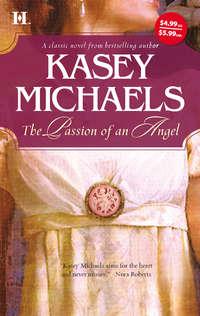

Читать онлайн книгу «The Passion of an Angel» автора Кейси Майклс

The Passion of an Angel

Kasey Michaels

Banning Talbot, Marquess of Daventry and Society's favorite bachelor, is accustomed to having his every whim obeyed–Until he finds himself the reluctant guardian of Prudence MacAfee, the outspoken, golden-haired hoyden laughably nicknamed Angel. Now it's Banning's duty to introduce this deliciously unconventional creature to the ton's most eligible suitors. But his heart has an agenda all its own….

Praise for USA TODAY bestselling author

KASEY MICHAELS

“[A] hilarious spoof of society wedding rituals wrapped around a sensual romance filled with crackling dialogue reminiscent of The Philadelphia Story.”

—Booklist on Everything’s Coming Up Rosie

“A cheerful, lighthearted read.”

—Publishers Weekly on Everything’s Coming Up Rosie

“Michaels continues to entertain readers with the verve of her appealing characters and their exciting predicaments.”

—Booklist on Beware of Virtuous Women

“Lively dialogue and characters make the plot’s suspense and pathos resonate.”

—Publishers Weekly on Beware of Virtuous Women

“A must-read for fans of historical romance and all who appreciate Michaels’ witty and sensuous style.”

—Booklist on The Dangerous Debutante

“Michaels is in her element in her latest historical romance, a tale filled with mystery, sexual tension, and steamy encounters, making this a gem from a true master of the genre.”

—Booklist on A Gentleman by Any Other Name

“Michaels can write everything from a lighthearted romp to a far more serious-themed romance. [Kasey] Michaels has outdone herself.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews, Top Pick, on A Gentleman by Any Other Name

“Nonstop action from start to finish! It seems that author Kasey Michaels does nothing halfway.”

—Huntress Reviews on A Gentleman by Any Other Name

“Michaels has done it again…. Witty dialogue peppers a plot full of delectable details exposing the foibles and follies of the age.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review, on The Butler Did It

“Michaels demonstrates her flair for creating likable protagonists who possess chemistry, charm and a penchant for getting into trouble. In addition, her dialogue and descriptions are full of humor.”

—Publishers Weekly on This Must Be Love

“Kasey Michaels aims for the heart and never misses.”

—New York Times bestselling author Nora Roberts—New York Times bestselling author Nora Roberts

Kasey Michaels

The Passion of an Angel

The Passion of an Angel

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE: COVENANT

BOOK ONE:COMMITMENT

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

BOOK TWO:COMPROMISE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

BOOK THREE:COMMUNION

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

EPILOGUE: HEAVEN-SENT

EPILOGUE

PROLOGUE

COVENANT

There was a sound of revelry by night,

And Belgium’s capital had gather’d then

Her beauty and her chivalry, and bright

The lamps shone o’er fair women and brave men.

A thousand hearts beat happily; and when

Music arose with its voluptuous swell,

Soft eyes look’d love to eyes which spake again,

And all went merry as a marriage bell.

But hush! hark! a deep sound strikes

like a rising knell!

George Noel Gordon,

Lord Byron

Never promise more than you can perform.

Publilius Syrus

“LOOK AT THAT ONE, WOULD YOU, Daventry? Think she’s ripe for the plucking? Ready to lie down in the soft grass outside and give comfort and solace to a soldier about to face the French horde? Or am I totally bosky, and seeing willing beauty in anything in skirts?”

Banning Talbot, Marquess of Daventry, who was more than two parts drunk himself, leaned forward to look in the direction of Colonel Henry MacAfee’s rudely pointing finger. “Harriet Mercer? God’s teeth, man, make your move. Steal a kiss, or more, with my blessings.” Even as he spoke, Miss Mercer could be seen deserting the dance with her red-coated escort, the two of them making for the doorway, and the darkened garden beyond. “Whoops! Yoicks, and away! Pick another one, old man. Lord knows this great barn of a place is packed to the rafters with willing females.”

MacAfee settled his shoulder against the pillar the two men were sharing, having strategically propped themselves alongside the dance floor more than an hour earlier, within good ogling distance of the young ladies going down the dance, and directly in the path the servants had to traverse between the pouring of drinks and the serving of those same libations to Lady Richmond’s thirsty guests. The choice had been a sterling one, as there had been no dearth of either shapely ankles or chilled wine glasses orbiting their small outpost in the midst of what appeared to be a grand celebration of idiots.

Daventry drained his glass, deftly depositing it on a passing tray and scooping up a full one all in one fluid motion. “You know something, MacAfee,” he commented to his friend—if their casual acquaintance of the past three days, combined with their bond of doing their best to drink themselves under the table together, could be considered a basis for friendship, “I’ve been thinking.”

“Never a good thing, thinking,” MacAfee said, sighing in a sorrowful way. “Try not to do it myself. Not with Boney running riot just outside our doors.”

The Marquess smiled, running a hand through the thick, startling silver-on-black mane of hair that looked so out of place above his sparkling green eyes and youthful, unlined face. “But that’s who I’ve been thinking of, MacAfee. Boney. I believe I’ve just now stumbled upon a way to defeat him. We’ll just gather up this lot of sots here, our beloved Iron Duke included, and collectively breathe on the man. Brandy. Port. Wine. Canary. Why, the fumes will be enough to evaporate the man and his entire Old Guard!”

Colonel MacAfee giggled into his wineglass, an action that caused him to inhale a bit of its contents, then snort them out his nose, a trick Daventry considered top-drawer, which only proved he was perhaps a bit too well-to-go for his own good.

Not that he didn’t have good reason to be seeking solace in the bottom of a glass. There was a battle coming, and coming soon. A possible apocalypse, if the rumors running rampant through the ranks were to be believed, with the evil Bonaparte being sent down to ignominious defeat at the hands of the Duke of Wellington, Blücher, and the rest of the allies.

And it would be Wellington, Blücher, and the allies who would take all the credit, garner all the glory, while the foot soldiers, the cavalry, and the junior officers did all the fighting, all the dying. Daventry was heartily sick of war, weary of the bloodshed, the screams, the sacrifice of individual lives in the name of the common good.

If only Bonaparte had been kept on his island. Had it been so bloody difficult to act the jailer to one defeated emperor? Apparently so, or else the man would still be penning wildly abridged histories in his journal rather than mounting an army and marching, even now, on a hastily assembled resistance and its hangers-on of society misses and brainless fops who believed the proper preparation for battle was a whacking good full-dress ball.

“Petticoat alert!” MacAfee exclaimed, nudging Daventry in the ribs as he inclined his head toward a blonde vision just coming down the dance with the Duke of Brunswick. “Hold me back, good milor’. I feel an imminent seduction coming over me.”

The Marquess felt the skin over his cheekbones tightening as he resisted the urge to dash the contents of his glass in the colonel’s leering face, for MacAfee had inadvertently reminded Daventry of the other reason he was finding the wine so irresistible tonight. “The young lady is Miss Althea Broughton, and you will kindly remove your lascivious gaze from her person,” he warned in crushing accents, painfully aware that the word “lascivious” had damn near knotted his tongue. “She is spoken for.”

“But not by you, I’ll wager,” MacAfee said, affably transferring his good-natured leer to a rather lackluster little pudding of a debutante who giggled, then attempted a reproving frown, and lastly blushed to the roots of her tightly curled hair. “Do I sense a story? And more to the point, is it a depressing story? Don’t think I want to hear it if it’s going to bring me down. Low enough, thank you, what with worrying about m’sister.”

“There’s no story, MacAfee,” the marquess said, bowing with exaggerated stiffness as Miss Broughton looked in his direction, then moved on. The beauteous Miss Broughton. The one great love of his life, Miss Broughton. The woman who had two years previously turned his proposal of marriage down flat, Miss Broughton. The woman betrothed these last nine months to a peer so wealthy it took two straining valets to heft his purse into his pocket, Miss Althea Broughton. “And why are you worrying about your sister?” he asked, eager to change the subject, when if the truth were told he couldn’t have cared a fig if MacAfee’s unknown sister was locked in a tower and besieged by fire-breathing dragons.

“Prudence?”

