘that’s all very well, but who else could have done.’

‘The real criminal.’

‘But Mrs Bentley being the real criminal—!’

‘Now, look here, Alec, do try and clear your mind of prejudice for the moment. Let’s take it that we’re not sure whether Mrs Bentley is guilty or innocent. No, let’s go a step further and assume for the moment her complete innocence, and argue on that basis. What do we get? That somebody else poisoned Bentley; that this somebody else wished Mrs Bentley not only to be accused of the crime but also, apparently, to suffer for it; and that this somebody therefore laid a careful train of the most convincing and damning evidence to lead to the speedy and complete undoing of Mrs Bentley. Now that gives us something to think about, doesn’t it? And take into consideration at the same time the fact that not only was Mrs Bentley to be disposed of in this way, but Bentley himself as well. In other words, this mysterious unknown had a motive for getting rid of Mr just as much as Mrs Bentley; whether one more than the other we can’t yet say, but certainly both. And the plot was an ingenious one; the very fact of getting rid of the second clears the perpetrator of all suspicion of getting rid of the first, you see. Oh, yes, there’s a lot to think about here.’

‘You’re going too fast,’ Alec complained. ‘What about the evidence?’

‘Yes, the evidence. Well, assuming still that Mrs Bentley is innocent, she’ll have an explanation of some sort for the evidence. But unless I’m very much mistaken, it’s going to be a not particularly convincing one and quite incapable of proof—the mysterious unknown, we know, has quite enough cunning to have made sure of that. In fact we now arrive at a positively delightful anomaly—if Mrs Bentley’s explanations by any chance do carry conviction, I should say she is probably guilty; if they’re feeble and childish, I shall be morally sure of her innocence!’

‘Good Lord, what an extraordinary chap you are!’ Alec groaned. ‘How in the world do you get that?’

‘I should have thought it was quite clear. If they’re feeble and childish, it’ll probably be because they’re true (you’ve no idea how frightfully unconvincing the truth can very often be, my dear Alexander); whereas, if they’re glib and pat, it’ll certainly point to their having been prepared beforehand. Once more I repeat—poisoning is a deliberate and cold-blooded business. The criminal doesn’t leave his explanations to the spur of the moment when the police tap him on the shoulder and ask him what about it; he has it all very carefully worked out in advance, with chapter and verse to support it too. That’s why poisoning trials are always twice as long as those for murder by violence; because there’s so much more difficulty in bringing his guilt home to the criminal. And that, in turn, is not because poison in itself is a more subtle means of murder, but because the kind of person who has recourse to it is, in seven cases out of ten, a careful, painstaking and clever individual. Of course you do get plenty of mentally unbalanced people using it too, like Pritchard or Lamson, but they’re rather the exceptions than the rule. The cold, hard, calculating type, Seddon, Armstrong, that kind of man, is the real natural poisoner. Crippen, by the way, was a poisoner by force of circumstances; but then he’s an exception to every rule that you could possibly formulate. I’m always very sorry for Crippen. If ever a woman deserved murdering, Cora Crippen did, and it’s my opinion that Crippen killed her because he was a coward; she had established a complete tyranny over him, and he simply hadn’t got the moral courage to run away from her. That, and the fact that she had got control of all his savings, of course, as Mr Filson Young has very interestingly pointed out. An extraordinarily absorbing case from the psychological standpoint, Alexander. One day I must go into it with you at the length it deserves.’

‘Lord!’ was Alec’s comment on this first lesson in criminology. ‘How you do gas!’

‘That’s as may be,’ said Roger, and betook himself to his pipe again.

‘Well, what about it all?’ Alec asked a minute or two later. ‘What do you want to do about it?’

Roger paused for a moment. ‘It’s a nice little puzzle, isn’t it?’ he said, more as if speaking his thoughts aloud than answering the other question. ‘It’d be nice to unearth the truth and prove everybody else in the whole blessed country wrong—always providing that there is any more truth to unearth. In any case, it’s a pretty little whetstone to sharpen one’s wits on. Yes.’

‘What do you want to do?’ Alec repeated patiently.

‘Take it up, Alexander!’ Roger replied this time, with an air of briskness. ‘Take it up and pull it about and scrabble into it and generally turn it upside down and shake it till something drops out; that’s what I’ve a jolly good mind to do.’

