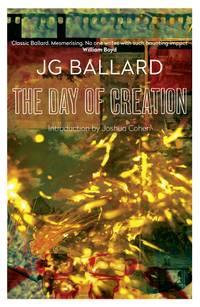

Читать онлайн книгу «The Day of Creation» автора J. Ballard

The Day of Creation

J. G. Ballard

‘Classic Ballard. Mesmerising. No one writes with such haunting impact’ William BoydIn parched, war-torn central Africa, Dr Mallory watches his clinic fail and dreams of discovering a third Nile to make the Sahara bloom. During his search for water, an ancient tree stump is uprooted by a bulldozer and water wells up, spreading until it becomes an enormous river. With the once arid land now abounding in birds and beasts, the obsessed Mallory forges up-river in an old car ferry, clashing with hostile factions as he tries to find the source of his own creation.

J. G. BALLARD

The Day of Creation

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road London W6 8JB 4thestate.co.uk (http://4thestate.co.uk)

This edition published by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in Great Britain by Victor Gollancz 1987

Copyright © J. G. Ballard 1987

The right of J. G. Ballard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

Introduction copyright © Joshua Cohen 2014

Interview copyright © Travis Elborough 2006

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins eBooks.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this e-book has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Cover by Stanley Donwood.

Overlaid image partly derived from combustion of ammonium dichromate, carried out by Dr Roy Lowry at Plymouth University; photographed by Anna Walker.

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2010 ISBN: 9780007290116

Version: 2014-09-25

Praise (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

From the reviews of The Day of Creation:

‘It could only have been imagined by a master of visionary realism…a country of the mind as vivid and viable as anything this extraordinary writer has ever produced’

Spectator

‘Ballard continues to prove that his imagination is unmatched by any contemporary British writer. His vision is relentless. Ballard’s acrid landscapes of a surreal and glittering Africa disturb as well as entrance. The obsessive desires of the hero, Dr Mallory, are equalled only by the compulsion Ballard’s creative genius has to write’

Glasgow Herald

‘Part spellbinding story, part fable for our time, Ballard’s novel is a vividly cinematic but nightmarish vision of a corrupted world. In a narrative filled with ironies, Ballard’s prose is honed and supple, often flowering into vivid lyricism. A mesmerizing tale by a master of the craft, one that resonates with dark implications for the future of humanity on this planet’

Publishers Weekly

Contents

Title Page (#u3e5055e0-9c6a-56b2-a028-192fe6a2310f)

Copyright (#ud7a6d98d-e22b-508e-96ce-5f3bbdaa1352)

Praise

Introduction by Joshua Cohen

1 The Desert Woman

2 The Gunmen

3 The Third Nile

4 The Shooting Party

5 Fame

6 The Oak and the Spring

7 The Impresario of Rubbish

8 The Creation Garden

9 The River Mallory

10 The Cascade

11 The House of Women

12 Noon

13 Piracy

14 Out of the Night and into the Dream

15 The Naming of New Things

16 The Helicopter Attack

17 Escape

18 The Green World

19 The Lanterns at Dusk

20 The Documentary Film

21 The Skirmish

22 Into the Lagoons

23 Journey Towards the Rain Planet

24 A Dream of Fair Women

25 The Wildfowlers

26 The Gardens of the Sahara

27 The Stolen Channel

28 Doctor Mal

29 The Blue Beaches

30 The Arcade Peep-Show

31 The Death of the Diana

32 The Poisoned Valley

33 The River Search

34 The Source

35 Memory and Desire

Interview with J. G. Ballard

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Introduction (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

by Joshua Cohen

1

‘Dreams of rivers, like scenes from a forgotten film, drift through the night, in passage between memory and desire.’

Or, better, let’s set it like a poem:

Dreams of rivers,

like scenes from a forgotten film,

drift through the night,

in passage between memory and desire.

Now it reads less like a first sentence – which it is, the first sentence of J. G. Ballard’s The Day of Creation – and more like the novel’s displaced epigraph.