Daventry, who had been watching Miss Broughton’s progress out of the corner of his eye, swiveled his head to the left and repeated, aghast, “Prudence? Would that be a name or an affliction?”

Henry MacAfee grinned—he had a really pleasant grin, actually—and shook his head. “Ghastly name, ain’t it? But she’s the light of my life, Daventry. My Pru. My Angel.” His smile faded abruptly and he took another long drink of his wine. “Poor, innocent baby. It’s criminal how she is forced to live, Daventry. Criminal!”

“I’m sure,” the marquess agreed absently, for his attention was now on the Duke of Wellington, who seemed to be deep in conversation with a subaltern who had just entered the ballroom at a near run, holding his sword as it threatened to swing wide from his waist, which would most certainly have caused the nearby dancers to invent a few new steps to the country dance in progress.

“It’s true, my friend. You have no idea, none at all,” MacAfee continued as a wave of whispers washed across the ballroom. “We’re orphans, you know, and forced to live on the charity of our grandfather, Shadwell MacAfee—and the damndest pinch-penny ever hatched. Not that he’s my guardian, or Pru’s either, now that I’ve reached my majority. Are you listening to me, Daventry? Devil a bit, what’s going on?”

Daventry held up a hand, silencing the colonel. “Listen! Do you hear it? By God, I think the drums are beating to arms! Blücher must have failed!”

MacAfee threw down his glass, which shattered into a thousand pieces at his feet. “No! Not yet! I haven’t come this far just to—Daventry. Daventry!” he repeated, grabbing hold of the marquess’s arm. “Listen to me! If you’re right, if we’re to fight tomorrow, you have to promise me something tonight.”

Daventry watched as the circle of uniforms around Wellington deepened and a few of the ladies, those closest to the Duke, cried out in alarm, two of them swooning into nearby arms. “Not now, MacAfee,” he warned, shaking off the man’s hand as he willed himself back to sobriety. “We have to get to the Place Royale, remember? That’s where all the men have been warned to assemble at the first word of Bonaparte’s march.”

“I said, not yet!” MacAfee nearly shouted, so that Daventry turned to look at the man more closely, seeing the nearly feverish sparkle in the man’s eyes, the ashen gray of his cheeks.

“What is it?” the marquess asked, wondering if the younger man was going to be sick, or break out in tears. After all, he barely knew the fellow. He had laughed with him these past few days, drunk with him, but he didn’t know him. Not really. “Come on, man, you’ve seen battle before this. Think of your men.”

MacAfee shook his head. “I can’t help it, Daventry,” he said, lifting a shaking hand to his forehead. “And I’m not a coward, I swear it. But I have had a dream, a premonition if you will. I’m going to die in this battle, my lord. I have already seen my death.”

“You’ve seen the bottom of too many wineglasses, you mean,” Daventry chided, trying to raise the man’s mood while the musicians attempted to strike up another tune even as the ballroom turned from a small island of enjoyment to a morass of confusion and high emotions. “We’re all afraid.”

“No, no. This is more than fear,” MacAfee said fiercely, reaching into his uniform jacket and extracting a folded paper. “I’m going to die. I’ve even accepted it, save that I didn’t get to bed any of these willing creatures tonight. My only regret is my sister, my little Angel. Leaving a sweet child like her alone with our grandfather? How can I do that and die in peace? And so I have come up with a solution.”

Daventry eyed the unfolded paper with a wary eye. “I’m beginning not to like this, Colonel,” he said quietly, knowing he was honor-bound to listen to the man. That would teach him to drink with near strangers!

“I’ve been watching you these past weeks, Daventry,” MacAfee continued in a rush. “You’re a responsible sort, if a bit stiff—at least until tonight. Make a tolerably pleasant drunk you do, too, not that I haven’t had to help you along a bit, tipping the servants to be sure your glass stayed full as I dangled Miss Broughton under your lovelorn nose. You’ll be a perfect guardian for my Angel. Take the sweet little love under your wing, so to speak. See that she’s financially freed of Shadwell, given a season years from now, when the time is right—all that drivel that’s so important to a female. And she won’t give you a moment’s trouble, I swear it.”

If Daventry hadn’t been sobered by the prospect of the coming battle, MacAfee’s words served to push away the last of the wine-induced fog that blurred his senses. “Allow me a moment to reflect, if you will, MacAfee? You have investigated me these past weeks? You have deliberately sought me out in the last few days, ingratiated yourself to me—and all so that I might take your young sister as my ward if something were to happen to you? And that paper you’re holding? That would be some sort of legal transference of guardianship?”

“Already signed by the Iron Duke himself,” the colonel said, his grin now appearing much more calculating than friendly. “Old Arthur seemed very affected by my concern for my dear little Angel. He also said that you’re the best of men, and plump enough in the pocket since that rich-as-Croesus aunt of yours stuck her spoon in the wall, so that you could take on a half-dozen wards without putting even a small dent in your fortune.”

“I could kill you for this, MacAfee,” Daventry drawled as he took the paper and read it, “except that any such personally satisfying action would definitely saddle me with your unfortunate sibling. And if I don’t agree to sign, I’d be sending a distraught man into battle, wouldn’t I—or at least that’s what Wellington will believe. You’re a singularly vile, clever bastard, Colonel, and I believe I detest you almost as much as I do myself for having fallen prey to your scheme. What’s your sister’s name again? Patience?”

“Prudence,” MacAfee corrected him as he nearly succeeded in pushing Daventry into hysterical laughter by extracting both a pen and a small ink pot from his pocket. “My little Angel. You’ll adore the little mite, truly. And as I said, she won’t give you a moment’s worry. Sweet, biddable, amenable—trust me in this, a true Angel. Just make sure she has an allowance to keep her fed until she’s grown, that’s all I ask. You don’t even have to see her until she’s ready for her season. Just leave her in Sussex for now. Honestly! Then,” he added, pushing the quill at the marquess, “I can die in peace, having served king and country with the last drop of my soldier blood.”

“Oh, cut line, you shameless bastard. And don’t worry your head about dying, MacAfee,” the marquess said, using the colonel’s back as a makeshift desk as he scribbled his name and title at the bottom of the paper. “I don’t intend to let you out of my sight until the battle is over—at which point I shall personally blacken both your eyes and rid you of several of those lying, conniving teeth!”

BOOK ONE

COMMITMENT

Tis true, your budding Miss is very charming,

But shy and awkward at first coming out,

So much alarm’d, that she is quite alarming,

All Giggle, Blush; half Pertness and half Pout;

And glancing at Mamma, for fear there’s harm in

What you, she, it, or they, may be about,

The nursery still leaps out in all they utter—

Besides, they always smell of bread and butter.

George Noel Gordon,

Lord Byron

CHAPTER ONE

Might shake the saintship of an anchorite.

George Noel Gordon,

Lord Byron

“PRUDENCE MACAFEE, Prudence MacAfee,” the Marquess of Daventry grumbled beneath his breath as he reined his mount to a halt on the crest of a small hill that overlooked the MacAfee farm. “Was there ever a more prudish, miss-ish name, or a more reluctant guardian?”

He lifted his curly brimmed beaver to swipe at the sweat caused by the noon heat of this early April day, exposing his silvered black hair to the sun, then turned in the saddle to squint back down the roadway. His traveling coach, containing both his valet, Rexford, and his sister’s borrowed companion, the redoubtable Miss Honoria Prentice, was still not in sight, and he debated whether he should await their arrival or proceed on his own.

Not that either person would be of much use to him. Rexford was an old woman at thirty, too concerned with the condition of his lily-white rump as it was bounced over the spring-rain rutted roads to be a supporting prop to his reluctant-guardian employer. And Miss Prentice, whose pinched-lips countenance could send a delicate child like Prudence MacAfee into a spasm, was probably best not seen until arrangements to transport the young female to London had been settled.

Damn Henry MacAfee for being right! And damn him for so blatantly maneuvering his only-cursory friend into this ridiculous guardianship! He’d heard of the colonel’s bravery in battle, up until nearly the end, when his second horse had been shot out from under him and he had disappeared. If Daventry could have found Henry MacAfee’s body among the heaps of nameless, faceless dead, he would have slapped the man back to life if that were possible. Anything to be shed of this unwanted responsibility.

What was he, Banning Talbot, four and thirty years of age and struggling with this bachelorhood, going to do with an innocent young female? He had asked precisely that question of his sister, Frederica, who had nearly choked on her sherry before imploring her brother to never, ever repeat any such volatile, provocative question in public.

