Читать онлайн книгу «A Rose in the Storm» автора Бренда Джойс

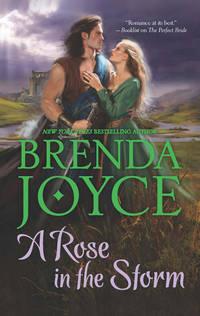

A Rose in the Storm

Brenda Joyce

When rivalry becomes passionWith warfare blazing through Scotland, the fate of the Comyn-MacDougall legacy depends on one woman.Recently orphaned, young Margaret Comyn must secure her clan’s safety through an arranged marriage.But when an enemy invasion puts her at the mercy of the notorious Wolf of Lochaber, her every loyalty and secret want will be challenged.And a kingdom is at stakeLegendary warrior Alexander “the Wolf” MacDonald rides with Robert Bruce to seize the throne of Scotland.But when he takes the fiery Lady Margaret prisoner, she quickly becomes far more than a valuable hostage.For, the passion between them threatens to betray their families, their country…and their hearts."Joyce's tale of the dangers and delights of passion fulfilled will enchant those who like their reads long and rich." Publishers Weekly on The Masquerade

JOIN NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR BRENDA JOYCE FOR AN EPIC STORY OF UNDYING LOVE AND FORBIDDEN DESIRE IN THE HIGHLANDS…

When Rivalry Becomes Passion

With warfare blazing through Scotland, the fate of the Comyn-MacDougall legacy depends on one woman. Recently orphaned, young Margaret Comyn must secure her clan’s safety through an arranged marriage. But when an enemy invasion puts her at the mercy of the notorious Wolf of Lochaber, her every loyalty—and secret want—will be challenged.

And a Kingdom Is at Stake

Legendary warrior Alexander “the Wolf” MacDonald rides with Robert Bruce to seize the throne of Scotland. But when he takes the fiery Lady Margaret prisoner, she quickly becomes far more than a valuable hostage. For the passion between them threatens to betray their families, their country…and their hearts.

Praise for New York Times bestselling author

“As dangerous and intriguing as readers could desire. This is a tale reminiscent of genre classics, with its lush and fascinating historical details and sensuality.”

—RT Book Reviews on Surrender

“Merging depth of history with romance is nothing new for the multitalented author, but here she also brings in an intensity of political history that is both fascinating and detailed.”

—RT Book Reviews on Seduction

“Another first-rate Regency, featuring multidimensional protagonists and sweeping drama… Joyce’s tight plot and vivid cast combine for a romance that’s just about perfect.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review, on The Perfect Bride

“Truly a stirring story with wonderfully etched characters, Joyce’s latest is Regency romance at its best.”

—Booklist on The Perfect Bride

“Romance veteran Joyce brings her keen sense of humor and storytelling prowess to bear on her witty, fully formed characters.”

—Publishers Weekly on A Lady at Last

“Sexual tension crackles…in this sizzling, action-packed adventure.”

—Library Journal on Dark Seduction

A Rose in the Storm

Brenda Joyce

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Contents

CHAPTER ONE (#ud8cd3180-e79f-50d4-b2db-632543efe611)

CHAPTER TWO (#u25d5deb9-6013-594b-b051-6416e4825142)

CHAPTER THREE (#ufb94fee4-c536-5a00-82c9-df12cb02118b)

CHAPTER FOUR (#u24895c07-3e78-5d84-8a43-ec16b6c91f2c)

CHAPTER FIVE (#u85cc705d-0de0-56fe-b28c-6054a66b53c1)

CHAPTER SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

DEAR READER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE

Loch Fyne, the Highlands—February 14, 1306

“IT IS TOO damned quiet.”

Will’s voice cut through the silence of the Highland afternoon, but Margaret did not hear him. Mounted beside him at the head of a column of knights, soldiers and servants, surrounded by the thick Argyll forest, she stared straight ahead.

Castle Fyne rose out of the ragged cliffs and snow-patched hills above them so abruptly that when one rode out of the forest, as they had just done, one had to blink and wonder at the sight, momentarily mistaking it for soaring black rock. But it was a centuries-old stronghold, precariously perched above the frozen loch below, its lower walls stout and thick, its northern towers and battlements jutting into the pale, winter-gray sky. The forest surrounding the loch and the castle was dusted white, and the mountains in the northwest were snowcapped.

Margaret inhaled. She was overcome with emotion—with pride.

And she thought, Castle Fyne is mine.

Once, it had belonged to her mother. Mary MacDougall had been born at Castle Fyne, which had been her dowry in her marriage to William Comyn, which had filled her with great pride. For Castle Fyne was a tremendous prize. Placed on the most western reaches of Argyll, providing a gateway from the Solway Firth, surrounded by lands belonging to Clan Donald and Clan Ruari, the castle had been fought over throughout the centuries. It had been attacked many times, yet it had never once slipped from MacDougall hands.

Margaret trembled, more pride surging within her, for she had adored her mother, and now, the great keep was her dowry, and she would bring it with her in her upcoming marriage. But the anxiety that had afflicted her for the past few weeks, and during this journey, remained. Since the death of her father, she had become the ward of her powerful uncle, John Comyn, the Earl of Buchan. He had recently concluded a union for her. She was betrothed to a renowned knight whom she had never met—Sir Guy de Valence—and he was an Englishman.

“’Tis such a godforsaken place,” her brother said, interrupting her thoughts. But he was glancing warily around. “I don’t like this. It’s too quiet. There are no birds.”

She sat her mare beside Will, her only living brother. Suddenly she wondered at the silence, realizing he was right. There was no rustling of underbrush, either, made by chipmunks and squirrels, or the occasional fox or deer—there was no sound other than the jangle of bridles on their horses, and the occasional snort.

Her tension escalated. “Why is it so quiet?”

“Something has chased the game away,” Will said.

Their gazes met. Her brother was eighteen—a year older than she was—and blond like their father, whom he had been named after. Margaret had been told she resembled Mary—she was petite, her hair more red than gold, her face heart-shaped.

“We should go,” Will said abruptly, gathering up his reins. “Just in case there is more in the hills than wolves.”

Margaret followed suit quickly, glancing up at the castle perched high above them. They would be within the safety of its walls in minutes. But before she could urge her mare forward, she recalled the castle in the springtime, with blue and purple wildflowers blooming beneath its walls. And she remembered skipping about the flowers, where a brook bubbled and deer grazed. She smiled, recalling her mother’s soft voice as she called her inside. And her handsome father striding into the hall, his mantle sweeping about him, spurs jangling, her four brothers behind him, everyone exhilarated and speaking at once....

She blinked back tears. How she missed her father, her brothers and her beloved mother. How she cherished her legacy now. And how pleased Mary would be, to know that her daughter had returned to Loch Fyne.

But her mother had despised and feared the English. Her family had been at war with the English all her life, only recently coming to a truce. What would Mary think of Margaret’s arranged marriage to an Englishman?

She turned to face William, discomfited by her emotions, and in so doing, glanced back at the sixty men and women in the cavalcade behind them. It had been a difficult journey, due mostly to the cold winter and the snow, and she knew that the soldiers and servants were eager to reach the castle. She had not visited the stronghold in a good ten years, and she was eager to reach its warm halls, too. But not just to revisit her few memories. She was worried about her people. Several servants had already complained of frozen fingers and toes.

She would tend them immediately, once they reached the great keep, just as she had seen her mother do.

But the anxiety that had afflicted her for the past few weeks would not go away. She could not pretend that she was not worried about her impending marriage. She meant to be grateful. She knew she was fortunate. Her uncle controlled most of the north of Scotland, his affairs were vast, and he could have simply ignored her circumstances once both her parents had passed. He could have kept her at his home, Balvenie, in some remote tower, and established his own steward at Castle Fyne. He could have sent her to Castle Bain, which William had inherited from their father. Instead, he had decided upon an advantageous political union—one that would elevate her status, as well as serve the great Comyn family.

But another pang went through her as she walked her mare forward on the narrow path leading up to the castle. Her uncle Buchan also despised the English—until this truce, he had warred against them for years. The sudden allegiance made her uneasy.

“I think Castle Fyne is beautiful,” she said, hoping she sounded calm and sensible. “Even if it has come to some neglect since Mother’s death.” She would repair every rotten timber, every chipped stone.

“You would.” William grimaced and shook his head. “You are so much like our mother.”

Margaret considered that high flattery, indeed. “Mother always loved this place. If she could have resided here, and not at Bain with Father, she would have.”