Now we can begin, and I’ll gush about this and leak about that and then this introduction will trickle to an end and you’ll begin the novel proper only to find that sentence again and perhaps you’ll feel – perhaps you’ll feel now that I’m exhorting you to – the prosodic ebbs and flows of water. The opening sentence of Finnegans Wake is the continuation, the circumfluence, of its closing sentence. Joyce’s first page begins: ‘riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.’ His last page ends: ‘A way a lone a last a loved a long the’

No capitalization at top, no punctuation at bottom.

Of course, Joyce also wrote poetry and his prose was ‘poetic’ – whereas we read Ballard for a pitilessly mass-produced language more suitable to ‘the contemporary’. Or we assume we do (or we assume pitiless mass-production is more suitable), because the stark sad thingness of drainage culverts and overpasses and parking lots and empty swimming pools – empty except for the junkfood wrappers and condoms and cigpacks and bottles – too often overwhelms the ambient mosquito music abounding.

Prose lets us see and poetry lets us hear but the best of both do both at once, though so does 3D IMAX with Dolby Digital.

So, ‘like scenes from a forgotten film’ – what does Ballard mean? Who forgot this film and why? Rather, is this line disposable? Or is a brackish meaning bubbling behind it? In film, by which I mean mostly in Hollywood, when everything’s been shot and edited and even reshot and re-edited and test audiences still can’t understand what the hell’s going on, directors or, frequently, producers in conflicts with their directors, seek to salvage the thing either by introducing voice-over – from the hero, perhaps, or an omniscient God-narrator, explaining, ‘An hour before dawn, while I slept in the trailer beside the drained lake, I was woken by the sounds of an immense waterway’ – or by slapping together a title card that proclaims: ‘Africa, The Present.’

‘Like scenes from a forgotten film’ strikes me as Ballard’s equivalent of this technique. The line introduces a first-person narrator (first-person is literature’s overdubbing), while it also serves to reorient – or deoccident – you, the reader, for whom film, or TV – the screen – has become so primary a medium as to be beyond second nature: The mediation has become Nature Itself.

After that line Chapter 1 continues its cinematic panning:

As on all weekend visits to the abandoned town, I was seized by the vision of a third Nile whose warm tributaries covered the entire Sahara. Drawn by my mind, it flowed south across the borders of Chad and the Sudan, running its contraband waters through the dry river-bed beside the disused airfield.

But everything’s so vivid that you’d be forgiven for not having noticed that the theatre you’re in is still just a skull: one man ‘seized by the vision’, a Nile ‘drawn by my mind’. It’s as if we have to be ensconced in an imitative darkness before that line about film is granted its literal justification, in the midst of the chapter: refugees from the Sudan are feeding campfires with wood stripped from a police boat, using ‘strips of celluloid left behind by the film company’ as accelerant.

2

In 1984 Ballard published his first and only overtly autobiographical novel, which was also his first and only mainstream success, Empire of the Sun. In 1987, the film version appeared, and Ballard’s next novel was published – The Day of Creation, whose somniloquent symbolism alienated whatever new audience Empire had earned, and failed to interest the old audience already alienated by the Hollywoodization – the Spielberging – of a cult author and genre-totem (who was also a 57-year-old single father of three). The Day of Creation has never been filmed, though it’s already a series of action scenes strewn with dialogue sparse enough for the markets abroad. What augurs against adaptation, however, is that it has no elevator-pitch – no plot.

The hero of The Day of Creation is Dr Mallory, a Brit born in Kowloon, Hong Kong (Ballard was born in Shanghai), trained in Ireland as a physician (Ballard trained at Cambridge to be a physician), who now administers a clinic for the World Health Organization in Port-la-Nouvelle, the second city/shantytown of an unnamed, formerly French colonial ‘war-locked nation, that lay between the borders of Chad, the Sudan, and the Central African Republic in the dead heart of the African continent’. That war pits General Harare’s guerilla units against a paramilitary police force commanded by Captain Kagwa. Repeated clashes have wrecked Port-la-Nouvelle’s viaducts and reservoir, left the local Lake Kotto dry, and sent the engineers involved with irrigation drilling fleeing back to Belgium. Mallory is captured and about to be executed by Noon, a prepubescent girl and Harare rebel, but her rifle jams, and her co-revolutionaries scatter to the forest with the arrival of Kagwa’s squadrons and the landing of a twin-engine Dakota chartered to Air Centrafrique. Mallory’s life is saved, or his death is, with a popcorny fortuity. If the rifle had functioned properly the rest of the novel would’ve been the soul’s passage through delirium, and all its waterways would be the Styx.