‘But there’ll be people doing that for her in any case,’ Alec objected. ‘Solicitors and so on. They’ll be looking after her defence, if that’s what you mean.’

‘Yes, that is so, of course. But supposing her solicitors and so on are just as convinced of her guilt as everybody else is. It’s going to be a pretty half-hearted sort of defence in that case, isn’t it? And supposing none of them has the gumption to realise that it’s no good basing their defence just on explanations of the existing evidence—that their client is going to be hanged on that as sure as God made little apples—that if they want to save her they’ve got to dig and ferret out new evidence! Supposing all that, friend Alec.’

‘Well? Supposing it?’

‘Then in that case it seems to me that somebody like us is pretty badly needed. Dash it all, they have detectives to ferret out things for the prosecution, don’t they? Well, why not for the defence? Of course, her solicitors may be clever men; they may be going to do all this and employ detectives off their own bat. But I doubt it, Alexander; I can’t help doubting it very much indeed. Anyhow, that’s what I’m going to be—honorary detective for the defence. I appoint myself on probation, pending confirmation in writing. Now then, Alec—what about coming in with me?’

‘I’m game enough,’ Alec replied without hesitation. ‘When do we start?’

‘Well, let’s see; the assizes come on in about six weeks’ time, I think the paper said. We shall want to get finished at least a fortnight before that. That gives us a month. I don’t think we ought to waste any time. What about pushing off tomorrow morning?’

‘Right-ho! But what I want to know is, what exactly are we going to do?’

‘My dear chap, I haven’t the least idea! Whatever happens to occur to us. We shall have to make a bee-line for Wychford, of course, and the first thing we shall want to know is what the defence is to be. That’s going to take a bit of finding out too, by the way; but I don’t see that we can take up any definite line until we’ve heard Mrs Bentley’s story. I’ll try and hammer out a plan of some kind in the meantime. And Alec!’

‘Yes?’

‘For heaven’s sake do try and give me a little more encouragement over this affair than you did at Layton Court!’

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_91b3b3de-fd64-52e9-b35a-d1e03fd09343)

ARRIVAL AT WYCHFORD (#ulink_91b3b3de-fd64-52e9-b35a-d1e03fd09343)

‘I’VE had one brain-wave at any rate, Alec,’ Roger remarked, settling himself comfortably in the corner of the first-class smoker and hoisting his feet on to the seat opposite.

Alec had just brought the upper part of his body into the carriage after bidding goodbye to a frankly derisive Barbara, and was now lifting their suitcases on to the rack as the train gathered speed—that same half-past ten train, by the way, to which Roger’s attention had been called on the previous morning.

‘Oh?’ he said. ‘What’s that?’

‘Why, the editor of the Daily Courier is by way of being rather a pal of mine. I’m going to call round there on our way through London to ask him if he’ll take me on as unofficial special correspondent.’

‘Are you?’ Alec asked, dropping into his seat. ‘What’s the idea of that?’

‘Well, it occurred to me that we shall be in rather a more favourable position for ramming our way into the heart of things if we’ve got the weight of the Courier behind us than if we just show up as two independent and vulgarly curious gentlemen on their own. The Courier’s name ought to help loosen a hesitating tongue quite a lot. Oh, and by the way, here’s something for you, a list of the important dates in the case that I typed out last night. I’ve got a copy for myself; you can keep that.’

Alec took the paper which Roger was holding out to him and examined it. It was inscribed as follows:

DATES IN THE CASE

‘Thanks,’ said Alec, tucking the paper away in his pocket. ‘Yes, that’ll be useful. Now then, what are you going to do about finding out the lines of Mrs Bentley’s defence, as you said?’

‘Well, I shall take the bull by the horns; go straight to her solicitor, tell him who I am and simply ask him.’

‘Humph!’ said Alec doubtfully. ‘Not likely to get much change there, are you? Not a solicitor who knows his job.’

‘No, none at all. I don’t expect him to tell me for a minute. But I do expect to be able to catch a glimpse of a word or two between the lines. Anyhow, my name ought to be enough to stop them kicking me point-blank out of the door; they will do it politely at any rate. If they ever have heard of me, that is—which I hope and pray!’

‘Yes, there are advantages in being a best-seller, no doubt. How many editions has the latest run through now?’