“Mother was a MacDougall when she married our father, and she was a MacDougall when she died,” William said, somewhat impatiently. “She had a natural affinity for this land, much like you. Still, you are a Comyn first, and Bain suits you far more than this pile of rock and stone—even if we need it to defend our borders.” He studied her seriously. “I still cannot fathom why you wished to come here. Buchan could have sent anyone. I could have come without you.”

“When our uncle decided upon this union, I felt the need to come here. Perhaps just to see it for myself, through a woman’s eyes, not a child’s.” She did not add that she had wanted to return to Castle Fyne ever since their mother had died a year and a half ago.

Margaret had grown up in a time of constant war. She could not even count the times the English King Edward had invaded Scotland during her lifetime, or the number of rebellions and revolts waged by men like Andrew Moray, William Wallace and Robert Bruce. Three of her brothers had died fighting the English—Roger at Falkirk, Thomas at the battle of River Cree and Donald in the massacre at Stirling Castle.

Their mother had taken a silly cold after Donald’s death. The cough had gotten worse and worse, a fever had joined it, and she had never recovered. That summer, she had simply passed on.

Margaret knew their mother had lost her will to live after the death of three of her sons. And her husband had loved her so much that he had not been able to go on without her. Six weeks later, on a red-and-gold autumn day, their father had gone hunting. He had broken his neck falling from his horse while chasing a stag. Margaret believed he had been deliberately reckless—that he had not cared whether he lived or died.

“At least we are at peace now,” she said into the strained silence.

“Are we?” Will asked, almost rudely. “There was no choice but to sue for peace, after the massacre at Stirling Castle. As Buchan said, we must prove our loyalty to King Edward now.” His eyes blazed. “And so he has tossed you off to an Englishman.”

“It is a good alliance,” Margaret pointed out. It was true her uncle Buchan had warred against King Edward for years, but during this time of truce, he wished to protect the family by forging such an allegiance.

“Oh, yes, it is an excellent alliance! You will become a part of a great English family! Sir Guy is Aymer de Valence’s bastard brother, and Aymer not only has the ear of the king, he will probably be the next Lord Lieutenant of Scotland. How clever Buchan is.”

“Why are you doing this, now?” she cried, shaken. “I have a duty to our family, Will, and I am Buchan’s ward! Surely, you do not wish for me to object?”

“Yes, I want you to object! English soldiers killed our brothers.”

Will had always had a temper. He was not the most rational of young men. “If I can serve our family in this time of peace, I intend to do so,” she said. “I will hardly be the first woman to marry a rival for political reasons.”

“Ah, so you finally admit that Sir Guy is a rival?”

“I am trying to do my duty, Will. There is peace in the land, now. And Sir Guy will be able to fortify and defend Castle Fyne—we will be able to keep our position here in Argyll.”

He snorted. “And if you were ordered to the gallows? Would you meekly go?”

Her tension increased. Of course she would not meekly go to the gallows—and initially, she had actually considered approaching her uncle and attempting to dissuade him from this course. But no woman in her position would ever do such a thing. The notion was insane. Buchan would not care for her opinion, and he would be furious with her.

Besides, so many Scots had lost their titles and lands in the years before the recent peace, forfeited to the Crown, to be given to King Edward’s allies. Buchan had not lost a single keep. Instead, he was marrying his niece to a great English knight. If a bargain had been made, it was a good one—for everyone, including herself.

“So, Meg—what will you do if after you are married, Sir Guy thinks to keep you at his estate in Liddesdale?”

Margaret felt her heart lurch. She had been born at Castle Bain in the midst of Buchan territory. Nestled amidst the great forests there, Castle Bain was her father’s birthright and her home. Their family had also spent a great deal of time at Balvenie, the magnificent stronghold just to the east where Buchan so often resided.

Both of those Comyn castles were very different from Castle Fyne, but they were all as Scottish as the Highland air she was now breathing. The forests were thick and impenetrable. The mountains were craggy, peaks soaring. The lochs below were stunning in their serenity. The skies were vividly blue, and no matter the time of year, the winds were brisk and chilling.

Liddesdale was in the borderlands—it was practically the north of England. It was a flat land filled with villages, farms and pastures. Upon being knighted, Sir Guy had been awarded a manor there.

She could not imagine residing in England. She did not even wish to consider it. “I would attempt to join him when he visited Castle Fyne. In time, he will be awarded other estates, I think. Mayhap I will be allowed to attend all of his lands.”

William gave her a penetrating look. “You may be a woman, Meg, and you may pretend to be dutiful, but we both know you are exactly like Mother in one single way—you are stubborn, when so moved. You will never settle in England.”

Margaret flushed. She did not consider herself stubborn. She considered herself gentle and kind. “I will cross that bridge when I come to it. I have great hopes for this union.”

“I think you are as angry about it as I am, and as afraid. I also think you are pretending to be pleased.”

“I am pleased,” she said, a bit sharply. “Why are you pressing me this way, now? June is but a few months away! I have come here to restore the keep, so it is somewhat pleasing when Sir Guy first sees it. Do you hope to dismay me?”

“No—I do not want to distress you. But I have tried to discuss this handfast several times—and you change the subject or run away. Damn it. I have many doubts about this union, and knowing you as well as I do, I know you are afraid, too.” He said softly, “And we only have each other now.”

He was right. If she dared be entirely honest with herself, she was worried, dismayed and afraid. But she then looked away.

“He may be English but he is a good man, and he has been knighted for his service to the king.” She was echoing her uncle now. “I was told he is handsome, too.” She could not smile, although she wished to. “He is eager for this union, Will, and surely that is a good sign.” When he simply stared, she added, “My marriage will not change our relationship.”

“Of course it will,” William said flatly. “What will you do when this peace fails?”

Margaret tried not to allow any dread to arise. “Our uncle does not think this peace will fail,” she finally said. “To make such a marriage, he must surely believe it will endure.”

“No one thinks it will endure!” William cursed. “You are a pawn, Meg, so he can keep his lands, when so many of us have had our lands and titles forfeited for our so-called treason! Father would never have allowed this marriage!”

Again, William was right. “Buchan is our lord now. I do not want him to lose his lands, Will.”

“Nor do I! Didn’t you overhear our uncle and Red John last week, when they spent an hour cursing Edward, swearing to overthrow the English—vowing revenge for William Wallace!”

Margaret felt ill. She had been seated in a corner of the hall with Isabella, Buchan’s pretty young wife, sewing. She had deliberately eavesdropped—and she had heard their every word.

How she wished she had not. The great barons of Scotland were furious with the humiliation King Edward had delivered upon them by stripping all her powers—she would now be ruled by an Englishman, an appointee of King Edward’s. There were fines and taxes being levied upon every yeoman, farmer and noble. She would now be taxed to pay for England’s wars with France and the other foreign powers he battled with. He would even force the Scots to serve in his armies.

But the coup de grâce had been the brutal execution of William Wallace. He had been dragged by horse, hanged, cut down while still alive, disemboweled and beheaded.

Every Scot, whether Highlander or lowlander, prince or pauper, baron or farmer, was stricken by the barbaric execution of the brave Scottish rebel. Every Scot wanted revenge.

“Of course my marriage was made for politics,” she said, aware that her voice sounded strained. “No one marries for affection. I expected a political alliance. We are allies of the Crown now.”

“I did not say you should have a love match. But our uncle is hardly an ally of King Edward’s! This is beyond politics. He is throwing you away.”

Margaret would never admit to him that if she dared think about it, she might feel just that way—as if she had been thoughtlessly and carelessly used by her uncle for his own ends—as if she had been casually tossed away, to serve him in this singular moment before his loyalties changed again. “I wish to do my part, Will. I want to keep the family strong and safe.”

William moved his horse close, lowering his voice. “He hardly has a claim, but I think Red John will seek the throne, if not for himself, then perhaps for King Balliol’s son.”

Margaret’s eyes widened. Red John Comyn, the Lord of Badenoch, was chief of the entire Comyn family, and lord even over Buchan. He was like another uncle to her—but truly he was a very distant cousin. Her brother’s words did not surprise her—she had overheard such speculation before—but now she realized that if Red John sought the throne, or attempted to put the former Scottish King John Balliol’s boy Edward upon it, Buchan would support him, leaving her married to an Englishman and on the other side of the great war that would surely ensue.

“Those are rumors,” she said.

“Yes, they are. And everyone knows that Robert Bruce still has his eye upon the Scottish throne,” William said with some bitterness. The Comyns hated Robert Bruce, just as they had hated his father, Annandale.