The Dakota’s passengers are Professor Sanger, an Australian-German ‘sometime biologist turned television popularizer’, and his Indian protégé Mr Pal, who’ve come to deliver five tons of rice donated by West Germany – to a populace that has never eaten rice, to an uninhabited town – and to make a self-financed documentary – about the war, about Kagwa, about anything – for Africa Green, a ‘television charity’, which maintains ‘satellite links with the major Japanese networks’.

Sanger settles for producing agitprop by and about and even for Kagwa – a viewership of one. Mallory, meanwhile, maniacally schemes to reverse the drought. Literature teems with mad mariners – Mallory is its foremost mad hydrologist. He suspects, or prophesies, an underground limestone aquifer, and in the course of his divination campaign orders one of Kagwa’s sergeants to remove the stump of an ancient fallen oak. The tractor extracts the gnarled root-bole – ‘like the petrified heart of an extinct bull, or the crown of an underworld deity ripped from the ceiling of a subterranean palace’ – and exposes ‘an open mouth wide enough to swallow a small car’. But then water fills the cavity, black water, which gradually overflows it, and floods Lake Kotto, and washes the earth blank of its town: boats become the only tenable dwellings, as the Sahara engreens into ‘an Eden’.

Mallory purchases the river from Kagwa for $1000 US. Sanger senses an opportune subject for his documentary, and shoves his camera and mic in the doctor’s face, but only after he registers the river with the National Geographic Society in Washington, DC, naming it the Mallory. Noon, whether out of penance for her execution attempt, or in gratitude for the H

0, assists Mallory in commandeering a car-ferry, the Salammbo, and the two depart toward the river’s source, their objective changing like a stream of consciousness, or becoming a stream of consciousness: One moment Mallory wants to dam the Mallory, the next he wants to destroy it.

All of the above happens in a hundred or so pages. The nearly two hundred pages remaining are pure journey: Kagwa’s pursuit (to reclaim the car-ferry, which contains the Mercedes he bought with the river funds); Harare’s skirmishing; Sanger and Pal coming aboard to collect their leagues of unscripted footage, and the overtaking of the Diana: a ‘brothel-ship’, formerly patronized by oil-riggers, and now under the commission of Mrs Warrender, another Brit, another white, who’d superintended the animal breeding station with her Rhodesian husband, until he was slaughtered …

3

Think back, now, to the way movies used to be – not on computers, but in halls – not digital, but analogue, a succession of frames flowing off a reel like water until all that was left was a flume of hot white light projecting its pristination at a screen. Think back to the size of the screens and so to the size of the people on them – people firmamental, stars – skygods enacting myths in perpetual sequel.

What I mean is: Apocalypse Now. Directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1976 but released only in 1979. Apocalypse Now features title cards and is narrated by Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), who is dispatched upriver – the fictional Nung River – to terminate Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who has ‘gone native’, and formed a private militia to fight his private wars. The film’s production was notoriously plagued: principal photography in the Philippines was interrupted by typhoon season; Harvey Keitel was fired (for reasons never publicized), and replaced by Sheen, who promptly had a heart attack; Brando showed up unprepared, obese, and with his head shaved; Dennis Hopper, who plays a traumatized photojournalist, was method acting his way through a coke-binge. At least ‘the extras’ were reliable – scores of Vietnamese who’d fled one violent insurrection for another. President Marcos regularly demanded the return of the army helicopters the production were renting, which he scrambled to surveil and even strafe the New People’s Army of the illegal CPP, the Communist Party of the Philippines. This drama behind the drama made its way into a documentary assembled by Eleanor Coppola, in which her director-husband can’t stop himself from airing the resemblance between the psychologies of artistic creation and military-industrial destruction: ‘We were in the jungle, there were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane.’