‘Pamela Alive? Seven, in five weeks. Thanking you kindly. Bought your copy yet?’

The conversation became personal. Very personal.

Arrived at Waterloo a couple of hours later, Roger gave brisk directions. ‘You take the cases along to Charing Cross and put them in the cloakroom, look up a train for Wychford sometime about three o’clock, and then come along and pick me up at the Courier office in Fleet Street. I’m going to get through on the ’phone right away and stop Burgoyne going out to lunch till I’ve seen him, and I’ll wait for you there. Then we can have a spot of lunch at Simpson’s or the Cock, and go on to Charing Cross afterwards. So long!’

They separated on the platform and Roger hurried off to telephone. Burgoyne was in and he made an appointment with him for ten minutes’ time. Jumping into a taxi, he was carried swiftly over Waterloo Bridge and down Fleet Street, arriving in the Great Man’s office with exactly fifteen seconds to spare. Roger rather liked that sort of thing.

It was not Roger’s intention to give any hint, either to Burgoyne himself or to anyone else, of his theory that Mrs Bentley might possibly be the victim of somebody else’s plot rather than the contriver of one of her own making. For one thing it was more of a suspicion than a theory, and his arguments to Alec, interesting though he had made them sound, had been delivered more with the idea of clarifying his own mind on the matter than of stating an actual case. For another thing he preferred, should anything eventually come of this surprising notion, to keep himself the only one in the field. His words to Burgoyne were therefore chosen with some care.

‘This Wychford case,’ he said, when they had shaken hands. ‘Interesting, isn’t it?’

‘It’s been a God-send to us, I can tell you,’ Burgoyne smiled. ‘Carried us all through August, thank heaven. Interesting, is it? Well, I suppose it is in a way. Going to write a book about it, eh?’

‘Well, I might,’ Roger said seriously. ‘At any rate, I want to have a look at it at close quarters. That’s what I’ve come to see you about. You know I’m a keen criminologist, and on top of that the case is simply packed with human interest. Those Allens! There are half a dozen characters down there I’d like to study. Well, what I want to ask you is this. Can I use the Courier’s name as an inducement for them to open their mouths to me? Can you appoint me honorary special correspondent, or something like that? You know I won’t abuse it, and I’d really be awfully grateful.’

But Burgoyne was not editor of the Courier for nothing. He was a wise man.

‘You’ve got something up your sleeve, Sheringham,’ he grinned. ‘I can see that with half an eye. No—don’t trouble to perjure yourself! I see you don’t want to talk about it, so I’m not asking. Yes, you can use the Courier’s name all right. On one condition.’

‘Yes?’ Roger asked, not without apprehension.

‘That if you find out anything (and that’s what I take it you’re really going down for: good lord, man, haven’t I heard you expounding theories on detective-work and the rest of it by the half-mile at a time?)—if you do find out anything, you give us the first option on printing it. At your usual rates, needless to say.’

‘Great Scott, yes—rather! Only too pleased. But don’t expect anything, Burgoyne. I don’t mind admitting that I am going to nose around a bit when I get there, but I’m really only going down out of sheer interest in the case. The psychology—’

‘Write it to me, old man,’ advised Burgoyne. ‘Sorry, but I’m up to the eyes as usual, and you’ve had your two minutes. Don’t mind, do you? That’s all right, then. You chuck our name about as much as you like, and in return you give us first chance on any stuff you write about the case and so on. Good enough. So long, old man; so long.’ And Roger found himself being warmly hand-shaken into the passage outside. There were few people who could deal with Roger, but the editor of the Courier was certainly one of them.

Alec was waiting in the vestibule downstairs, and together they left the building, Roger recounting the success of his mission with considerable jubilation.

‘Yes, that’s going to help us a lot,’ he said, as they marched down Fleet Street. ‘There’s nothing like the hope of seeing your name in a paper like the Courier to make a certain type of person talk. And I have a pretty shrewd idea that both brother William and Mrs Saunderson are just that type, to say nothing of the unpleasant domestic, Mary Blower.’

‘But won’t the Courier have had their own man down there all this time?’