Margaret was becoming frightened. If Red John sought the throne—if Robert Bruce did—there would be another war, she felt certain. And she would be on the opposite side as an Englishman’s wife. “We must pray for this peace to hold.”

“It will never hold. I am going to lose you, too.”

She was taken aback. “I am getting married, not going to the Tower or the gallows. You will not lose me.”

“So tell me, Meg, when there is war, if you become loyal to him—to Sir Guy and Aymer de Valence—how will you be loyal to me?” His expression one of revulsion and anger, William spurred his gelding ahead of her.

Margaret felt as if he had struck her in the chest. She kicked her mare forward, hurrying after him, aware that he wasn’t as angry as he was afraid.

But she was afraid, too. If there was another war, her loyalty was going to be put to a terrible test. And sooner or later, there would be another war—she simply knew it. Peace never lasted, not in Scotland.

Dismay overcame her. Could she be loyal to her family and her new husband? And if so, how? Wouldn’t she have to put her new husband first?

Her gaze had become moist. She lifted her chin and squared her shoulders, reminding herself that she was a grown woman, a Comyn and a MacDougall, and she had a duty to her family now—and to herself. “We will never be enemies, Will.”

He glanced back at her grimly. “We had better pray that something arises to disrupt your marriage, Meg.”

Suddenly Sir Ranald, one of Buchan’s young knights—a handsome freckled Scot of about twenty-five—rode up to them. “William! Sir Neil thinks he has seen a watch in the trees atop the hill!”

Margaret’s heart lurched with a new fear as William paled and cursed. “I knew it was too damn quiet! Is he certain?”

“He is almost certain—and a watch would scare the wildlife away.”

Sir Ranald had ridden in front of them, blocking their way, and they had stopped on the narrow path. Margaret now realized that the forest surrounding them wasn’t just quiet, it was unnaturally silent—unnervingly so.

“Who would be watching us?” Margaret whispered harshly. But she did not have to ask—she knew.

MacDonald land was just beyond the ridge they rode below.

Margaret looked at Sir Ranald, who returned her gaze, his grim. “Who else but a MacDonald?”

Margaret shivered. The enmity between her mother’s family and the MacDonald clan went back hundreds of years. The son of Angus Mor, Alexander Og—known as Alasdair—was Lord of Islay, and his brother Angus Og was Lord of Kintyre. The bastard brother, Alexander MacDonald, was known as the Wolf of Lochaber. The MacDougalls had been warring against the MacDonalds over lands in Argyll for years.

She looked up at the forest-clad hillside. She saw nothing and no one in the snowy firs above.

“We only have a force of fifty men,” Will said grimly. “But there are four dozen men garrisoned at the castle—or so we think.”

“Let’s hope that Sir Neil saw a hunter from a hunting party,” Sir Ranald said. “Master William, you and your sister need to be behind the castle walls as soon as possible.”

William nodded, glancing at Margaret. “We should ride immediately for the keep.”

They were in danger, for if the MacDonald brothers meant to attack, they would do so with far more than fifty men. Margaret glanced fearfully around. Not even a branch was moving on the hillside. “Let us go,” she agreed.

Sir Ranald stood in his stirrups, half turning to face the riders and wagons below. He held up his hand and flagged the cavalcade forward.

Will spurred his bay stallion into a trot, and Margaret followed.

* * *

IT REMAINED ABSOLUTELY silent as their cavalcade passed through the barbican, approaching the raised drawbridge before the entry tower. Margaret was afraid to speak, wondering at the continuing silence, for word had been sent ahead by messenger, declaring their intention to arrive. Of course, messages could be intercepted, and messengers could be waylaid—even though the land was supposedly at “peace.” But then heads began popping up on the ramparts of the castle walls, adjacent the gatehouse. And then murmurs and whispers could be heard.

“’Tis Buchan’s nephew and niece....”

“’Tis Lady Margaret and Master William Comyn....”

Their cavalcade had halted, most of it wedged into the barbican. Sir Ranald cupped his hands and shouted up at the tower, to whomever was on watch there. “I am Sir Ranald of Kilfinnan, and I have in my keeping Lady Margaret Comyn and her brother, Master William. Lower the bridge for your mistress.”

Whispers sounded from the ramparts. The great drawbridge groaned as it was lowered. Margaret saw some children appear on the battlements above, as she gazed around, suddenly making eye contact with an older woman close to the entry tower. The woman’s eyes widened; instinctively, Margaret smiled.

“’Tis Lady Mary’s daughter!” the old woman cried.

“’Tis Mary MacDougall’s daughter!” another man cried, with more excitement.

“Mary MacDougall’s daughter!” others cried.

Margaret felt her heart skid wildly when she realized what was happening—these good folk remembered her mother, their mistress, whom they had revered and loved, and she was being welcomed by them all now. Her vision blurred.

These were her kin. These were her people, just as Castle Fyne was hers. They were welcoming her, and in return, she must see to their welfare and safety, for she was their lady now.

She smiled again, blinking back the tears. From the ramparts, someone cheered. More cheers followed.

Sir Ranald grinned at her. “Welcome to Castle Fyne, Lady,” he teased.

She quickly wiped her eyes and recovered her composure. “I had forgotten how much they adored my mother. Now I remember that they greeted her this way, with a great fanfare, when I was a child, when she returned here.”

“She was a great lady, so I am not surprised,” Sir Ranald said. “Everyone loved Lady Mary.”

William touched her elbow. “Wave,” he said softly.

She was startled, but she lifted her hand tentatively and the crowd on the ramparts and battlements and in the entry tower roared with approval. Margaret was taken aback. She felt herself flush. “I am hardly a queen.”

“No, but this is your dowry and you are their mistress.” William smiled at her. “And they have not had a lady of the manor in years.”

He gestured, indicating that she should precede him, and lead the way over the drawbridge into the courtyard. Margaret was surprised, and she looked at Sir Ranald, expecting him to lead the way. He grinned again, with a dimple, and then deferentially bowed his head. “After you, Lady Margaret,” he said.

Margaret nudged her mare forward, the crowd cheering again as she crossed the drawbridge and entered the courtyard. She felt her heart turn over hard. She halted her mare and dismounted before the wooden steps leading up to the great hall’s front entrance. As she did, the door opened and several men hurried out, a tall, gray-haired Scot leading the way.

“Lady Margaret, we have been expecting ye,” he said, beaming. “I am Malcolm MacDougall, yer mother’s cousin many times removed, and steward of this keep.”

He was clad only in the traditional linen leine most Highlanders wore, with knee-high boots and a sword hanging from his belt. Although bare-legged, and without a plaid, he clearly did not mind the cold as he came down the steps and dropped to one knee before her. “My lady,” he said with deference. “I hereby vow my allegiance and my loyalty to you above all others.”

She took a deep breath, trembling. “Thank you for your oath of fealty.”

He stood, his gaze now on her face. “Ye look so much like yer mother!” He then turned to introduce her to his two sons, both young, handsome men just a bit older than she was. Both young men swore their loyalty, as well.

William and Sir Ranald had come forward, and more greetings were exchanged. Sir Ranald then excused himself to help Sir Neil garrison their men. William stepped aside with him, and Margaret was distracted, instantly wanting to know what they were discussing, as they were deliberately out of her earshot.

“Ye must be tired,” Malcolm said to her. “Can I show ye to yer chamber?”

Margaret glanced at William—still in a serious and hushed conversation. She felt certain they were discussing the possibility of an enemy scout having been on the hillside above them, watching their movements. “I am tired, but I do not want to go to my chamber just yet. Malcolm, has there been any sign of discord around Loch Fyne lately?”

His eyes widened. “If ye mean have we skirmished with our neighbors, of course we have. One of the MacRuari lads raided our cattle last week—we lost three cows. They are as bold as pirates, using the high seas to come and go as they please! And the day after, my sons found a MacDonald scout just to the east, spying on us. It has been some time, months, truly, since we have seen any MacDonald here.”

She felt herself stiffen. “How do you know that it was a scout from clan Donald?”

Malcolm smiled grimly. “We questioned him rather thoroughly before we let him go.”

She did not like the sound of that, and she shivered.

He touched her arm. “Let me take ye inside, lady, it’s far too cold fer ye to be standing here on such a day, when we have so little sun.”

Margaret nodded, as William returned to her side. She gave him a questioning look but he ignored her, gesturing that she follow Malcolm up the stairs. Disappointed, she complied.