It wasn’t as if he hadn’t already lived up to his commitment. Having been wounded himself at Waterloo, which delayed his return to London only in time to discover that Frederica, his only relative, was gravely ill, the marquess had still met with his solicitor to arrange for a generous allowance to be paid quarterly to one Miss Prudence MacAfee of MacAfee Farm. Contrary to what Henry MacAfee had said, he knew he should at least visit the child, but he buried that thought as he concentrated on taking care of his sister.

He had directed his solicitor to explain the impossibility of Daventry’s presence at the Sussex holding for some time, and had then dragged out that time, beyond his own recovery, beyond any hint of danger remaining in his sister’s condition. Past the Christmas holidays, and beyond.

He would still be in London, enjoying his first full season in two years, if it weren’t that Frederica, who had always been able to draw her older brother firmly round her thumb, had put forth the notion that she would “above all things” adore having a young female in the house whom she could “educate in the ways of society and pamper and dress in pretty clothes.”

Why, Frederica would even pop the girl off, when the time came to put up the child’s hair and push her out into the marriage mart. Her brother, Frederica had promised, would have to do nothing more than host a single ball, present his ward at court, and, of course, foot the bills which “will probably be prodigious, dearest Banning, for I do so adore fripperies.”

It all seemed most logical and personally untaxing, but Daventry still was the one left to beg Grandfather MacAfee to release his granddaughter, and he was the one who would have to face this young girl and explain why he had left this “rescue” of her so late if the grandfather was really the dead loss Henry MacAfee had described to him. But the colonel had said an allowance would be enough to get on with, so the marquess had chosen to ignore his real responsibility—until now.

Daventry jammed his hat back down onto his head, cursed a single time, and urged his mount forward and down the winding path to the run-down looking holding, wondering why he could not quite fight the feeling that he was riding into the jaws of, if not death, great personal danger.

No one came out into the stable yard after he had passed through the broken gate, or even after he had dismounted, leading his horse to a nearby water trough, giving himself time to look more closely at his surroundings, which were depressing as the tepid lemonade at Almack’s.

Daventry already knew that Henry, born of good lineage, had not been all that deep in the pocket, but he had envisioned a small country holding: neat, clean, and genteelly shabby. This place, however, was a shambles, a mess, a totally inappropriate place for any gentle young soul who could earn the affectionate name of “Angel.”

Beginning to feel better about his enforced good deed—rather like a heavenly benefactor about to do a favor for a grateful cherubim—the marquess raised a hand to his mouth and called out, “Hello! Anybody about?”

Several moments later he saw a head pop out from behind the stable door—a door that hung by only two of its three great hinges. The head, that of a remarkable dirty-looking urchin, was rapidly followed by the remainder of a fairly shapeless body clad in what looked to be bloody rags. As a matter of fact, the urchin’s arms were bloodred to the elbows, as if he had been interrupted in the midst of slaughtering a hog.

“I suppose I should be grateful to learn this place is not deserted. I am Daventry,” Banning Talbot said, wondering why he was bothering to introduce himself.

“Daventry, huh?” the youth repeated flatly, and obviously not impressed. “And you’re jolly pleased to be him, no doubt. Now get shed of that fancy jacket, roll up your sleeves, and follow me. Unless you’d rather stand put there, posing in the dirt, while Molly dies?”

The first shock to hit Banning was the bitingly superior tone of the urchin’s voice. The next was its pitch—which was obviously female. Lastly, he was startled to hear the anguished cry of an animal in pain.

He knew in an instant exactly what was afoot.

Leaving sorting out the identity of the rude, inappropriately clad female to later—and while lifting a silent prayer that she couldn’t possibly be who he was beginning to believe she might be, or as old as she looked to be—the marquess stripped off his riding jacket, throwing it over his saddle. “What is it—a breech?” he asked as he tossed his hat away, rolled up his sleeves, and began trotting toward the stable door.

Banning bred horses at Daventry Court, his seat near Leamington, and had long been a hands-on owner, raising the animals as much for his love of them as for any profit involved. The sound of the mare in pain was enough to turn a figurative knife in his gut.

“I’ve been trying to turn the foal,” the female he hoped was not Prudence MacAfee told him as they entered the dark stable and headed for the last stall on the right. “Molly’s already down, and has been for hours—too many hours—but if I hold her head, and talk to her, you should be able to do the trick. I’m Angel, by the way,” she added, sticking out one blood-slick hand as if to give him a formal greeting, then quickly seeming to think better of it. “You took a damned long time in remembering that I’m alive, Daventry, but at least now you might be of some use to me. Let’s move!”

Silently cursing one Colonel Henry MacAfee, who had already gone to his heavenly reward and was probably perched on some silver-lined cloud right now, sipping nectar and laughing at him, Banning forcibly pushed his murderous thoughts to one side as he entered the stall and took in the sight of the obviously frightened, tortured mare. Molly’s great brown eyes were rolling in her head, her belly distorted almost beyond belief, her razor-sharp hooves a danger to both Prudence and himself.

“She’s beginning to give up. We don’t have much time,” he said tersely as he tore off his signet ring and threw it into a mound of straw. “Hold her head tight or we’ll both be kicked to death.”

“I know what to do,” Prudence snapped back at him as she dropped to her knees beside the mare’s head. “I’m just not strong enough to do it all myself, damn it all to blazes!”

And then her tone changed, and her small features softened. She leaned close against Molly’s head, crooning to the mare in a low, singsong voice that had an instantly calming effect on the animal. She had the touch of a natural horsewoman, and Banning took a moment to be impressed before he, too, went to his knees, taking up his position directly behind those dangerous rear hooves.

There was no time to wash off his road dirt, and no need to worry about greasing his arms to make for an easier entry, for there was more than enough blood to make his skin slick as he took a steadying breath and plunged both hands deep inside the mare, almost immediately coming in contact with precisely the wrong end of the foal.

“Sweet Christ!” he exclaimed, pressing one side of his head up against the mare’s rump, every muscle in his body straining as he struggled to turn the foal. His heart pounded, and his breathing grew short and ragged as the heat of the day and the heat and sickening sweet smell of Molly’s blood combined to make him nearly giddy. He could hear Prudence MacAfee crooning to the mare, promising that everything was going to be all right, her voice seemingly coming to him from somewhere far away.

But it wasn’t going to be all right.

Too much blood.

Too little time.

It wasn’t going to work. It simply wasn’t going to work. Not for the mare, who was already too weak to help herself. And if he didn’t get the foal turned quickly, he would have been too late all round.

The thought of failure galvanized Banning, who had never been the sort to show grace in defeat. Redoubling his efforts, and nearly coming to grief when Molly gave out with a halfhearted kick of her left rear leg, he whispered a quick prayer and plunged his arms deeper inside the mare’s twitching body.

“I’ve got him!” he shouted a moment later, relief singing through his body as he gave a mighty pull and watched as his arms reappeared, followed closely by the thin, wet face of the foal he held clasped by its front legs. Molly’s body gave a long, shuddering heave, and the foal slipped completely free of her, landing heavily on Banning’s chest as he fell back on the dirt floor of the stall.

He pushed the foal gently to one side and rose to his knees once more, stripping off his waistcoat and shirt so that he could wipe at the animal’s wet face, urging it to breathe. Swiftly, expertly, he did for the foal what Molly could not do, concentrating his efforts on the animal that still could be saved.

Long, heart-clutching moments later, as the newborn pushed itself erect on its spindly legs, he found himself nose to nose with the foal and looking into two big, unblinking brown eyes that were seeing the world for the first time.

Banning heard a sound, realized it was himself he heard, laughing, and he reached forward to give the animal a smacking great kiss squarely on the white blaze that tore a streak of lightning down the red foal’s narrow face.

“Oh, Molly, you did it! You did it!” he heard Prudence exclaim, and he looked up to see Prudence, still kneeling beside the mare’s head, tears streaming down her dirty cheeks as she smiled widely enough that he believed he could see her perfect molars. “Daventry, you aren’t such a pig after all! My brother wrote that you were the best of his chums, and now I believe him again.”

As praise, it was fairly backhanded, but Banning decided to accept it in the manner it was given, for he was feeling rather good about himself at the moment. He even spared a moment to feel good about Henry MacAfee, who had been thorough enough in his roguery to smooth the way for Prudence’s new guardian.