Hearts of Darkness is the title of that making-of documentary, and it’s obvious to everyone sweating in it – except Brando, who refused to do any reading – that Apocalypse Now is based on Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In that novella, Marlow, the original of Willard, steamboats up the Congo River scouring the rainforest for the rogue ivory-trader, and slaver, Kurtz. In Conrad’s telling neither Marlow nor Kurtz are elite soldiers, but are or were employees of ‘the Company’, and the setting is the Central African Congo Free State, which was, in fact, a corporation wholly owned and operated by Belgium. Another liberty Coppola took: his Kurtz is assassinated by Willard, while the page-bound Kurtz dies slowly, and Marlow falls ill, from ‘an impalpable greyness’, ‘a sickly atmosphere of tepid scepticism’. Heart of Darkness was serialized in 1899, and republished in 1902 as the middle novella of a trilogy that bridged the stages of terraqueous life: preceding it is Youth, in which the foreign is exotic, yet nurturing; following it is The End of the Tether, in which the foreign has become indistinguishable from home and the only Empire left is a watery grave. Between the two fictions – between birth and death – is dream: ‘It seems to me I am trying to tell you a dream – ’ Marlow says, ‘making a vain attempt, because no relation of a dream can convey the dream-sensation, that commingling of absurdity, surprise, and bewilderment in a tremor of struggling revolt, that notion of being captured by the incredible which is of the very essence of dreams … ’

Heart of Darkness, of course, has its own ur-versions, its own unconscious – in the legends that European and Anglo-American writers translated from, and were inspired to invent by, the African and Asian cultures they nonetheless regarded as ‘primitive’, or ‘inferior’. Stay close, because we’re approaching the Inmost Station.

We have stories about treasure hunters who leave their lands and wander the globe, only to be recalled by a dream of a willow in their house’s yard, under which a hoard of gems is buried; we have tales of hunters slaying wild boars whose carcasses metamorphose into the corpses of fathers. Then there’s ‘My First Day in the Orient’, an essay of around 1890 by the half-Greek, half-Irish Lafcadio Hearn, who spent two decades as a reporter and English tutor in Japan:

Then I reach the altar, gropingly, unable yet to distinguish forms clearly. But the priest, sliding back screen after screen, pours in light upon the gilded brasses and the inscriptions; and I look for the image of the Deity or presiding Spirit between the altar-groups of convoluted candelabra. And I see – only a mirror, a round, pale disk of polished metal, and my own face therein …

An adventurer seeks the divine, and finds himself instead. Tug aside the curtain, and the man is the Maker, and the Maker is the man – ‘The horror! The horror!’

Imagine if Apocalypse Now was filmed again with state-of-the-art CGI, so that Willard survives his river cruise only to discover that he is Kurtz. (Which would’ve been preferable, if Sheen had played both the roles? Or Brando?)

Imagine Heart of Darkness rewritten so that Marlow makes the same discovery – and now he is foundered, crazed, suicidal.

All this brings us, by a commodius vicus of recirculation, back to The Day of Creation, in which Mallory (which is ‘Marlow’ mixed with ‘Ballard’) sets out toward the source of his river, which might not be Lake Chad or the mountains of the Massif, but his own deluged deluded brain: malnourished, fevered. The River Mallory is the doctor’s crosscurrent double, an inconstant, alternately reflecting/reflected ‘black mirror’. ‘I tried to stand back from my own obsession,’ Mallory says, ‘but I could no longer separate myself from my dream of the Mallory.’

In the first book of the first of the books, the Bible, ‘The Day of Creation’ occurred a full week before Paradise even existed: ‘And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep,’ and everything would’ve been perfectly peaceful, if God hadn’t said, ‘Let there be light’ – and there was light. Ballard’s novel reminds us that we’ve suffered ever since for our projections.