The great hall at the top of the stairs was a large stone chamber with high, raftered ceiling, a huge fireplace on one wall. A few arrow slits let in some scant light. Two large trestle tables were centered in the room, benches on their sides, and three carved chairs with cushioned seats sat before the hearth. Pallets for sleeping were stacked up against the far walls. A large tapestry of a battle scene completed the room, hanging on the center wall.

Margaret sniffed appreciatively. The rushes were fresh and scented with lavender oil. And suddenly she smiled—remembering that the hall had smelled of lavender when she had last been present as a child.

Malcolm smiled. “Lady Mary insisted upon fresh rushes every third day, and she especially liked the lavender. We hoped you would like it, too.”

“Thank you,” Margaret said, moved. “I do.”

The servants they had brought with them were now busy bringing their personal belongings, which filled several large chests, into the hall. Margaret espied her lady’s maid, Peg, who was three years older than she was and married to one of Buchan’s archers. She had known Peg for most of her life, and they were good friends. Margaret excused herself and hurried over to her. “Are you freezing?” she asked, taking her cold hands in hers. “How are your blisters?” She was concerned.

“Ye know how I hate the cold!” Peg exclaimed, shivering. She was as tall and voluptuous as Margaret was slender and petite, with dark auburn hair. She wore a heavy wool plaid over her ankle-length leine, but she was shivering anyway. “Of course I am freezing, and it has been a very long journey, too long, if ye ask me!”

“But we have arrived, and safely—no easy feat,” Margaret pointed out.

“Of course we arrived safely—there is no one at war now,” Peg scoffed. Then, “Margaret, yer hands are ice cold! I knew we should have made camp earlier! Yer frozen to the bone, just as I am!”

“I was cold earlier, but I am not frozen to the bone, and I am so pleased to be here.” Margaret looked around the hall again. She almost expected her mother to appear from an empty doorway, smiling at her as she entered the room.

She then shook herself free of such a fanciful thought. But she had never missed her more.

“I am going to light a fire in yer room,” Peg said firmly. “We cannot have ye catching an ague before ye marry yer English knight.”

Margaret met her steadfast gaze grimly. From her tone, she knew that Peg hoped she would catch a cold and be incapable of attending her own June wedding.

She did not fault her. Peg was a true Scotswoman. She hated the MacDonalds and several other rival clans, but she also hated the English bitterly. She had been aghast when she had learned of Margaret’s betrothal. Being outspoken, she had ranted and raved for some time, until Margaret had had to command her to keep her tongue.

While they were in some agreement on the subject of her wedding, Peg’s opinions simply did not help.

“I believe my mother’s chamber is directly atop the stairwell,” Margaret said. “I think that is a good idea. Why don’t you make a fire and prepare the room. And then see to supper.”

Margaret wasn’t hungry, but she wanted to wander about her mother’s home with some privacy. She watched Peg hurry away to harangue a young lad who was in charge of her chest. As they started for the stairwell leading to the north tower where her chamber was, Margaret followed.

Because the keep was so old, the ceiling was low, so low most men had to go up the stairwell hunched over. Margaret did not have to duck her head, and she went past the second landing, where her chamber was. She glanced inside as she did so, noticing the open shutters on a single window, the heavy wooden bed, and her chest, brought with them from Balvenie. Peg was already inspecting the hearth. Margaret quickly continued up the stairs, before her maid might object. The third level opened onto the ramparts.

Margaret left the tower, walking over to the crenellated wall. It was frigidly cold now, as the afternoon was late, the sun dull in an already cloudy sky. She pulled her dark red mantle closer.

The views were magnificent from where she now stood. The loch below the castle was crusted with thick ice near the shore, but the center was not frozen, and she knew that the bravest sailors might still attempt to traverse it, and often did, even in the midst of winter. The far shore seemed to be nothing but heavy forest.

She glanced south, at the path they had taken up to the keep. It was narrow and steep, winding up the hillside, the loch below it. From where she stood, she could see the adjacent glen. A wind was shifting the huge trees in the forest there.

It was breathtaking, beautiful. She wrapped her arms around herself, suddenly fiercely glad that she had come to Castle Fyne, even if it was on the eve of her marriage to an Englishman.

Then she stared at the glen below more sharply— it was as if the forest were moving, a solid phalanx of trees marching, up the hill, toward the castle.

A bell above her began to toll. Margaret stiffened. There was no mistaking the shrill warning sound. And suddenly there were racing footsteps behind her, going past her. Men began rushing from the tower she had just left, bows over their shoulders, slings filled with arrows. They ran to take up defensive positions upon the castle’s walls!

Margaret cried out, leaning over the ramparts, staring at the thickly forested glen—and at the army moving through it.

“Margaret! Lady Margaret!”

Someone was shouting for her from within. She could not move or respond. She was in disbelief, and the bells were shrieking madly above her.

Her heart lurched with sickening force. The forest wasn’t marching toward her—it was hundreds of men, an army, carrying huge, dark banners....

The archers were now upon the walls, taking up positions clearly meant to defend the castle from the invaders. Margaret rushed inside and down the steep, narrow stone staircase, slipping on the slick stone, but clutching the wall to prevent herself from falling.

William was in the hall, one hand on the hilt of his sword, his face pale. “We are under attack. There was a damned scout, Meg, watching us as we rode in! Were you on the ramparts? Did you see who is marching on us?”

Her heart was thundering. “I could not see their colors. But the banners are dark—very dark!”

They exchanged intense looks. The MacDonald colors were blue, black and a piping of red.

“Is it Clan Donald?” she cried.

“I would imagine so,” Will said harshly, two bright spots of color now on his cheeks.

“Will!” She seized his arm, and realized how badly she was shaking. “I hardly counted, but by God, I think there are hundreds of men approaching! They are so deep in rank and file, they could not fit upon the path we followed—they are coming up the glen below the ridge!”

He cursed terribly. “I am leaving my five best knights with you.”

It was so hard to think clearly now—as she had never been in a battle before, or in a castle about to be attacked. “What do you mean?”

“We will fight them off, Meg—we have no choice!”

She could not think at all now! “You cannot go to battle! You cannot fight off hundreds of men with our dozen knights and our few foot soldiers! And you cannot leave five knights with me! You would need every single one of them.”

“Since when do you know anything about battle?” he cried in frustration. “And our Comyn knights are worth ten times what any MacDonald brings.”

Oh, how she hoped he was right. Peg came racing into the chamber, her face so white it was ghostly. Margaret held out her hand and her lady’s maid rushed to her side, clasping her hand tightly. “It will be all right,” Margaret heard herself say.

Peg looked at her with wide, terrified eyes. “Everyone is saying it is Alexander MacDonald—the mighty Wolf of Lochaber.”

Margaret just looked at her, hoping she had misheard.

Sir Ranald rushed into the hall with Malcolm. “We will have to hurry, William, and try to entrap their army in the ravine. They cannot traverse the glen for much longer—they will have to take a smaller path that joins the one we came on. If we can get our men positioned above the ravine, there is a chance that we can pick them off, one by one and two by two—and they will not be able to get out of it alive.”

Was there hope, then? “Peg just said that it is the bastard brother.”

William became paler. Even Sir Ranald, the most courageous of their men, was still, his eyes wide and affixed to her.

One of Malcolm’s sons rushed inside, breaking the tension but confirming their fears. “It’s the Wolf,” he said grimly, eyes ablaze. “It’s Angus Mor’s bastard, the Wolf of Lochaber, and he has five or six hundred men.”

Margaret was deafened by her own thundering heartbeat. The Wolf of Lochaber was a legend in his own time. Everyone knew of Alexander MacDonald. It was said that no Highlander was as ruthless. It was said that he had never lost a battle. And it was said that he had never let his enemy live.

Dread consumed her. Margaret thought about the legend she had heard, gripping Peg’s hand more tightly.

Just a few years ago, Alexander had wished to marry his lover, the widowed daughter of Lord MacDuff, but he had been refused. So he had besieged the castle at Glen Carron in Lochaber. And when it finally surrendered, he had taken the laird prisoner, forced him to his knees, and made him watch as he coldly and ruthlessly executed those who had fought against him. He then burned Glen Carron to the ground. He had been about to hang Lord MacDuff, but his lover had begged for mercy. The Wolf had spared his future father-in-law’s life, but only after forcing him to swear fealty to him—and then he had kept him prisoner for several years. As for his lover, they were immediately married, but she died in childbirth a few months later.