This pleasant, charitable, all’s well with the world sensation lasted only until the marquess took a good look at Molly, who seemed to be mutely asking his assistance even as Prudence continued to croon in her ear.

I know. I know. But, damn it, Molly, his brain begged silently, don’t look at me that way. Don’t make me believe that you know, too.

“Step away from her, Miss MacAfee,” Banning intoned quietly as the foal, standing more firmly on his feet with every passing moment, nudged at his mother’s flank with his velvety nose. “She has to get up. She has to get up now, or it will be too late.”

Prudence pressed the back of one bloody hand to her mouth, her golden eyes wide in her grimy face. “No,” she said softly, shaking her head with such vehemence that the cloth she had wrapped around her head came free, exposing a long tumble of thick, honey-dark gold hair. “Don’t you say that! She’ll get up. You’ll see. She’ll get up. Oh, please, Molly, please get up!”

Banning understood Prudence’s pain, but he also knew that the mare was already past saving, what was left of her life oozing from her, turning the sweet golden hay she lay in a sticky red. He couldn’t let Prudence, his new charge, fall into pieces now, not when she had been so brave until this point.

“Please leave the stall, Miss MacAfee,” he ordered her quietly, but sternly, already retracing his steps to fetch the pistol from his saddle.

She chased after him, pounding on his back with her small fists, screaming invectives at him that would have done a foot soldier proud, her blows and her words having no impact on him other than to make him feel more weary, more heartsick than he had done when Molly had looked up at him with a single, pleading eye.

He took the long pistol from its specially made holster strapped to his saddle and turned to face his young ward. He didn’t like losing the mare any more than she did, but he had to make her see reason. To do that, he went on the attack. “How old are you?” he asked sharply.

She paused in the act of delivering yet another punch to his person. “Eighteen. I’m eighteen!” she exclaimed after only a slight hesitation, her expression challenging him to treat her as an hysterical child. “Old enough to run this farm, old enough to live on my own, and old enough to decide what to do with my own mare!”

He held out the pistol, which she stared at as if he might shoot her with it. Yet she still stood her ground. He admired her for her courage, but he had to do something that would make her leave.

When he spoke again, it was with the conviction that what he said would serve to make her run away. “All right, Miss MacAfee. Prove it. The mare must be put down. She’s hurting, and she’s slowly bleeding to death, and she shouldn’t be made to suffer any more than she already has. Show me the adult you claim to be. Put Molly out of her pain.”

He didn’t know anyone could cry such great, glistening tears as the ones now running down the girl’s filthy cheeks. He hadn’t known that the sight of a small, quivering chin could make his knees turn to mush even as his heart died inside him.

He found himself caught between wanting to push her to one side and go to the mare and pulling Prudence MacAfee hard against his chest and holding her while she sobbed.

“Oh Christ, I’ll do it,” he said at last, just as she surprised him by raising a shaky hand and trying to grasp the pistol. The sight of their two hands, stained with the blood of the dying mare, each of them clasping one end of the pistol, brought him back to his senses. “I never meant for you to do it. And I’m sorry it has to be done at all. I’m truly, truly sorry.”

“Go to blazes, Daventry,” she shot back, sniffling as she yanked the pistol from his hand and began slowly walking toward the stable, her step slow, her shoulders squared, her chin high. Dressed in her stained breeches, and without the evidence of her long hair to prove the image wrong, she could have been a young man going off to his first battle, terrified that he might show his terror.

“Prudence,” he called after her. “Angel,” he said when she failed to heed him. “You don’t have to do this.”

She kept walking, and he wondered why he didn’t chase after her, wrest the pistol from her hand, and have done with it. But he couldn’t move. He had put down his own horse when he was twelve, a mare he had raised from a foal, and he knew the pain, was familiar with the anguish of doing what was for the best and then living with the result of that fatal mercy. Molly was Prudence’s horse. She was Prudence’s pain.

The stable yard was silent for several minutes, so that when the report of the pistol blasted that silence, Banning flinched in the act of sluicing cold water from the pump over his face and head. His hands stilled as his head remained bowed, and then he went on with his rudimentary ablutions, keeping his head averted as Prudence MacAfee exited the stable, the pistol still in her hand. She returned the spent weapon to him, then placed his signet ring in his hand.

He felt uncomfortable in her presence—stripped to the waist and dripping wet—hardly the competent London gentleman who had come to rescue an innocent child from an uncaring grandparent. He felt useless, no more than an unwelcome intruder, a reluctant witness to a pain so real, so personal, that his intrusion on the scene could almost be considered criminal.

And, with her next words, Prudence MacAfee confirmed that she shared that opinion.

“If you’ll assist me with settling the foal in a clean stall, I would appreciate it, as I can’t seem to get it to move away from…from the body,” she said stonily, and he noticed that her cheeks, although smudged, were now dry, and sadly pale. “And then, my lord Daventry, I would appreciate it even more if you would remount your horse and take yourself the bloody hell out of my life.”

CHAPTER TWO

A mere madness,

to live like a wretch and die rich.

Robert Burton

BANNING SAT BENEATH AN ancient, half-dead tree, his waistcoat and jacket draped over his bare shoulders as he rested his straightened elbows on his bent knees, and watched his traveling coach pull into the stable yard.

The forbidding expression on his lordship’s face gave pause to the driver who had seemed about to venture a comment on his employer’s ramshackle appearance, so that it was left to the valet, Rexford, to explain, within a heartbeat of descending from the coach and rubbing at his afflicted posterior in a surreptitious way, “Milord! You are a shambles!”

“Noticed that, did you? You can’t know how that comforts me, as I’ve always thought you a veritable master of the obvious,” Banning said, remaining where he was as Miss Honoria Prentice joined Rexford in the dirt-packed stable yard, her purse-lipped countenance wordlessly condemning her surroundings and her mistress’s brother, all in one dismissive sweep of her narrowed, watery blue eyes.

“Lady Wendover most distinctly promised me that you had sworn off strong drink since Waterloo, my lord,” Miss Prentice intoned reprovingly as she touched the corners of her thin lips with her ever-present handkerchief. “I see now that she is not as conversant with your vices as she has supposed. Now, where is the child? Heaven help us if she has seen you in this state. Such a shock might scar an innocent infant for life, you know.”

Banning, feeling evil, and more than a little justified in seeking a thimbleful of revenge on his sister’s condemning companion, reached into his pocket, drew out a cheroot, and stuck it, unlit, between his even white teeth. “Miss MacAfee has retired to the house after our brief meeting, Miss Prentice. She rushed off without informing me of her intentions, but I am convinced she is even now ordering tea for her guests, fine young specimen of all the feminine virtues that she is. Why don’t you just trot on up there and introduce yourself? I’d wager she’ll fall on your neck, grateful to see another female.”

“I should imagine so!” Her chin high, her skirts lifted precisely one inch above the dirt of the stable yard, Miss Prentice began the short, uphill trek toward the small, shabby manor house, leaving Rexford behind to hasten to his master’s side, clucking his tongue like a mother hen berating her wandering chick.

“The coachman is even now unloading the valise holding your shirts, my lord, as well as my supply of toiletries. Good God! Is that blood on that rag which was once your second-best shirt? You’ve been fighting, my lord, have you not? I knew it. I just knew it! You were set upon by ruffians, weren’t you? Oh, this vile countryside! If we return to London alive to tell of this horrific journey it will be a miracle!”

“If we can discover a way to travel back to London, dead, to relate our tale, I should be even more astonished, Rexford,” Banning said as he allowed his valet to assist him to his feet and divest him of his waistcoat and jacket for, in truth, he wanted very much to stick his arms into a clean shirt.

“Now stop fussing, if you please,” he ordered, “and restrict yourself to unearthing a clean shirt so that I can present myself at the front door of the house in time to watch our dear Miss Prunes and Prisms Prentice being tossed out on her pointed ear. At the moment, the thought of that scene is the only hope I have of recovering even a small portion of my usual good mood.”

“Sir?” Rexford questioned him, looking up from the opened valise, a fresh neck cloth in his hands. “I don’t understand.”

“Give it a moment, my good man, and you will.”

A few seconds later, as Banning allowed his valet to button his shirt for him, true to his prediction, Miss Honoria Prentice’s tall, painfully thin figure abruptly reappeared on the narrow front porch of the manor house a heartbeat before the echoing slam of the house’s front door reached their ears.