Brooklyn, March 2014

1. Around 1969, George Lucas tried to make a version of the John Milius script, but his proposal to shoot it in 16mm as a pseudo-documentary on location in South Vietnam, with the war still in progress, found no support at the studios. Coppola channeled this conceit through a brief cameo in his own movie as a telejournalist yelling at Air-Cav soldiers who’ve just razed a village: ‘Don’t look at the camera! Just go by like you’re fighting!’ In 1971, Dennis Hopper released The Last Movie, which he directed and starred in as ‘Kansas’, a stuntman on a Western being filmed in Peru. Kansas stays on after the production has wrapped, and makes an attempt at a calmer if romanticized life with a native prostitute. Their idyll is threatened, however, once an indigenous tribe, misunderstanding the Hollywood fakery, fashions equipment out of bamboo and starts ‘filming’ a Western in which the violence isn’t staged, but fatal.

1 (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

The Desert Woman (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

Dreams of rivers, like scenes from a forgotten film, drift through the night, in passage between memory and desire. An hour before dawn, while I slept in the trailer beside the drained lake, I was woken by the sounds of an immense waterway. Only a few feet from me, it seemed to flow over the darkness, drumming at the plywood panels and unsettling the bones in my head. I lay on the broken mattress, trying to steady myself against the promises and threats of this invisible channel. As on all my weekend visits to the abandoned town, I was seized by the vision of a third Nile whose warm tributaries covered the entire Sahara. Drawn by my mind, it flowed south across the borders of Chad and the Sudan, running its contraband waters through the dry river-bed beside the disused airfield.

Had a secret aircraft landed in the darkness? When I stepped from the trailer I found that the river had gone, vanishing like a darkened liner between the police barracks and the burnt-out hulk of the cigarette factory. A cool wind had risen, and a tide of sand flowed over the bed of the lake. The fine crystals beside the trailer stung my bare feet like needles of ice, as the invisible river froze itself when I approached.

In the darkness the ivory dust played against the beach in a ghostly surf. Nomads had built small fires, refugees from the Sudan who rested here on their way south to the green forest valleys of the River Kotto. Each weekend I found that they had torn more planks from the hull of Captain Kagwa’s police launch, lighting the powdery timbers with strips of celluloid left behind by the film company. Dozens of these pearl-like squares emerged from the sand, as if the drained lake-bed was giving up its dreams to the night.

Once again I noticed that a strange woman had been here, gathering the film strips before they could be destroyed. I have seen traces of her for the past weeks, the curious footprints on the dispensary floor, with their scarred right heels and narrow thumb-like toes, and her absentminded housework around the trailer. For some time now I have suspected that she is keeping watch on me. Any food or cigarettes that I leave behind are always removed. I have even placed a small present for her on the trailer steps, a plastic viewfinder and a set of tourist slides of the Nile at Aswan, the humour of which might appeal to her. Last weekend, when I arrived at the trailer, I found that the mattress had been repaired with wire and string, though perhaps for her comfort rather than mine.

The thought that I may be sharing a bed with one of these young desert women adds a special glamour to my dreams of the night-river. If she suffers from eczema or impetigo I will soon carry the infection on my skin, but as I lie in the bunk I prefer to think of her naked to the waist, bathing in the warm waters that flow inside my head.

However, her main interest is clearly in the film strips. When I returned to the trailer I found a plastic bucket tucked behind the wooden step. I knelt in the cold dust, and searched through the curious rubbish which this young woman had collected – empty vaccination syringes from the dispensary floor, the sailing times of the Lake Kotto car ferry, a brass cartridge case and the lens cover of a cine-camera lay among the clouding film strips gathered from the beach.

Together these objects formed a record of my life, an inventory that summed up all the adventures that had begun in this shabby town in the northern province of a remote central African republic. I held the cartridge case to my lips, and tasted the strange scent, as potent as the memory of Noon’s embrace, that clung to its dull metal. I thought of my journey up the Mallory, and of my struggle with the great river which I had created and tried to kill. I remembered my obsession with Noon, my duel with Captain Kagwa’s helicopter, and all the other events which began a year ago when General Harare and his guerillas first came to this crumbling town.