If Alexander MacDonald was marching upon them, with hundreds of men, he would take Castle Fyne and he might destroy it before he was done.

“What should we do?” She did not know if she had ever been as afraid. But even as she spoke, a fierce comprehension began. Her question was foolish. They must defend the keep. Didn’t they have the combined force of about a hundred men with which to do so?

Sir Ranald was grim. “There are two choices, Lady Margaret. Surrender or fight.”

She inhaled. No Comyn and no MacDougall would consider surrender without a fight first.

“We will surprise him with an ambush at the ravine and stop him,” William said. He looked at Sir Ranald and Sir Neil, who had joined them, and Malcolm and his son. “Can such an ambush succeed?”

There was a hesitation—Sir Ranald exchanged glances with Sir Neil. “It is our only hope,” Sir Neil said.

Margaret felt her heart lurch with more dread. Peg seemed to moan at her side. Maybe the stories weren’t true, maybe God would help them—maybe, this one time, the Wolf would suffer defeat.

“We will ambush them at the ravine, then,” William said. “But Margaret—I want you to return to Bain, immediately.”

“You want me to flee?”

“You will do so with Sir Ranald and Sir Neil. If you leave now, you will be well out of any danger.”

Her mind was spinning—as if she was being whirled about while upside down. She could not leave! She glanced around at the women and children who had crowded into the hall. The menfolk, even the most elderly, were on the ramparts, preparing for battle.

Sir Ranald took her elbow. “He is right. You must be taken out of harm’s way. This castle belongs to you, which makes you a valuable bride—and a valuable prisoner.”

A chill swept over her. But she shrugged free. “I am not a coward—and I am not about to become anyone’s prisoner. I am lady of this keep! I can hardly flee like a coward, leaving you here, alone, to defend it. And what of the men, women and children here? Who welcomed me so warmly?”

“Damn it, Margaret, that is why you must go—because the castle is a part of your dowry. It makes you too damned valuable!” William shouted at her now.

She wanted to shout back. Somehow, she did not. “You go and you turn Alexander MacDonald back. In fact, do your best to make certain he never returns here! Ambush him in the ravine. Kill him, if you can!”

Peg gasped.

But Margaret’s mind was clear now. William would ride out with their men to fight the notorious Wolf of Lochaber. And if they could kill him, so be it. He was the enemy!

Sir Ranald turned. “Malcolm, send someone to the Earl of Argyll and another man to Red John Comyn.”

The Earl of Argyll—Alexander MacDougall—was her mother’s brother and he and Red John would surely come to their rescue. But both men were a day’s ride away, at least. And neither might be in residence; word might have to be sent farther afield.

Margaret stared as Malcolm rushed off, her mind racing. Sir Ranald said grimly to her, “If our ambush does not succeed, you will need help to defend the keep.”

It was hard to comprehend him now, and just as hard to breathe. “What are you saying?”

William spoke to Sir Ranald. “Should we prepare the ambush with the men we came with? And leave the castle garrison here?”

Margaret tried to think—why would they leave fifty men at the keep? And just as it dawned on her, Sir Ranald turned to face her. “You must prepare the castle for a siege.”

Her fear confirmed, she choked. She knew nothing of battles, and less of sieges. She was a woman—one of seventeen! “You will not fail!”

His smile was odd—almost sad, as if he expected the worst, not the best. “We do not intend to fail. And I hate leaving you, Lady Margaret, but we are undermanned—your brother needs me.”

She was shaking now. She prayed William and Sir Ranald would succeed in turning back Alexander MacDonald. “Of course you must go with William.”

William laid his hand on Sir Neil’s shoulder. “Stay with my sister and defend her, with your life, if need be.”

Sir Neil’s mouth hardened. Margaret knew he wanted to fight with William and Sir Ranald, but he nodded. “I will keep her safe and out of all harm,” he said harshly.

Margaret had the urge to weep. How could this be happening?

Malcolm rushed back into the hall. “I have sent Seoc Macleod and his brother. No one knows these forests the way they do.”

Suddenly Margaret thought about how bad the roads were—how thick with snow. Both men—Argyll and Red John—might be close, but reaching them would not be easy, not in the dead of winter.

“If we succeed in the ambush, we will not need Argyll or Red John,” Will said. He looked to Margaret. “If we fail, and he besieges this keep, it will be up to you to hold him off until our uncle or our cousin arrive.”

Their gazes had locked. She could only think of her utter lack of battle experience. William, who had been fighting the English since he was twelve, smiled at her. “Sir Neil will be at your side—and so will Malcolm.”

She managed to nod, fearfully. Then, wetting her lips, she said, “You will not fail, William. I have faith in you. God will see to our triumph. You will destroy MacDonald in the ravine.”

William suddenly kissed her cheek, turned and strode from the room, his huge sword swinging against his thigh. The other Buchan knights followed him, but Sir Ranald did not move, looking at her.

Margaret hugged herself. “Godspeed, Sir Ranald.”

“God keep you safe, Lady Margaret.” He hesitated, as if he wished to say more.

Margaret waited, but he only nodded at Sir Neil and Malcolm, then he ran after William and the others.

Margaret heard the heavy door slam closed and felt her knees buckle as they left. She was about to sink onto the closest bench, just for a moment, when she realized that every woman and child in the room was staring at her. The great hall was absolutely silent. Slowly, she turned around, scanning the faces of everyone present—noting each fearful and expectant expression.

She had to reassure them.

Yet what could she say, when she was so frightened? When their lives might well rest in her clumsy hands?

Margaret straightened her spine, squared her shoulders. She smiled, firmly. “My brother will succeed in driving the Wolf back,” she said. “But we will prepare for a siege. Start every fire. Bring up the casks of oil from the cellars. Begin boiling oil and water.” Peg stared at her, her mouth hanging open, and Margaret realized her tone had been oddly firm, so strangely commanding and decisive.

Margaret lifted her chin and added, “Bring up the stockpiles of rocks and stones. Prepare the catapults. And as soon as William has left, raise the drawbridge and lock it and set up the barricade.”

Murmurs of acquiescence greeted her. And as everyone left to do her bidding, Margaret prayed William would chase the Wolf of Lochaber away.

CHAPTER TWO

MARGARET STARED ACROSS the castle’s ramparts, feeling as if she had been transported to a different place and an earlier, frightening time. The battlements she had walked earlier no longer resembled any castle she had ever visited in her lifetime. Trembling, she hugged her mantle to her cold body.

The ramparts were crowded with casks of oil, piles of rock and stone, slings and catapults of various sizes, and a dozen pits for fires. All the women of the keep were present, as were a great deal of children—they had sorted through the rocks and stones, assembling the various piles by size and weight, while preparing the pits for the fires they might later light, some still coming and going with armloads of wood. Although the drawbridge was closed, a small side entrance in the north tower was being used now. Margaret had quickly realized that they could not run out of wood for the fires, or oil, or stones. Not if they were besieged.

Her archers remained at the walls. Perhaps fortunately—for so she was thinking—they only had two walls to defend. Because the keep was on the cliff overlooking the loch, two of its sides were insurmountable. They had three dozen archers on the vulnerable walls, and quivers of spare arrows were lined up behind each man. Another dozen warriors stood beside the archers, armed with swords, maces and daggers.

Margaret did not have to ask about the extra dozen soldiers. Although she had never been in a siege, she took one look at them and knew what their use might be: if the walls were successfully scaled, the archers would become useless. The battle for control of the castle would turn into hand-to-hand combat.

Margaret stared down at the glen, where the huge MacDonald army was gathered. It had not moved for the past three hours.

How she prayed that meant that William and Sir Ranald were picking off each and every enemy soldier as the Wolf attempted to traverse the ravine.

She felt a movement behind her and half turned. Malcolm smiled at her. If he was afraid, he had given no sign, but then, everyone seemed terribly brave. Margaret was so impressed with the courage of her people. She hoped that no one knew how her heart thudded, how light-headed she felt—how frightened and nervous she was.

“Has there been any word?” she whispered. Malcolm had sent two scouts out earlier to report on the ambush.

“Our watch has not returned,” he said. “But it is a good sign that the Wolf cannot move his men forward.”

She shivered. Hadn’t she also heard that the Wolf had a terrible temper? He would be furious at being thwarted. Unless, of course, he was dead.

How she prayed that was the case!

“Ye should go down, my lady,” Malcolm said kindly. “I ken ye wish to hearten the men and women, but it is growing very cold out, and if ye sicken, ye will dishearten them all.”