‘Oh, yes; but that doesn’t matter in the least. He won’t have asked the questions that I want to ask. Besides,’ Roger added modestly, ‘there’s another factor in our favour for worming our way into people’s good graces. I hate to keep on reminding you of it, Alexander, but you really are rather inclined to overlook it, you know.’

‘Oh? What’s that?’

‘The fact that I’m Roger Sheringham,’ said that unblushing novelist simply.

Alec’s reply verged regrettably upon crudity. One gathered that Alec was lamentably lacking in a proper respect for his distinguished companion.

‘That’s the worst of making oneself so cheap,’ sighed Roger, as they turned into their destination. ‘If a man is never a hero to his valet, what is he to his fat-headed friends?’

After a thick slab of red steak and a pint of old beer apiece they hailed a taxi and were driven to Charing Cross.

‘Do you know Wychford at all?’ Alec asked when they were seated in the train once again, with a carriage to themselves.

‘Just vaguely. I’ve motored through it, you know.’

‘Um!’

‘Why, do you?’

‘Yes, pretty well. I stayed there for a week once when I was a kid.’

‘Good Lord, why didn’t you tell me that before? You don’t know anybody there, do you?’

‘Yes, I’ve got a cousin living there.’

‘Really, Alec!’ Roger exclaimed with not unjustifiable exasperation. ‘You are the most reticent devil I’ve ever struck. I have to dig things out of you with a pin. Don’t you see how important this is?’

‘No,’ said Alec frankly.

‘Why, your cousin may be able to give us all sorts of useful introductions, besides being able to tell us the local gossip and all sorts of things like that. For goodness’ sake open your mouth and tell me all about it. What sort of a place is Wychford? Does your cousin live in the town itself, or outside it? What can you remember about Wychford?’

Alec considered. ‘Well, it’s a pretty big place, you know. I suppose it’s much the same as any other pretty big place. Lots of sets and cliques and all that sort of thing. My cousin lives pretty well in the middle, in the High Street. She married a doctor there. Nice old house they’ve got, red brick and gables and all that. Just before you get to the pond on the right, coming from London. You remember that pond, at the top of the High Street?’

‘Yes, I think so. Married a doctor, did she? That’s great. We’ll be able to have a look at the medical evidence from the inside, you see, if we want to. What’s the doctor’s name, by the way?’

‘Purefoy. Dr Purefoy. She’s Mrs Purefoy,’ he added helpfully.

‘Yes, I gathered something like that. Not one of the doctors in the case. All right; go on.’

‘Well, that’s about all, isn’t it?’

‘It’s all I shall be able to get out of you, Alec,’ Roger grumbled. ‘That’s quite evident. What taciturn devils you semi-Scotch people are! You’re worse than the real thing.’

‘You ought to be thankful,’ Alec grinned. ‘There’s not much room for the chatty sort when you’re anywhere around, is there?’

‘I disdain to reply to your crude witticisms, Alexander,’ replied Roger with dignity, and went on to reply to them at considerable length.

His harangue was still in full swing when the train stopped at Wychford, and the poorly disguised relief with which Alec hailed their arrival at that station very nearly set him off again. Suppressing with an effort the expression of his feelings, he joined Alec in following the porter with their belongings. They mounted an elderly taxi of almost terrifying instability, and were driven, for a perfectly exorbitant consideration, to the Man of Kent, a hotel which the driver of the elderly taxi was able to recommend with confidence as the best in the town; certainly it was the farthest from the station.

The business of engaging rooms and unpacking their belongings occupied some little time, and Roger ordered tea in the lounge before setting out. Over the meal he expounded the opening of his plan of campaign.

‘There’s nothing like going straight to the fountain-head,’ he said. ‘Nobody in Wychford can tell us so much of what we want to know as Mrs Bentley’s solicitors, so to Mrs Bentley’s solicitors I’m going first of all.’

‘How are you going to find out who they are? Bound to be several solicitors in a place this size.’

‘That simple point,’ Roger said not without pride, ‘I have already attended to. Three minutes’ conversation with the chambermaid gave me the information I wanted.’

‘I see. What do you want me to do? Come with you, or stay here?’

‘Neither. I want you to go and call on your admirable cousin and see if you can wangle an invitation to some meal in the very near future for both of us. Not tea, because I want the husband to be present as well and doctors’ hours for tea are a little uncertain. Don’t say why we’ve come; just tell her that we expect to be here for a few days. You can say that I’ve come to inspect the local Roman remains, if you like.’