2 (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

The Gunmen (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

‘Dr Mallory, are you going to be executed?’

I searched for the woman shouting to me, but a rifle barrel struck me across the shoulders. I fell to the ground at the gunmen’s feet, and cut my hand on a discarded canister of newsreel film which the Japanese photographer was feeding into her camera. In a few seconds, I realized, the expensive celluloid would see its first daylight while recording my own death.

Fifteen minutes later, when General Harare had withdrawn his guerillas into the forest, leaving the lakeside town he had occupied for a few frightening hours, I was still trying not to answer this all too loaded question. Thrown at me like a query at a chaotic press conference, it summed up the dangers of that last absurd afternoon at Port-la-Nouvelle.

Was I going to be shot? As the guerillas bundled me on to the beach below the police barracks, I called to the young Japanese in her silver flying overalls.

‘No! Tell Harare I’ve ordered a new dental amalgam for his men. This time the fillings will stay in …’

‘The fillings …?’

Hidden behind her hand-held camera, Miss Matsuoka was swept along by the group of excited soldiers running down to the lake, part beach-party and part lynch mob. There was a confusion of yodelling whoops, weapons playfully aimed at the sun, and knees twisting to the music that pumped from the looted radios and cassette players strung around the gunmen’s necks among their grenades and ammunition pouches.

There was a bellow from General Harare’s sergeant, a former taxi driver who must once have glimpsed a documentary on Sandhurst or St Cyr in a window of the capital’s department store. With good-humoured smiles, the soldiers fractionally lowered the volume of their radios. Harare raised his long arms at his sides, separating himself from his followers. The presence of this Japanese photographer, endlessly scurrying at his heels, flattered his vanity. He stepped from the beach on to the chalky surface of the drained lake-bed, stirring the milled fish bones into white clouds, a Messiah come to claim his kingdom of dust. Dimmed by heavy sunglasses, his sensitive, malarial face was as pointed as an arrowhead. He gazed piercingly at the horizons before him but I knew that he was thinking only of his abscessed teeth.

Behind me a panting twelve-year-old girl in an overlarge camouflage jacket forced me to kneel among the debris of beer bottles, cigarette packs and French pornographic magazines that formed the tide-line of the beach. Prodding me with her antique Lee-Enfield rifle, this child auxiliary had driven me all the way from my cell in the police barracks like a drover steering a large and ill-trained pig. I had treated her infected foot when she wandered into the field clinic that morning with a party of women soldiers, but I knew that at the smallest signal from Harare she would kill me without a thought.

Filmed by the Japanese photographer, the General was walking in his thoughtful tread towards the wooden towers of the artesian wells whose construction I had supervised for the past three months, and which symbolized the one element he most detested. I sucked at the wound on my hand, but I was too frightened to wet my lips. Praying that the wells were as dry as my mouth, I looked back at the deserted town, at the looted stores visible above the teak pillars of the jetty where the car ferry had once moored ten feet above my head. Behind the party of guerillas, some lying back on the beach beside me, others dancing to the music of cassette players, I could see a column of smoke lifting from the warehouse of the cigarette factory, like a parody of a television commercial for the relaxing weed. A pleasant scent bathed the beach, the aroma of the rosemary-flavoured tobacco leaf which the economists at the Institut Agronomique had decided would transform the economy of these neglected people, and provide a stable population from which the local police chief, Captain Kagwa, could recruit his militia.

Turned by the light wind, the smoke drifted towards the dusty jungle that surrounded the town, merging into the haze fed by an untended backyard incinerator. Beyond the scattered tamarinds and shaggy palms the whitening canopy of forest oaks stood at the mouth of a drained stream whose waters had filled Lake Kotto only two years earlier. Their dying leaves blanched by the sun, the huge trees slumped among the stony sand-bars, tilting memorials in a valley of bones.