Margaret remarked Sir Neil, on the other side of the ramparts, as he and an elderly Highlander attempted to fix one of the catapults. Peg was with them, apparently telling them how she thought it best repaired. Had the situation not been so dire, Margaret would have been amused, for Peg was so nosy all of the time. And she was also a bit of a tease, and Sir Neil was terribly handsome with his fair complexion and dark hair.

He had been indefatigable. She did not know him well, but she was impressed with his tireless efforts on behalf of the keep—on her behalf.

Of course, if they were besieged and defeated, they would all die.

She looked at Malcolm. “Is it true?” She kept her voice low, so no one would overhear her. “That the Wolf slays all of his enemies—that he never allows the enemy to live?”

Malcolm hesitated, and she had her answer. “I dinna ken,” he said, with a shrug meant to convey ignorance.

How could such barbarism be possible? “Have you met him?”

Malcolm started. “Aye, my lady, I have.”

“Is he a monster, as claimed?”

Malcolm’s eyes widened. “Are such claims made? He is a powerful soldier—a man of great courage—and great ambition. ’Tis a shame he is our enemy and not our friend.”

“I hope he is dead.”

“He will not die in an ambush, he is far too clever,” Malcolm said flatly. And then his gaze veered past her and he paled.

Margaret whirled to stare down into the glen and she choked. The army was moving, a slow rippling forward, like a huge wave made of men. “What does that mean?” she cried.

Before Malcolm could answer, Sir Neil came running across the ramparts with a red-haired Highlander, Peg following them both. “Lady Margaret,” Sir Neil said. “One of our watch has returned and he wishes a word with you!”

Margaret took one look at the watchman’s frozen face and knew the news was not what she wished for it to be. And while she wanted to shout at him to declare the tidings, she held up her hand. “You are?”

“Coinneach MacDougall, my lady.”

“Please, step aside with me. Malcolm, Sir Neil, you may join us.” Her heart was thundering, aware that everyone upon the battlements was gazing at them. She led the three men down the narrow stairwell and into the great hall, where she turned to face them. “What happened?” She kept her tone quiet and calm.

“The ambush has failed, my lady. The Wolf and his army are passing through the ravine now. Within an hour, they will be at our front gates,” Coinneach said, his expression was one of dismay.

She knew she must not allow her knees to give way—not now. “Are you certain?”

“Yes. Some dozen of his knights are in the pass, even now.”

Margaret stared at him, unseeingly. “My brother? Sir Ranald?”

“I dinna ken, my lady.”

She supposed no news was better than the news of their deaths. Please God, she thought, let William and Sir Ranald be alive—please!

She did not think she could bear it if she lost her brother.

“Do you know if any of our men are alive?” she asked.

“I saw a handful of yer knights, my lady, fleeing into the forest.”

She breathed hard. “They will return here, if they can.” She had no doubt.

“It might be better if they rode hard and fast for Red John or Argyll,” Sir Neil said. “We will soon be under siege, and they could attack MacDonald from the rear.”

Maybe her men were not returning, after all. She squashed her instant dismay, turning back to Coinneach. “Is the Wolf—is Alexander MacDonald—alive?”

“Aye—he is at the very front of his men,” Coinneach said, his blue eyes now reflecting fear.

She felt sick.

Footsteps pounded down the stairwell, and they all turned toward the sound. Peg skidded into the hall, her eyes wide. “A man is below, outside the barbican—with a white flag!”

Margaret was confused. She turned to Malcolm, who said quickly, “The Wolf has sent a messenger ahead, my lady, I have little doubt.”

She felt her eyes widen. “What could he possibly want?”

“Yer surrender.”

* * *

MARGARET PACED FOR the next half an hour, as she waited for Sir Neil and Malcolm to disarm the messenger—verifying that was what he was—and then bring him safely and securely to her. Peg sat on one of the benches at one of the trestle tables, staring at her, her expression aghast. Margaret was accustomed to her friend’s wit and humor, not to her silence and abject fear.

She turned as they entered through the front door, having used the narrow side entrance in the north tower. A tall Highlander in the blue, black and red plaid walked inside, between Sir Neil and Malcolm. He was middle-aged, bearded and lean. He had been disarmed—his scabbard was empty, as was the sheath on his belt where a dagger should hang.

When he saw her he smiled, but not pleasantly. Margaret shivered.

“Margaret of Bain?” he asked.

She nodded. “Do you come from the Wolf?”

“Aye, I do. I am Padraig MacDonald. He wishes to parley, Lady Margaret, and I am instructed to tell you as much. If you agree, he will bring three men, and you may bring three men, as well. He will keep his army below the barbican, and you can meet just outside its walls.”

Margaret stared, incredulous. Then she glanced at Malcolm and Sir Neil. “Is this a trap?”

“Parleys are not uncommon,” Malcolm said. “But the Wolf is canny—he doesn’t keep his word.”

“It is a trap,” Sir Neil said firmly. “You cannot go!”

Margaret could not even swallow now. She faced the messenger. “Why does he wish to parley? What does he want?” As she spoke, Peg came to stand beside her, as if protectively.

“I was told to offer you a parley, lady, that is all. I dinna ken what he will speak of.”

Parleys might not be uncommon amongst warriors, but she was not a warrior, she was a woman—and her every instinct was to refuse.

“You cannot go,” Sir Neil said again, blue eyes flashing. “He will take you hostage, lady, faster than you can blink an eye!”

It was so hard to think! She stared at Sir Neil. Then she looked at the messenger, Padraig. “Please stand aside.”

Malcolm took him by the arm and moved him out of earshot. Margaret stepped closer to Sir Neil, with Peg. Breathing hard, she said, “Is there any way I could meet him and we could take him prisoner?”

From the look in Sir Neil’s eyes, Margaret knew he thought she had gone mad.

Peg said, “Margaret! He is the Wolf! Ye will never ambush him! He will take ye prisoner, and then what?”

“Dinna even think of turning the tables on him, lady,” Malcolm said, having returned.

Margaret glanced briefly at the messenger, who was staring—and almost smirking—at them. What did he know that they did not? “Is there any way we could parley without my being in danger of being taken captive?”

“It is too dangerous,” Sir Neil said swiftly. “I swore to Sir Ranald that I would keep you safe. I cannot let you meet the Wolf!”

“Margaret, please! I am but a woman, and even I know this is a trap!” Peg cried.

“Even if it is not a trap, too much can go wrong,” Malcolm said, sounding calm in comparison to the rest of them.

He was right. And Margaret was afraid to step outside the castle walls. Besides, she would never convince the damned Wolf to retreat. She squared her shoulders and left the group, walking over to the waiting Highlander. As she approached, his eyes narrowed.

Margaret smiled coldly at him. “Tell the great Wolf of Lochaber that Lady Comyn has refused. She will not parley.”

“He will be displeased.”

She refrained from shivering. “But I wish to know what he wants. Therefore, you may return to convey his message to me.”

“I dinna think he will wish for me to speak with ye again.”

What did that mean? Would the Wolf now attack? Her gaze had locked with Padraig’s. His was chilling.

A moment later, Sir Neil and Malcolm were escorting him out. The moment he was gone, Margaret collapsed upon the bench. Peg rushed to sit beside her, taking her hands. “Oh, what are we going to do?”

Margaret couldn’t speak. Was the Wolf now preparing to attack her? He certainly hadn’t come this far to turn around and go away! And what of William and Sir Ranald? If only they were all right! “Maybe I should have met him,” she heard herself say hoarsely.

“I would never let ye meet with him!” Peg cried, now close to tears. “He is an awful man, and all of Scotland knows it!”

“If you cry now, I will slap you silly,” Margaret almost shouted, meaning her every word.

Peg sat up abruptly. The tears that had seemed imminent did not fall.

“I need you, Peg,” Margaret added.

Peg stared and attempted to compose herself. “Can I bring ye wine?”

Margaret wasn’t thirsty, but she smiled. “Thank you.” The moment Peg had left, she stood up and inhaled.

Oh, God, what would happen next? Could she possibly defend the castle—at least until help arrived? And what if help did not arrive?

Surely, eventually, her maternal uncle, Alexander MacDougall of Argyll, would come. He despised every MacDonald on this earth. He would wish to defend the keep; he would want to battle with them.

Red John Comyn would also come to her aid if he knew what was happening. He was her uncle’s closest ally and his cousin. But time was of the essence. They had to receive word of her plight now. They had to assemble and move their armies now!