“Ah, dear me, yes,” the marquess breathed almost happily, snatching the neck cloth from Rexford’s hands and tying it haphazardly about his throat, “she’s an angel, all right. Unfortunately, however, I believe she is also one of Lucifer’s own. Come along, my long-suffering companion, we might as well get this over with all in the same afternoon. As I awaited your arrival, I thought I saw some hint of activity just beyond that stand of trees. Let us go and search out this grandfather, this Shadwell, and discover for ourselves what sort of fanciful lies the dear, dead Colonel MacAfee wove about this last member of his family.”

“Over there? Into that stand of trees? With you?” Rexford, who prided himself in never having been farther from London than Richmond Park—and then only this once, and under duress—swallowed hard, his Adam’s apple bobbing up and down above his tightly tied cravat. “There will be bugs, milord. Spiders. Possibly even bees. I do not at all care for insects, milord, as well you know. Better I should remain here, repacking the valise, and praying for a swift remove to the nearest inn.”

Banning looked down his nose at the quivering, shivering valet. “You know, Rexford,” he commented entirely without malice, the unlit cheroot still clamped between his teeth, “if you didn’t possess such a fine hand with the pressing iron, and if the mere thought of finding a suitable replacement were not so fatiguing, I’d dismiss you right now and leave you here to discover your own way back to civilization.”

“Coming right along behind you, milord!” Rexford exclaimed, skipping to catch up with his rapidly striding employer as the two crossed the yard and entered the stand of trees.

The marquess’s eyes had just begun to become accustomed to the shade beneath the cooling canopy of leaves when he found himself stepping out into the sun once more, so that at first he disbelieved what he was seeing. It took Rexford, nearly fainting into his employer’s arms, to convince Banning that his eyes were not deceiving him.

Not that he could be censured for wondering if he had succumbed to hallucination, for the sight that greeted them in the small, round clearing, an area completely encircled by trees, was enough to give any man pause.

There were two people inhabiting the clearing, one of them buried up to his chin in dirt, the other standing nearby, waving flies away from the first with an ancient, bedraggled fan of ostrich plumes. The latter man Banning dismissed as a servant, but the other—with his baldpated, no-eyebrows, gargantuan, bulbous head resembling nothing more than a gigantic maggot with raisin-pudding eyes—commanded his full attention.

“Let me guess,” he drawled, removing the cheroot from his mouth and taking a step closer, then retreating as a vile stench reached his nostrils. “You’d be Mister Shadwell MacAfee, wouldn’t you? And you’re a disciple of dirt baths, I presume—a practice of which I’ve heard, but never before witnessed. Water is an anathema to those who indulge, as I recall, and as my sense of smell verifies. First the Angel who is nothing of the sort, and now the grandfather who is more than described. I’m beginning to believe Colonel Henry MacAfee had a pleasant release, dying in battle.”

“Eh? What? Did someone speak? Hatcher! I told you not to pile the dirt so high. It’s in m’ears, damn your hide, so that now I’m hearing things.” Shadwell MacAfee twisted his large, hairless head from side to side, using his chin to plow a furrow into the dirt in front of him, then looked up at Banning, who grinned and waved down at him. “By God! I’m not hearing things after all. Hatcher! Dig me out! We’ve got company.”

“Hold a moment, Hatcher, if you please,” Banning suggested quickly. “If your employer is as naked under that dirt as I believe him to be, I would consider it a boon if you were to leave him where he is for the nonce. Although we all might consider it a small mercy if you could wave that horsefly away from his nose.”

MacAfee’s cackling laugh brought into evidence the sight of three rotting teeth, all the man seemed to have left in his mouth, and the marquess nodded his silent approval as Rexford moaned a request to vacate the area before he became physically ill, “if it please you that I cast up my accounts elsewhere, milord.”

“You’d be Daventry, wouldn’t you, boy?” MacAfee bellowed in a deep, booming voice once he had done with chortling. “Have to be, seeing as how nobody ever comes here unless they’re forced. Been waiting on your for nearly a year now, you know. Damned decent of you to send that allowance, not that Pru would have known what to do with a groat of it, which is why she hasn’t seen any. Only waste it on what she calls ‘improvements,’ anyways. Bank’s the only place for money, I keep telling her. Put it somewheres where it can grow. Pride m’self on not having spent more’ an hundred pounds a year these past two score and more years. So, you thinking of taking my Pru away?”

Banning believed he could hear the beginnings of a painful ringing in his ears, and he was suddenly thirsty for what would be his first drink of anything more potent than the odd snifter of brandy since Waterloo. “I’d just as soon leave her,” he answered honestly, brutally banishing the memory of those huge, heart-tugging tears he’d witnessed not two hours previously, “but I have promised your late grandson that I would do my possible to care for his sister. As my sister, Lady Wendover, has agreed to give the child a roof over her head until it is time for her Come-out, I have come to collect her, not knowing that she is already grown, and must therefore be whipped into some sort of shape to partake in this particular season. Would you care to give me odds on my sister’s chances of success?”

MacAfee laughed again, and Banning turned his head, reluctant to take another peek into the black cavern of the man’s mouth. MacAfee continued, “I’d as soon place odds on her chances of turning Hatcher here into a coach and four. My wife had the gel to herself for a half-dozen or so years before she kicked off, teachin’ her how to talk and act and the like, but the child’s gone wild since then. Now, go away, Daventry. Been standing in this pit long enough, I have, and it’s time for my man to dig me out. Wouldn’t want any worms taking a fancy to m’bare arse, now would we?”

“Not I, sir,” Banning answered coldly, turning on his heel, already planning to mount a frontal assault on the manor house, believing that, of the two unusual creatures he had encountered in the past hours, Prudence MacAfee seemed far and away the more reasonable of the pair. “After all, being a bit of an angler, I hold some faint affection for earthworms. Good-day, sir.”

PRUDENCE WAS A MASS of conflicting emotions. Sorrow over Molly. Anger over the injustice of it all. Fear caused by the appearance of the man Henry had named as her guardian. Outrage over her childish displays of sorrow, anger, and fear.

How dare the man arrive in the midst of tragedy? How dare he offer his assistance, then utter the damning words that had forced her into taking up that pistol, walking back into Molly’s stall, and…

Who had asked him, anyway? She certainly didn’t want him here, at MacAfee Farm, or anywhere else vaguely connected with her life.

All right, so Henry had picked the man. Picked him with some care, if she had read between the lines of her brother’s explanatory letter to her correctly. Well, wasn’t that above all things wonderful? And she was just supposed to go along with this unexpected change in plans, place herself in this Marquess of Daventry’s “sober, responsible, money-heavy hands?”

When Hell froze and the devil strapped on ice skates! Prudence shouted silently as she stuck her head out the kitchen door—checking to make sure lizard-woman wasn’t hovering somewhere about and ready to spit at her with her forked tongue again—then bounded across the herb garden, on her way to the stable yard once more.

She had bathed in her room, shivering as she stood in a small hip bath and sponged herself with harsh soap and cold water before changing into a clean facsimile of the shirt and breeches she had worn earlier, but she hadn’t done so in order to impress the high-and-mighty Marquess of Daventry.

Indeed, no. She had only done it to remove the sickly sweet stench of Molly’s blood from her person before tending to her mare’s foal. She didn’t care for spit what the marquess thought of her. Some responsible man he was, not so much as sending her a bent penny to live on, and then showing up here at MacAfee Farm, which was the last ting she had ever supposed he would do. Oh yes, Henry had picked himself a sure winner this time, he had. And pigs regularly spun their tails and flew to the moon!

Prudence slipped into the stable, keeping a careful eye on the two men standing beside a traveling coach not twenty yards in the distance, wondering if either one of them had the sense they were born with, to leave the horses in traces like that, and headed for the foal’s stall, armed with a make-shift teat she had loaded with her brother’s recipe for mother’s milk.

“Hello again, Miss MacAfee,” the Marquess of Daventry said from a darkened corner of the stall, and Prudence nearly jumped out of her skin before rounding on the man, a string of curses—more natural to her than any forced pleasantry—issuing, almost unthinkingly, from between her stiff lips.