I inhaled the scented air. If I was to be executed, it seemed only just that I, renegade physician in charge of the drilling mission whose water would irrigate the tobacco projects of Port-la-Nouvelle and supply the cities of the former French East Africa with this agreeable carcinogen, should be given an entire warehouse of last cigarettes.

Still trailed by the Japanese photographer, Harare strode towards the beach. Had one of the dry wells miraculously yielded water for this threadbare redeemer? His thin arms, touching only at the wrists, were pointing to me, making an assegai of his body. I sat up and tried to straighten my blood-stained shirt. The guerillas had turned their backs on me, in a way that I had witnessed on their previous visits. When they no longer bothered to guard their prisoners it was a certain sign that they were about to dispense with them. Only the twelve-year-old sat behind me on the beach, her fierce eyes warning me not even to look at the bandage I had wrapped around her foot. I remembered Harare’s pained expression when he gazed into my cell at the police barracks, and his murmured reproach, as if once again I had wilfully betrayed myself.

‘You were to leave Port-la-Nouvelle, doctor. We made an agreement.’ He seemed unable to grasp my real reasons for clinging to this abandoned town beside the fossil lake. ‘Why do you need to play with your own life, doctor?’

‘There’s the dispensary – it must stay open as long as there are patients. I treated many of your men this morning, General. In a real sense I’m helping your war effort.’

‘And when the government forces come you will help their war effort. You are a strategic asset, Dr Mallory. Captain Kagwa will kill you if he thinks you are useful to us.’

‘I intend to leave. It seems time to go.’

‘Good. This obsession with underground water – your career has suffered so much. You always have to find the extreme position.’

‘I shall be thinking about my career. General.’

‘Your real career, not the one inside your head. It may be too late …’

The radios were playing more loudly. A young guerilla, his nostrils plugged with pus from an infected nasal septum, danced towards me, eyes fixed knowingly on mine, his knees tapping within a few inches of my face. I remembered the Japanese woman’s question, and its curious assumption that I had contrived this exercise in summary justice, among the beer cans and pornographic magazines on this deserted beach at the forgotten centre of Africa, and that I had already decided on my own fate.

3 (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

The Third Nile (#u5f39b0b7-882f-5752-a843-9ac082793201)

The guerilla unit had emerged from the forest at nine that morning, soon after the government spotter plane completed its daily circuit of Lake Kotto. During the night, as I lay awake in the trailer parked behind the health clinic, I listened to the rebel soldiers moving through the darkness on the outskirts of Port-la-Nouvelle. The beams of their signal torches touched the window shutters beside my bunk, like the antennae of huge nocturnal moths. Once I heard footsteps on the gravel, and felt a pair of hands caress the steel framework of the trailer. For a few seconds someone gently rocked the vehicle, not to disturb my sleep, but to remind me that the next day I would be shaken a little more roughly.

By dawn, as I drove my jeep to the drilling site, the town was silent again. However, as I opened my bottle of breakfast beer on the engine platform of the rig I saw the first of the guerillas guarding the steps of the police barracks, and others moving through the empty streets. Beyond the silent quays, in the forecourt of the looted Toyota showrooms, Harare stood with his bodyguard among the slashed petrol pumps, his feet shifting suspiciously through the shards of plate glass.

For all his ambitious dreams of a secessionist northern province, Harare was chronically insecure. A sometime student of dentistry at a French university, he had named himself after the capital of a recently liberated African nation, like the other four Generals in the revolutionary front, none of whom commanded more than a hundred disease-ridden soldiers. But his socialist ideals travelled lightly with a secondary career of banditry and arms smuggling across the Chad border. With the drying out of the lake and the virtual death of the Kotto River – its headwaters were now little more than a string of shallow creeks and meanders – he had decided to extend his domain to Port-la-Nouvelle, and impose his Marxist order on its vandalized garages and ransacked radio stores.