Her head ached terribly. There were so many decisions to make. The weight of such responsibility was crushing. And to think that in the past, she had never made a decision greater than what she wished to wear or what to serve for the supper meal!

Booted steps sounded, and with dread—she now recognized the urgency in Sir Neil’s stride—she turned as he stormed into the hall. “He is at the bridge, below your walls—and he wishes to speak with you.”

She froze. “Who?” But oh, she knew!

“MacDonald,” he said, eyes blazing.

Her stomach churned and her heart turned over hard. Only a quarter of an hour had passed since Padraig had left. If the Wolf of Lochaber was outside her gates, clearly he had been there all along.

And suddenly, like a small, frightened child, she felt like refusing the request. She wanted to go to her chamber and hide.

“I can take you up to the ramparts,” Sir Neil said bluntly.

It crossed her dazed mind that Sir Neil would only suggest such a course of action if it was safe, and of course, if the Wolf wished to parley now, she must go. She fought to breathe. It was safe for her to be high up on the ramparts, surrounded by her knights and archers, as they spoke. She felt herself nod at Sir Neil.

But as they started for the stairwell, comprehension seized her. She halted abruptly. How could it be safe for him to come to her castle walls?

He would be exposed to her archers and knights.

She looked at Sir Neil with sudden hope. “Can our archers strike him while we speak?”

Sir Neil started. “They are waving a flag of truce.”

What she had suggested was dishonorable, and she knew Sir Neil thought so. “But is it possible?”

“He will undoubtedly be carrying a shield, and he will be surrounded by his men. The shot would not be an easy one. Will you violate the truce?”

She wondered if she was dreaming. She was actually considering breaking a truce and murdering a man. But she knew she must not stoop to such a level.

She had been raised to be a noble woman—a woman of her word, a woman of honor, a woman gentle and kind, a woman who would always do her duty. She could not murder the Wolf during a truce.

Finding it difficult to breathe evenly, Margaret went up the narrow stairwell, Sir Neil behind her. As she stepped outside onto the ramparts, it was at once frigidly cold and uncannily silent. There was light, but no sun. Her archers remained, as did her dozen soldiers and the women and children who had been present earlier. But it almost seemed as if no one moved or breathed.

Sir Neil touched her elbow and she crossed the stone battlements, still feeling as if she were in the midst of a terrible dream, trying to find her composure and her wits before she spoke with her worst enemy. Standing just a hand-span from the edge of the crenellated wall, she looked down.

Several hundred men were assembled between the barbican and the forest. In the very front they stood on foot, holding shields, but behind them the soldiers were mounted on horseback. Above the first columns a white flag waved, and beside it, so did a huge black-and-navy-blue banner, a fiery red dragon in its center.

And then Margaret saw him.

The rest of the army vanished from her sight. Frozen, she saw only one man—the Highlander called the Wolf of Lochaber.

Alexander MacDonald was the tallest, biggest, darkest one of all, standing in the front row of his army, in its very center. And he was staring up at her.

Black hair touched his huge shoulders, blood stained his leine and swords, a shield was strapped to one brawny forearm, and he was smiling at her.

“Lady Comyn,” he called to her. “Yer as fair as is claimed.”

She trembled. He was exactly as one would have expected—taller than most, broader of shoulder, a mass of muscle from years spent wielding swords and axes, his hair as black as the devil’s. His smile was chilling, a mere curling of his mouth. She stared down at him, almost transfixed.

And when he did not speak again, when he only stared—and when she realized she was speechlessly staring back—she flushed and found her tongue. “I have no use for your flattery.”

The cool smile reappeared. “Are ye prepared to surrender to me?”

Her mind raced wildly—how could she navigate this subject? “You will never take this keep. My uncle is on his way, even as we speak. So is the great Lord Badenoch.”

“If ye mean yer uncle of Argyll, I canna wait. I look forward to taking off his head!” he exclaimed, with such relish, she knew he meant his every word. “And I dinna think the mighty Lord of Badenoch will come.”

What did that mean? She shuddered. “Where is my brother?”

“He is safely in my keeping, Lady Comyn, although he has suffered some wounds.”

She was so relieved she had to grip the wall to remain standing upright. “He is your prisoner?”

“Aye, he is my prisoner.”

“How badly is he hurt?”

“He will live.” He added, more softly, “I would never let such a valuable prisoner die.”

“I wish to see him,” she cried.

He shook his head. “Yer in no position to wish fer anything, Lady Comyn. I am here to negotiate yer surrender.”

She trembled. She wanted to know how badly William was hurt. She wanted to see him. And hadn’t Malcolm said that the Wolf was a liar? “I will not discuss surrender, not until you have proven to me that my brother is alive.”

“Ye dinna take my word?”

She clutched the edge of the wall. “No, I do not accept your word.”

“So ye think me a liar,” he said, softly, and it was a challenge.

Margaret felt Sir Neil step up behind her. “Show me my brother, prove to me he is alive,” she said.

“Ye tread dangerously,” he finally said. “I will show ye Will, after ye surrender.”

She breathed hard.

He slowly smiled. “I have six hundred men—ye have dozens. I am the greatest warrior in the land—yer a woman, a very young one. Yet I am offering ye terms.”

“I haven’t heard terms,” she managed to say.

That terrible smile returned. “Surrender now, and ye will be free to leave with an escort. Surrender now, and yer people will be as free to leave. Refuse, and ye will be attacked. In defeat, no one will be spared.”

Margaret managed not to cry out. How could she respond—when she did not plan to surrender?

If only she knew for certain that Argyll and Red John were on their way with their own huge armies! But even if they were, for how long could she withstand the Wolf’s attack? Could they manage until help arrived?

For if they did not, if he breached her walls, he meant to spare no one—and he had just said so.

“Delay,” Sir Neil whispered.

Instantly Margaret understood. “You are right,” she called down. “You are known as the greatest warrior in the land, and I am a woman of seventeen.” How wary and watchful he had become. “I cannot decide what to do. If I were your prisoner and my brother were here in my stead, he would not surrender, of that I am certain.”

“Are ye truly thinking to outwit me?” he demanded.

“I am only a woman. I would not be so foolish as to think I could outwit the mighty Wolf of Lochaber.”

“So now ye mock me?”

She trembled, wishing she hadn’t inflected upon the word mighty.

“Yer answer, Lady Margaret,” he warned.

She choked. “I need time! I will give you an answer in the morning!” By morning, maybe help would have arrived.

“Ye call me a liar and think me a fool? Lady Margaret, the land is at war. Robert Bruce has seized Dumfries Castle—and Red John Comyn is dead.”

She cried out, her world suddenly spinning. “Now you lie!” What he claimed was impossible!

“Yer great Lord of Badenoch died in the Greyfriars Church at Dumfries, four days ago.”

She turned in disbelief. Sir Neil looked as stunned as she was. Could the patriarch of their family be dead? If so, Red John was not coming to her aid! “What do you mean—Red John died? He was in good health!”

Slowly, the Wolf smiled. “So ye want the facts? Ye’ll hear soon enough. He was murdered, Lady Comyn, by Bruce, although he did not deliver the final, fatal blows.”

Margaret’s shock knew no bounds. Had Robert Bruce murdered Red John Comyn?

If so, the land would most definitely be at war!

“Bruce is on the march, Lady Comyn, and yer uncle, the MacDougall, is on the march, as well—in Galloway.” He stared coldly up at her. “And do ye not wish to know where yer beloved Sir Guy is?”

Sir Neil had taken her arm, as if to hold her upright.

“He was also at Dumfries, sent there to defend the king.”

She had not given her betrothed a thought since that morning. Had Sir Guy fought Bruce at Dumfries? If so, he was but two days away. She did not know what the Highlander was implying, but Sir Guy would surely come to her rescue. “This castle is a part of my dowry. Sir Guy will not let it fall.”

“Sir Guy fights Bruce, still. Argyll is in battle in Galloway. The Lord of Badenoch is dead. Ye have no hope.”

Now she truly needed time to think—and attempt to discover if his claims were true. For if they were, she was alone, and Castle Fyne would fall.

“He could be lying,” Sir Neil said, but there was doubt in his tone.

She met his gaze and realized he was frightened after all. But then, so was she. She turned back to the Highlander standing below her walls. “I need a few hours in which to decide,” she said hoarsely.

“Yer time is done. I demand an answer, lady.”

She began shaking her head. “I don’t want to defy you.”

“Then accept my generous terms and surrender.”