“Please endeavor to curb this tendency toward profanity, Miss MacAfee,” Banning crooned, pushing himself away from the rough wall of the stall, “allowing me instead to continue to labor under the sweet delusion that you are but an unpolished gem. I had first thought to join you at the house, but quickly decided you would be more likely to show up here. How comforting to know that I am beginning to understand you, if only a little. Now, seeing that I am to be denied any offer of refreshment or other hospitality, perhaps you will favor me with some hint of your agenda? For instance, when will you be ready to depart this lovely oasis of refinement for the barbarity of London?”

Prudence felt her jaw drop, but recovered quickly, brushing past the man to offer the teat to the foal who, thankfully, began feeding greedily. “You actually intend to take me to London?” she asked, looking over her shoulder at the marquess, and wondering how on earth a man with silver hair could look so young. It had to be the eyes. Yes, that was it. Those laughing, mocking green eyes.

“I’d much rather leave you and all memory of this place behind me, but I have given my word to act as your guardian, even though it was wrenched from me under duress. Therefore, Miss MacAfee, yes, I intend for you to remove with me to London, preferably before I have to endure more than one additional interlude with dearest Shadwell.”

Prudence grinned in momentary amusement. “Met m’grandfather, did you? I’d have given my best whip to see that. Was he already in the dirt, or were you unlucky enough to catch him in the buff? He’s a wonder to see, you know. Especially in this last year, once he decided to pluck out all his hair in some new purification ritual he read about somewhere. He’s bald as a shaved peace. Not a single hair left anywhere on his body. No eyebrows, nothing on his brick-thick head, nor on his—”

“You will find, Miss MacAfee,” the marquess broke in just as she was about to do her best to shock him into a fit of apoplexy, “that I do not permit infants the luxury of attempting, however weakly, to make a May game of me. Now if you don’t wish to be turned over my knee, I suggest you dislodge that chip of resentment from your shoulder and give your full attention to impressing me with your finer attributes. I shall give you a moment, so that you may cudgel your brain into discovering at least one redeeming quality about yourself that I might employ to soothe my sister once she recovers from the swoon she will surely suffer the first time you open your mouth in her presence.”

“My brother told me you were a high-stickler,” Prudence grumbled, scratching at an itch on her stomach that could not be denied. “Very well, my lord, I’ll behave. But I won’t like it. I won’t like it above half.”

“Which, you might notice, is neither here nor there to me, Miss MacAfee. Now, when will you be ready to leave? I don’t believe it will take Miss Prentice long to pack up your things, if your current attire is representative of your wardrobe. Freddie will enjoy dressing you from the skin out, or so she told me. I do hope she has sufficient stamina, for she can have no idea of the height and breadth of the consequences of her impulsive commitment.”

“I liked you worlds better when you were helping me with Molly,” Prudence said, pushing her lower lip out in a pout. “Now you sound like some stern, impossibly stuffy schoolmaster, if my brother’s letters from school about his teachers are to be used as a measure of puffed-up consequence. And I go nowhere unless this foal goes with me—and until Molly is taken care of.”

“And what, exactly, do you propose to do with Molly?” the marquess asked, pulling a cheroot from his pocket and sticking it in between his teeth, exactly the way she was wont to jam a juicy bit of straw between hers. He looked very much the London gentleman again, as he had when first she’d seen him, and if he made so much as a single move to put a light to the end of the cheroot while they stood inside the stable, she’d toss a bucket of dirty water all over his urban sophistication.

“I intend to bury her, my lord,” Prudence declared flatly, praying her voice wouldn’t break as she fought back another explosion of tears, “and I shall do so, if it takes me a week to dig the grave.”

“A burial?” Banning Talbot’s grin, when it came, was so unexpected and so downright inspired, that Prudence felt herself hard put to maintain her dislike for him. “Ah, dear Angel, I believe I know precisely the spot, and with our work already about half done for us.”

It didn’t take more than a second for Prudence to deduce his meaning. “Shadwell’s pit?” Her large golden eyes widened appreciably as she contemplated this sacrilege. “He used it today, which means he won’t avail himself of it again until Friday, but—oh, no, it’s a lovely, marvelously naughty thought, and Molly would be sure to like it there, among the trees…but no. I can’t.”

“I’ve been sending you a quarterly allowance since I returned from the continent, Miss MacAfee. A very generous allowance meant to soothe my conscience for not having leapt immediately into a full guardianship. An allowance I understand you have yet to see?”

Prudence breathed deeply a time or two, remembering having to say goodbye to their only household servant save the totally useless Hatcher six months earlier because she could not pay her wages, remembering the leaks in the roof, the “small economies” her grandfather employed that invariably included large sacrifices on her part. Why if she could have afforded to send for the local blacksmith to assist her when Molly had first gone down, the mare might be standing here now, with her foal.

“I saw two men standing beside your traveling coach,” she said, reaching for the shovel she used to muck out the stalls. “If we all dig together, we can have the grave completed by nightfall.”

CHAPTER THREE

Diogenes struck the father

when the son swore.

Robert Burton

THE MARQUESS OF DAVENTRY would have racked up at a country inn if there had been one in the vicinity, but as the single hostelry near MacAfee Farm had burned to the ground some two months previously, and because the marquess had no intention of remaining in the area above a single night, he had dragged a quivering, weeping Rexford into the chamber allotted them by Shadwell MacAfee once the old man had waddled back to the manor house, his huge body swathed in what looked to be a Roman toga.

The chamber could have been worse, Banning supposed—if it had been located in the bowels of a volcano, for instance. Or if the bed had been of nails, rather than the ages-old, rock-hard mattress he had poked at with his fingertips, then sniffed at with his nose before ordering Rexford to take the coach and ride into the village to procure fresh bedding to replace the gray tatters that once, long ago, may have been sheets.

Banning then positioned a chair against the door, as there was no lock and he knew he might be prompted to violence if Miss Prentice barged in during his bath to continue her litany of complaints concerning her own bedchamber, a small box room in the attics, last inhabited by three generations of field mice.

Stripped to the buff, the marquess stood in front of the ancient dressing table, scrubbing himself free of the grime and stench associated with first digging a large pit, then employing an old field gate hitched to his coach horses as a funeral barge for the deceased Molly.

Rexford had, of course, cried off from the actual digging of the grave, citing his frail constitution, his propensity to sneeze when near straw, and his firm declaration that returning to the vicinity of MacAfee’s dirt bath would doubtless reduce him to another debilitating bout of intestinal distress.

That had left Banning, the coachman, Hatcher (who had been bribed into silence and compliance with a single gold piece), and—although he did his best to dissuade her—Miss Prudence MacAfee to act as both grave diggers and witnesses to Molly’s rather ignoble “roll” into the pit and subsequent interment.

Prudence hadn’t shed a single tear, nor spoken a single word, until the last shovelful of dirt had been tamped down, but worked quietly, and rather competently, side by side with the men. Only when Banning had been about to turn away, exhausted by his exertions and badly craving a private interlude with some soap and water, did she falter.

“I’m going to miss you so much, Molly,” he heard her whisper brokenly. “You were my only friend, after my brother. I’ll take good care of your baby, I promise, and I’ll tell him all about you. One day we’ll ride the fields together, and I’ll show him all our favorite places…and let him drink from that fresh stream you liked so well…and…and…oh, Molly, I love you!”

Banning was so affected by this simple speech, this acknowledgment that a horse had been Prudence’s only friend since her brother had died, that he forgot himself to the point of placing an avuncular, comforting arm around the young woman’s shoulders, murmuring, “There, there,” or some such drivel articulate men of the world such as he were invariably reduced to when presented with a weeping female.

The memory of the fact that this sympathetic gesture had earned him a swift punch in the stomach before Prudence ran off across the fields did nothing to improve Banning’s mood as he dressed himself in the clothes Rexford had laid out for him, pushed the chair to one side, and exited his chamber, intent on locating some sort of late supper and his ward, not necessarily in that order.

He walked down the hallway, past the faded, peeling wallpaper, skirting a small collection of pots sitting beneath a damp patch on the ceiling above them, and was just at the stairs when he espied a sliver of light beneath a door just to his left. Already knowing the location of MacAfee’s chamber, Banning deduced that his ward was secreted behind this particular door, probably plotting some way to make his life even more miserable than it was at this moment—if such a feat were actually possible, for the Marquess of Daventry was not a happy man.

His knock ignored, he impatiently counted to ten, then pushed open the door that lacked not only a lock, but a handle as well. He cautiously stepped into the room, on his guard against flying knickknacks, and espied Prudence MacAfee sitting, her back to him, at a small desk pushed up against the single window in the small chamber.