‘Are there any Roman remains here?’

‘Not that I know of. But it’s a pretty safe remark. Every town of any size must have Roman remains: its a sort of guarantee of respectability. And use the cunning of the serpent and the guilelessness of a dove. Can I rely on you for that?’

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘Spoken like a Briton!’ approved Roger warmly. ‘And after all, who can do more than that? Answer, almost anybody. But don’t ask me to explain that because—’

‘I won’t!’ said Alec hastily.

Roger looked at his friend with reproach. ‘I think,’ he said in a voice of gentle suffering, ‘that I’ll be getting along now.’

‘So long, then!’ said Alec very heartily.

Roger went.

He was back again in less than half an hour, but it was after six before Alec returned. Roger, smoking his pipe in the lounge with growing impatience, jumped up eagerly as the other’s burly form appeared in the doorway (Alec had got a rugger blue at Oxford for leading the scrum, and he looked it) and waved him over to the corner-table he had secured. The lounge was fairly full by this time, and Roger had been at some pains to keep a table as far away from any other as possible.

‘Well?’ he asked in a low voice as Alec joined him. ‘Any luck?’

‘Yes. Molly wants us to go to dinner there tonight. Just pot-luck, you know.’

‘Good! Well done, Alec.’

‘She seemed quite impressed to hear I was down with you,’ Alec went on with pretended astonishment. ‘In fact, she seems quite keen about meeting you. Extraordinary! I can’t imagine why, can you?’

But Roger was too excited for the moment even to wax facetious. He leaned across the little table with sparkling eyes, making no attempt to conceal his elation.

‘I’ve seen her solicitor!’ he said.

‘Have you? Good. Surely you didn’t get anything out of him, did you?’

‘Didn’t I just! Roger exclaimed softly. ‘I got everything.’

‘Everything?’ repeated Alec startled. ‘Great Scott, how did you manage that?’

‘Oh, no details. Nothing like that. I was only with him for a couple of minutes. He was a dry, precise little man, typical stage solicitor; and he wasn’t giving away if he knew it. Oh, nothing at all. But he didn’t know it, you see, Alexander. He didn’t know it!’

‘What happened, then?’

‘Oh, I told him the same sort of yarn as I told Burgoyne, and asked him point-blank if he could see his way to giving me any information as to whether Mrs Bentley had a complete answer to the charges against her, or not. Of course I had him a bit off his guard, you must remember. It’d be the last thing any solicitor would expect, wouldn’t it? A chap to blow into his office and ask him questions about another client like that. He was a good deal taken aback. In fact he probably thought I was quite mad. In any case, he shut up like a little black oyster, said he regretted he had no information to give me and had me shown out. That’s all that happened.’

‘What do you mean, then? You haven’t found anything out!’

‘Oh, yes, I have,’ Roger returned happily. ‘I’ve found out that we haven’t come down to Wychford in vain. Alec, in spite of his care, that little man gave himself away to me ten times over. There isn’t a shadow of doubt about it—he’s quite sure that Mrs Bentley is guilty!’

CHAPTER V (#ulink_6e8541d3-36b0-58b9-a5d3-d08d222f19e0)

ALL ABOUT ARSENIC (#ulink_6e8541d3-36b0-58b9-a5d3-d08d222f19e0)

FOR a moment Alec looked bewildered. Then he nodded.

‘I see what you’re driving at,’ he said slowly. ‘You mean, if Mrs Bentley’s own solicitor thinks she’s guilty, then her explanation of the evidence can’t be a particularly convincing one?’

‘Exactly.’

‘And according to what you were saying yesterday morning, that makes you yourself still more convinced of her innocence?’

‘Well, don’t put it as strongly as all that. Say that it makes me still more inclined to think she may be innocent.’

‘Contrary to the opinion of everyone else who is most competent to judge. Humph!’ Alec smoked in silence for a minute. ‘Roger, that Layton Court affair hasn’t gone to your head, has it?’

‘How do you mean?’

‘Well, just because you hit on the truth there and nobody else did, you’re not looking on yourself as infallible, are you?’

‘Hit on the truth!’ exclaimed Roger with much pain. ‘After I’d reasoned out every single step in the case and drawn the most brilliant deductions from the most inadequate data! Hit on the truth, indeed!’