She bit her lip and tasted her own blood. And she felt hundreds of pairs of eyes upon her—every man in his army stared at her—as did every man, woman and child upon the ramparts. She thought she heard Peg whisper her name. And she knew that Sir Neil wanted to speak to her. But she stared unwaveringly at the Wolf of Lochaber. As she did, she thought of her mother—the most courageous woman she had ever known. “I cannot surrender Castle Fyne.”

He stared up at her, a terrible silence falling.

No one moved now—not on the ramparts, not in his army.

Only Margaret moved, her chest rising and falling unnaturally, tension making it impossible to breathe normally.

And then a hawk wheeled over their heads, soaring up high into the winter sky, breaking the moment. And disgust covered the Wolf’s face. Behind him, there were murmurs, men shifting. More whispers sounded behind her. The sounds were hushed, even awed, from behind and below.

Finally, he spoke, coldly. “Yer a fool.”

She did not think she had the strength to respond. Sir Neil flinched, his hand moving to his sword. She had to touch him, warning him not to attempt to defend her. She then faced the dark Highlander below her again. “This castle is mine. I will not—I cannot—surrender it.”

She thought that his eyes now blazed. “Even if ye fight alone?”

“Someone will come.”

“No one will come. If Argyll comes, it will be after the castle has fallen.”

She swallowed, terrified that he was right.

It was a moment before he spoke again, and anger roughened his tone. “Lady Margaret, I admire yer courage—but I dinna admire defiance, not even in a beautiful woman.”

Margaret simply stared. She had given him her answer, there was nothing more to say.

And he knew it. The light in his eyes was frightening, even from this distance. “I take no pleasure in what I must do.” He then lifted his hand, but he never removed his eyes from her. “Prepare the rams. Prepare the siege engines. Prepare the catapults. We will besiege the castle at dawn.” And he turned and disappeared amongst his men, into his army.

Margaret collapsed in Sir Neil’s arms.

* * *

PEG SHOVED A cup of wine at her. Margaret took it, desperately needing sustenance. They were seated at one of the trestle tables, in the great hall. Night was falling quickly.

And at dawn, the siege would begin.

Sir Neil sat down beside her, not even asking permission. Malcolm took the opposite bench. Peg cried, “Ye should have surrendered, and it isn’t too late to do so!”

Margaret tensed, aware that Peg was terrified. When she had left the ramparts, she had gazed at some of the soldiers and women there—everyone was frightened. And how could they not be?

Alexander MacDonald had been forthright. If they did not surrender, he would defeat the castle and spare no one.

She hugged herself, chilled to the bone. Should she have surrendered? And dear God, why was such a decision hers to make?

She inhaled and set the cup down. “Is it possible he is telling the truth? Is it possible that Red John is dead—and that Robert Bruce has seized the royal castle at Dumfries?”

Sir Neil was pale and stricken. “Bruce has always claimed the throne, but I know nothing of this plot!”

“Even the Wolf would not make up such a wild tale,” Malcolm said. “I believe him.”

She could barely comprehend what might be happening. “Is Bruce seeking the throne of Scotland? Is that why he attacked Dumfries?” And did that mean that Sir Guy was there with his men? Sir Guy was in service to King Edward. He was often dispatched to do battle for the king. Was that why MacDonald had claimed no one would come—because Sir Guy would be occupied with his own battles for King Edward?

Sir Neil shook his head. “Bruce is a man of ambition, but to murder Red John? On holy ground?”

“If the damned Wolf is telling us the truth,” she said, “if Red John has been murdered, Buchan will be furious.” The Comyns and Bruces had been rivals for years. They had fought over the crown before—and the Comyns had won the last battle, when their kin, John Balliol, had become Scotland’s king. “A great war will ensue.” She was sickened in every fiber of her being—these events were too much to bear.

“Lady Margaret—what matters is that if this is true, Red John will not be coming to our aid. Nor will Sir Guy.”

Margaret stared at Malcolm as Peg cried, “We can still surrender!”

She ignored her maid. “But Argyll will come to our aid if he can.”

“If the land is at war, he might not be able to come,” Sir Neil said grimly. “And MacDonald claims he has the means to stop him.”

She looked at Sir Neil and then Malcolm. “I am frightened. I am unsure. So tell me, truly, what you think I should do?”

Malcolm said, “Your mother would die defending Castle Fyne.”

Sir Neil stood. “And I would die to defend you, my lady.”

God, these were not reassuring answers!

“But, my lady, if you decide you wish to surrender, I will support you,” Malcolm said.

Sir Neil nodded in agreement. “As would I. And no matter what MacDonald has said, you can decide to surrender at any time—and sue him for the terms he has already said he would give you.”

But that did not mean the Wolf would give her such terms. He had been very angry when they had last parted company.

Margaret closed her eyes, trying to shut out the fear gnawing at her. She tried to imagine summoning MacDonald and handing him the great key to the keep. And the moment she did so, she knew she could not do such a thing, and she opened her eyes. They all stared at her.

“We must fight, and pray that Argyll comes to our aid,” Margaret said, standing. If they were going to fight, she must appear strong, no matter how terrified.

The men nodded grimly while Peg started to cry.

* * *

MARGARET DID NOT sleep all night, knowing what would begin at dawn. And because Peg kept telling her that she must surrender, and that she was a madwoman to think to fight the Wolf of Lochaber, she had finally banned the maid from her chamber. Now, she stood at her chamber’s single window, the shutters wide. The black sky was turning blue-gray. Smoke filled the coming dawn. The sounds of the soldiers and women above her on the ramparts, speaking in hushed tones as they stoked the fires and burned pots of oil, drifted down to her.

She could not bear the waiting, and she had never been as apprehensive. She heard footsteps in the hall on the landing, and she picked up her mantle, threw it on and hurried out. Sir Neil stood there, holding a torch.

“Are we ready?” she asked.

“As ready as we can be. If they think to scale our walls, they will be badly burned, at the least.”

And that was when she heard a terrible sound—a huge and crushing sound—accompanied by the deep groaning of wood.

“It has begun,” Sir Neil said. “They are battering the first gates on the barbican.”

“Will they break?”

“Eventually,” he said.

Margaret hurried past him, heading for the stairwell that went up to the crenellations. He seized her arm from behind. “You do not need to go up!” he exclaimed.

“Of course I do!” She shook him off and raced upstairs, stepping out into the gray dawn.

Smoke filled the air from the dozen fire pits, as did the stench of burning oil. The sky was rapidly lightening, and Margaret saw men and women at the walls, but no one was moving. “What’s happening?” she asked.

Malcolm stepped forward and said, “They are just moving their ladders to our walls.”

Margaret had to see for herself, and she walked past him.

She stared grimly down. Dozens of men were removing ladders from carts drawn by horses and oxen, pushing them toward her walls. She could not tell what the hundreds of men behind them were doing, and she glanced south, toward the barbican. Several dozen men were pushing a huge battering ram forward. She held her breath as the wheeled wooden machine moved closer and closer to the gates, finally ramming into it.

The crash sounded. Wood groaned.

In dismay, she realized the gates of the barbican would not hold for very long. A slew of arrows flew from her archers upon the entry tower, toward those men attacking her barbican. Two of the Wolf’s soldiers dropped abruptly from their places by the battering ram.

Instantly, other soldiers ran forward, some to drag the injured away, others to replace them.

“It isn’t safe for you to remain up here,” Sir Neil said, and the words weren’t even out of his mouth before she saw more arrows flying—some toward the men below, who were erecting the ladders upon her walls, and others coming up toward her archers and the women on her ramparts. Sir Neil pulled her down to her knees, arrows flying over them and landing on the stone at their backs.

“You are the mistress of this castle,” Sir Neil said, their faces inches apart. “You cannot be up here. If you are hurt, or God forbid, if you die, there will be no one to lead us in this battle.”

“If I am hurt, if I die, you must lead them.” Just then, the arrows had not hit their targets, but she was not a fool. When the Wolf’s archers were better positioned, they would strike some of her soldiers, and perhaps some of the women now preparing to throw oil on the invaders. And as she thought that, she heard a strange and frightening whistling sound approaching them.

Instinctively, Margaret covered her head and Sir Neil covered her body with his. A missile landed near the tower they had come from, exploding into fire as it did. More whistles sounded, screaming by them, rocks raining down upon the ramparts now, some wrapped in explosives, others bare. Two men rushed to douse the flames.

Margaret got onto her hands and knees, meeting Sir Neil’s vivid blue gaze. “You must tell me what is happening—when you can.”

* * *