“Love notes from some local swain, I sincerely hope not?” he inquired as he approached the desk to see that she was reading a letter, a fairly thick stack of folded letters at her left elbow. “Freddie has visions of someday making you a spectacular, society-tweaking match with one of the finest families in England. But then, my sister was always one for dreaming.”

Prudence swiftly folded the single page she was reading and slipped it back inside the blue ribbon that held the rest of the letters. “Knocking is then not a part of proper social behavior, my lord?” she asked, turning to him with a sneer marring her rather lovely, golden features. “My late Grandmother MacAfee, who all but beat the social graces into my head until the day she died, would have most vigorously disagreed.”

“I did knock, Miss MacAfee,” he corrected her with a smile, then added, “but as my tutor’s teachings of etiquette did not extend to dealing with bad-tempered, rude termagants foisted upon one by conniving, opportunistic brothers, I then just pushed on, guided more by my inclinations than any notions of what is polite. Now, tell me, if you please. Does anyone in this household eat?”

Prudence opened the top drawer of the small writing desk and slid the packet of letters inside before turning back to Banning, a mischievous grin he had already learned to distrust lighting her features. “Grandfather eats nothing but goat’s milk pudding and mutton, my lord. If you are interested, I am sure Hatcher can serve you in the kitchens. As you may have noticed as you barged into the house, there is no longer any furniture in either the drawing or dining rooms. For myself, I have no appetite tonight, having just buried my horse.”

“You’re enjoying yourself immensely at my expense, aren’t you, Miss MacAfee?” Banning asked, not really needing her to answer. “Perhaps another visit from the redoubtable Miss Prentice is in order. She is most anxious to mount an inspection of your wardrobe before we depart for London in the morning.”

“Let her in here again and I’ll probably shoot her. Besides, I’m not going,” Prudence stated flatly, turning her back on him once more.

Resisting the impulse to grab hold of the young woman by her shoulders and shake her until her teeth rattled, Banning retrained himself enough to utter through his own tightly clenched teeth, “Then, Miss MacAfee, may I presume we may number lying among your other vices? Or was I incorrect in assuming that when you gave me your word you would leave with me after Molly was settled, you were intending to keep true to that word?”

She jumped up from her chair, still most distressingly, disturbingly dressed in a man’s shirt and a patched pair of breeches that clung much too closely to her hips, and rounded on him in a fury.

“You ignorant jackanapes!” she exploded. “Do you really believe I would want to stay here? That anyone with more brains than a doorstop would want to stay here? My God, man, I detest the place! This damned pile is falling down around my ears, I haven’t a penny for repairs to either the house or the land, my grandfather is a mean, miserly, to-let-in-the-attic nincompoop who hasn’t bathed since the day I was able to lock him outside in the rain two years ago. He picks his teeth with a penknife, sleeps on a mattress stuffed with receipts from his deposits in London banks, saves the clippings from his fingers and toes for luck, and bays at full moons. My brother swore he’d get me out of here since the day we first arrived after our parents’ funeral—get us both out of here—and by damn, Daventry, I would have to be a candidate for Bedlam myself to refuse to go. But I can’t. Not yet.”

Banning sat himself down in the chair Prudence had just vacated, pressed his elbows onto the desktop while making a steeple of his fingers, and looked out over the run-down grounds of MacAfee Farm, giving out with an occasional self-depreciating, closemouthed chuckle as he considered all that his new ward had just said.

“It’s the foal, isn’t it, Angel?” he remarked at last, slowly swiveling on the chair to look up at Prudence, who was still standing close beside him, her fists jammed onto her hips, her wild tangle of honey-dark blond hair giving her the appearance of a lioness with her fur ruffled. “You won’t leave without Molly’s foal.”

“Well, you can think! And here I was beginning to believe you were slow, as well as arrogant and supercilious and domineering and—”

“Yes, yes,” Banning interrupted, “I believe we both know how you view me. But remember. I am also your brother’s choice of savior. Thinking back on that evening, I begin to see why he would have traveled to such lengths to insure your future. You and Henry might have been your grandfather’s only heirs, but the scoundrel might live for years and years yet, a prospect Henry—and in his place, I myself—could not look to with much forbearance.”

“My brother escaped to the war,” Prudence told him, her voice soft as she spoke of Henry MacAfee. “He stole the money to buy his commission, sneaking the profit from the sale of the dining room furniture out from under Shadwell’s nose before he could ship it off to the banks. He is going to—was going to send for me once Boney was locked up again. Life here wasn’t easy for either of us, but it was especially difficult for my brother, who was a dozen years older and had known another life more so than had I, for I was still fairly steeped in the nursery when Mama and Papa died in that carriage accident.”

Beginning once more to feel as if he was not quite so put-upon, as if he had actually been selected to do what could only be considered a very good deed, Banning decided there and then that a week—no more—spent at MacAfee Farm couldn’t be considered too great a sacrifice, especially when he thought how he had heartlessly left poor little Prudence MacAfee to suffer here for the better part of a year longer than necessary.

He could make do on the farm for seven short days, long enough for the foal to gain strength and make arrangements for its transport to his stable in Mayfair. Why, he might even enjoy being in the Sussex countryside, as he had been confined to London since returning to England, recovering from his wounds, hovering over his ill sister—and then dancing the night away, gaming with his friends, attending the theater and other such indulgences for several months, he remembered with another fleeting pang of guilt.

Slapping his hands down hard onto his thighs, he rose to his feet, saying, “It’s settled then. I think a week in the country would do both Rexford and Miss Prentice a world of good.”

“I won’t let that lizard near me, you know, so you can ship her off any time it suits you,” Prudence pronounced, preceding Banning to the door. “She slithered in here earlier, to pack for me she said, and left with a flea in her ear after I listened to her going on and on about the fact that I don’t have any gowns. As if I’d be mucking stables in lace and satin! And she’s fair and far out if she thinks I’m going to put up my hair, or let her touch me with those cold white hands as she spits out something about clipping my nails and—”

Banning stopped just inside the doorway, putting out his hands to apply the brakes to Prudence’s tirade before she could grab the bit more firmly between her teeth. “Did you say you don’t own any gowns? Not even one in which to travel to Freddie’s? You’ve nothing but breeches?”

“Oh, close your mouth, Daventry, unless you’ve always longed to catch flies with your tongue. Of course I don’t have any gowns. I was only a child when I came here, and once Grandmother MacAfee was gone, Shadwell decided that my brother’s castoffs were more than sufficient for a growing female. And it’s not as if I go tripping off to church of a Sunday or receive visitors here at MacAfee’s Madhouse, which is what the locals have dubbed the place.”

Banning took a long, assessing look at Prudence as she stood in front of him in the dim candlelight. He had already noticed that her honey-dark hair was thick and lustrous, even if it did look as if she’d trimmed it with a sickle and combed it with a rake. Her huge, tip-tilted eyes, also more honey gold than everyday brown, were far and away her most appealing feature, although her complexion, also golden, and without so much as a single mole or freckle, was not to be scoffed at.

Of average height for a female, with an oval face, small skull, straight white teeth, and pleasantly even features, she might just clean up to advantage. If London held enough soap and water, he added, wishing she didn’t smell quite so much of horse and hay.

There wasn’t much he could tell about her figure beneath the large shirt, although he had already become aware that her lower limbs were straight, her derriere nicely rounded.

“You know something, Angel?” he announced at last, draping a companionable arm around her as they headed for the staircase, just as if she was one of his chums. “I think we’ll go easy on any efforts to coax you out of your cocoon until we’re safely in Mayfair. I wouldn’t want Shadwell to start thinking he’d be giving up an asset he could use to line his pockets.”

“I don’t understand,” Prudence admitted, frowning up at him. “Shadwell’s always said I am worthless.”

“Not on the marriage mart, you’re not,” Banning told her. “Now if we’ve cried friends, perhaps you could find a way to ferret out some food for me and my reluctant entourage before we all fade away, leaving you here alone to face Shadwell’s wrath on Friday when he discovers his dirt bath already occupied.”

“Oh Christ!” Prudence exclaimed, proving yet again that it would take more than a bit of silk and lace to make her close to presentable. “Bugger me if I didn’t forget that. We’ll have to clear out before Friday, won’t we?”