‘Well, arrived at the truth, then,’ Alec said patiently. ‘I’m not a word-fancier like you. Anyhow, you haven’t answered my question. You’re not beginning to look on yourself as a story-book detective, and all the rest of the world as the Scotland Yard specimen to match, are you?’

‘No, Alec, I am not,’ Roger replied coldly. ‘The point I made about the unnaturalness of that large quantity of arsenic was a perfectly legitimate one, and I’m only surprised that nobody else seems to have noticed it, instead of promptly drawing the diametrically opposite conclusion. As to whether I’m right or wrong in the explanation I gave you, that remains to be seen; but you’ll kindly remember that I only put it forward as an interesting possibility, not a cast-iron fact, and I merely pointed out that it was just enough to cast a small doubt on the absolute certainty of Mrs Bentley’s guilt.’

‘All right,’ Alec said soothingly. ‘Keep your wool on. What about all that chit-chat about mysterious unknowns?’

Roger affected a slight re-arrangement of his ruffled plumes. ‘There I’m quite ready to admit that I was using my imagination, and plenty of it too. But it was plausible enough for all that. And if Mrs Bentley by any weird chance is innocent it must be true. In any case, isn’t that just what we’re supposed to have come down here to find out?’

‘I suppose it is,’ Alec admitted.

Roger regarded his stolid companion for a moment with a lukewarm eye. Then he broke into a sudden laugh and the plumage was smoothly preened once more.

‘You’re really a bit of an old ass at times, you know, Alec!’

‘So you seem to think,’ Alec agreed, unmoved.

‘Well, aren’t you? Still, never mind that for the moment. The story-book detective has another point to bring forward. It occurred to me while I was thinking over things before you arrived just now. You remember that Mrs Bentley bought those fly-papers they’re making all this fuss about at a local chemist’s here?’

‘Yes?’

‘Well, now, I ask you again—is that natural? Is it natural, if one wants to buy fly-papers for the purpose of extracting the arsenic in order to poison one’s husband, to walk into the local chemist’s where one is perfectly well known and ask for them there? A certain amount of fuss always follows a murder, you know; and nobody realises that better than the would-be murderer. Is it likely that she’d do that, when she could have bought them equally well in London and never have been traced?’

‘That’s a point, certainly. Then you think that she didn’t get them with any—what’s the phrase?—ulterior motive?’

‘To poison her husband with them? Naturally, if she didn’t poison him.’

‘Then what did she get them for?’

‘I don’t know—yet. Would it be too much to suggest that she got them with the idea of killing flies? Anyhow, we must leave that till we’ve discovered her own explanation.’

‘You’re determined to assume her innocence, then?’

‘That, my excellent Alexander,’ said Roger with much patience, ‘is exactly what we have to do. It’s no good even keeping an open mind. If we’re to make any real attempt to do what we’ve come down here for, we’ve got to be prejudiced in favour of Mrs Bentley’s innocence. We’ve got to work on the assumption that she’s being wrongly accused and that somebody else is guilty, and we’ve got to work to bring home the crime to that somebody else. Otherwise our efforts as detectives for the defence are bound to be only half-hearted. You’ve got to lash yourself into a fury of excitement and indignation at the idea of this poor woman, a foreigner and absolutely alone in the country, being unanimously convicted even before her trial when in reality she’s perfectly innocent. That is, if you ever could work up the faintest flicker of excitement about anything, you great fish!’

‘Right-ho!’ Alec returned equably. ‘I’m mad with excitement. I’m bursting with indignation. Let’s go out and kill a policeman.’

‘I admit that it’s a curious position in many ways,’ Roger went on more calmly, ‘but you must agree that it’s a damned interesting one.’

‘I do. That’s why I’m here.’

‘Good. Then we understand each other.’

‘But look here, Roger, ragging aside, there’s one point about the purchase of those fly-papers that I think you’ve overlooked.’

‘Oh? What?’

‘Well—assuming for the moment that she is guilty, did she know that it was going to be recognised as murder? I seem to remember that arsenic poisoning can’t be detected as poisoning, even at a post-mortem, without analysis and all that sort of thing. Wouldn’t she be hoping that the doctors and everybody would think that it was natural death?’