As they reached the bottom of the staircase, Prudence took her guardian’s hand, dragging him toward the kitchen and, he was soon to find out, her secret cache of country ham. “I suppose we could still leave tomorrow, if you find some way to bring Lightning with us.”

“Lightning being Molly’s foal,” Banning said, wondering if he had been born brilliant or had just grown into it. “I supposed it could be managed. My, my, how plans can change in a twinkling. I imagine I shall simply have to endure Rexford’s grateful weeping as we make our way back to London.”

THERE WERE ONLY A FEW things Banning wished to do before he departed for London, chief among them taking a torch to the bed he had tossed and turned in all night, unable to find a spot that did not possess a lump with a talent for digging into his back, but he decided to limit himself to indulging in only one small bit of personally satisfying revenge. He would inform MacAfee that his money supply had been turned off.

Dressed with care by a grumbling but always punctilious Rexford, and with his stomach pleasantly full thanks to Prudence’s offer to share a breakfast of fresh eggs and more country ham out of sight of her grandfather, the marquess took up his cane and set out to locate one Shadwell MacAfee.

Resisting the notion that all he would have to do was to “follow his nose,” Banning inquired his employer’s whereabouts of Hatcher, who was lounging against one peeled-paint post on the porch of the manor house, then set out in the direction the servant had indicated.

He discovered Shadwell sitting cross-legged beneath a tree some thirty yards behind the stable, his lower body draped by a yellowed sheet, his hairless upper body—a mass of folded layers of fat that convinced Banning he would never look at suet pudding in the same way again—exposed to the air. His eyes were closed as he held three oak leaves between his folded-in-prayer hands, and he was mumbling something that, in Banning’s opinion, was most thankfully unintelligible.

“A jewel stuck in your navel might add to the cachet of this little scene, although I doubt you’d spring for the expense, eh Shadwell?” Banning quipped, causing MacAfee to open his black-currant eyes.

“Come to say goodbye, have you, Daventry?” MacAfee asked, beginning to fan himself with the oak leaves. “But not before you poke fun at me, like the rest of them. I’ll outlive them all—you too. Have myself the last laugh. You’ll see. Purification is the answer, the only answer. Dirt baths, meditation, weekly purges. That’s the ticket! I’ll die all right, but not for years and years. And I’ll be rich as Golden Ball while I’m at it. Have everything I own in banks and with the four percenters. Yes, yes. It’ll be me who laughs in the end.”

Banning raised his cane, resting its length on his shoulder. “Dear me, yes, I can see how gratified you are. And all it cost you was the life of your grandson and the affection of your granddaughter. Henry went to war and to his death, to escape you, and Prudence can’t wait to see the back of you as she leaves this place. You’ve a fine legacy, MacAfee. I can see why you must be proud. And what a comfort all that money will be to you in your old age. Or are you planning to have your coffin lined with it?”

“Henry was a wastrel and a dreamer, like his father before him, and gels ain’t worth hen spit on a farm,” MacAfee stated calmly, moving from side to side, readjusting his layers of fat. “This land is no good anymore, Daventry, any fool can see that, even you. And a house is nothing more than a house. It is a man’s body that is his main domicile, his castle. Why, in the teachings of—”

“She’s been allowed to run wild,” Banning interrupted, not wishing to hear a treatise on dirt baths or purgatives. “She’s grown up no more than a hoyden, although at least your wife was with her long enough to give her something of a vocabulary and a sense of what is proper, for which I am grateful—even if the girl delights in her attempts to shock me. She’s lonely, bitter, mildly profane, purposely and most outrageously uncouth—and I lay the blame for all of it at your doorstep, Shadwell.”

“She’s one thing more, Daventry,” MacAfee said, smiling his near-toothless grin. “She’s yours. Now, go away. Hatcher will be arriving shortly with my purgative. I prefer to evacuate any lower intestinal poisons out of doors, you understand.”

Longing to beat the man heavily about the head and shoulders, but adverse to touching him even with his cane, Banning turned on his heel to go, saying only, “I hope you’ve had joy of Prudence’s allowance, for you’ll not see another groat from me.”

“And that’s where you’re wrong, my boy. I will see it every quarter, like clockwork, if you hope for Prudence to inherit any of my considerable wealth,” MacAfee warned, causing Banning to halt in his tracks. “Ah, that stung, didn’t it, Daventry? So upright. So honest. So much the responsible guardian. But you hadn’t thought of that, had you? All that lovely money. It’s up to you now. I’m to cock up my toes someday, as we all must, and worthless little Prudence is now my only heir. Do I leave my lovely blunt, my security, to the chit, or do I give it all over to the Study for Purgative Restoration?”

His grin widened to disgusting dimensions. “What to do, Daventry, what to do?”

“I’ll want your solemn word as a gentleman,” Banning said, hating himself for bowing to the man’s demands but unable to cut Prudence off from funds that rightfully should be hers. “Now, this morning, before I take my leave of this hellhole.”

“Of course, Daventry. You have it,” MacAfee said soothingly as Hatcher appeared, carrying a large jug of some vile-smelling elixir and a single glass. “A small quarterly pittance now against a fortune in the future. It seems fair. Care for a sip? ’Course, I’d recommend unbuttoning your breeches first, as it works quickly.”

Unable to resist impulse any longer, Banning snatched the pitcher from the servant’s hand and dumped its contents over MacAfee’s plucked pate.

Three hours later, her pitifully small satchel of personal belongings tucked up with the luggage, Prudence, wearing her best pair of breeches, climbed into Banning’s traveling coach behind a pinch-lipped Miss Prentice, without so much as turning about for one last look at her childhood home.

CHAPTER FOUR

Ah! happy years!

Once more who would not be a boy?

George Noel Gordon,

Lord Byron

PRUDENCE HEARD THE KNOCK on her door, but ignored it, as she had a half hour earlier; just as she was prepared to ignore it for the remainder of the day.

How could anyone ask her to rise when she was so bloody comfortable? She could not recall ever feeling so clean, or lying against sheets so soft and sweet smelling. How long had it been since she had listened to a gentle rain hitting the windowpane without worrying that the roof might this time cave in on her? At least not since she had been a very young girl.

There was a small fire still burning in the grate across the room, her appetite was still comfortably soothed by the roast beef and pudding she had downed last night when first they had arrived at the inn, and if she felt a niggling urge to avail herself of the chamber pot, well, that could wait as well.

Giving out a soft, satisfied moan, she turned her face more firmly into the pillows and settled down for at least another hour’s sleep, a small smile curving her lips as her naked body sank deeper into the soft mattress….

“Rise and shine, slugabed! The sun’s shining, the air smells fresh as last night’s rain, and I’m in the mood for a picnic. It’s either that or I’ll have to hide out in the common room, away from Rexford’s incessant groaning now that I’ve told him we don’t travel again until tomorrow.”

Prudence sat bolt upright in the bed, clutching the sheets to her breasts, her eyes wide, her ears ringing from the slam of the door against the wall inside her room. “Daventry!” she exclaimed, pushing her badly tangled hair from her eyes and glaring impotently at the idiot who dared barge in on her just as if he were her brother Henry, come to tease her into a morning of adventure. “Are you daft, man? Go away!”

Banning turned around—not before taking just a smidgen more than a cursory peek at her bare back and shoulders, she noticed—and said, a chuckle evident in his voice, “Sleep in the buff, do you? Is this a natural inclination, or wouldn’t Shadwell spring for night rails, either? I suppose I should be grateful you have boots.”

“You’re a pig, Daventry,” Prudence spat out, tugging at the bedspread, pulling its length up and over the sheets in order to drape it around her shoulders. “And consider yourself fortunate I didn’t sleep with my pistol under my pillow, or you’d be spilling your claret all over the carpet now rather than making jokes at my expense.” And then her anger flew away as she leaned forward slightly, asking, “Did you say something about a picnic?”

Still with his back to her, he nodded, saying, “As long as we’re forced to make our progress to London in stages, taking time to find you some proper clothes and allowing Lightning to gather strength, I thought it might be amusing to indulge in a small round of local sight-seeing. I haven’t picnicked since I was little more than a boy, but for some reason I awoke this morning with the nearly irresistible urge to indulge in some simple, bucolic pleasures. However, if you’d rather play the layabout…”

“Give me ten minutes!” Prudence exclaimed, her feet already touching the floor as, the bedspread still around her, she lunged for her breeches. “I’ll meet you downstairs, and we can be off.”