Above all, Harare detested the drilling project, and anyone like myself involved in the dangerous attempt to tap the sinking water table and irrigate the cooperative farms on which the bureaucrats at the Institut Agronomique had squandered their funds. The southward advance of the desert was Harare’s greatest ally, and water in any form his sworn enemy. The changing climate and the imminent arrival of the Sahara had led to the abandonment of Lake Kotto by the government forces. Most of the population of Port-la-Nouvelle had left even before my own arrival six months earlier as physician in charge of the WHO clinic. Within a week Harare’s guerillas had sabotaged the viaduct of galvanized iron which carried water from the drilling pumps to the town reservoir. The Belgian engineer directing the work had been wounded during the raid. Hoping to salvage the project, I had tried to take his place, but the African crew had soon given up in boredom. The few tobacco workers who remained had packed their cardboard suitcases with uncured leaf and taken the last bus to the south.

None of this, for reasons I should already have suspected, discouraged me in any way. With few patients to care for, I turned myself into an amateur engineer and hydrologist. Before his evacuation in the police ambulance the Belgian manager had despairingly shown me his survey reports. Ultrasonic mapping by the Institut geologist suggested that the enfolding of limestone strata two hundred feet below Lake Kotto had created a huge underground aquifer flowing from Lake Chad. This subterranean channel would not only refill Lake Kotto but irrigate the surrounding countryside and make navigable the headwaters of the Kotto River.

The dream of a green Sahara, perhaps named after myself, that would feed the poor of Chad and the Sudan, kept me company in the ramshackle trailer where I spent my evenings after the long drives across the lake, hunting the underground contour lines on the survey charts that sometimes seemed to map the profiles of a nightmare slumbering inside my head.

However, these hopes soon ran out into the dust. None of the six shafts had yielded more than a few hundred gallons of gas-contaminated brine. The line of dead bores stretched across the lake, already filling with milled fish bone. For a few weeks the wells became the temporary home of the nomads wandering westwards from the famine grounds of the Southern Sudan. Peering into the bores during my inspection drives, I would find entire families camped on the lower drilling platforms, squatting around the bore-holes like disheartened water-diviners.

Yet even then the failure of the irrigation project, and the coming of the Sahara, had merely spurred me on, lighting some distant beacon whose exact signals had still to reach me. Chance alone, I guessed, had not brought me to this war-locked nation, that lay between the borders of Chad, the Sudan and the Central African Republic in the dead heart of the African continent, a land as close to nowhere as the planet could provide.

Each morning, as I stepped from my trailer, I almost welcomed the sharper whiteness of the dust which the night air had washed against the flattened tyres. From the tower of the drilling rig I could see the thinning canopy of the forest. At Port-la-Nouvelle the undergrowth beneath the trees was still green, but five miles to the north, where the forest turned to savanna, the network of streams which had once filled Lake Kotto was now a skeleton of silver wadis. Day by day, the desert drew nearer. There was no great rush of dunes, but a barely visible advance, seen at dusk in the higher reflectivity of the savanna, and in the faded brilliance of the forest along the river channels, like the lustre of a dead emerald from which the light has been stolen.

As I knew, the approach of the desert had become an almost personal challenge. Using a variety of excuses, I manoeuvred the manager of WHO’s Lagos office into extending my three-month secondment to Port-la-Nouvelle, even though I was now the town’s only possible patient. Nonetheless my attempts to find water had failed hopelessly, and the dust ran its dark tides into my bones.

Then, a month before Harare’s latest incursion, all my frustration had lifted when a party of military engineers arrived at Port-la-Nouvelle. They commandeered the drilling project bulldozer, pressganged the last members of the rigging crew, and began to extend the town’s weed-grown airstrip. A new earth ramp, reinforced with wire mesh, ran for a further three hundred yards through the forest. From the small control tower, a galvanized iron hut little bigger than a telephone booth, I gazed up at the eviscerated jungle. I imagined a four-engined Hercules or Antonov landing here loaded with the latest American or Russian drilling equipment, hydrographic sounders, and enough diesel oil to fuel the irrigation project for another year.

But rescue was not at hand. A light aircraft piloted by a Japanese photographer landed soon after the airstrip extension was complete. This mysterious young woman, who camped in a minute tent under the wing of her parked aircraft, strode around Port-la-Nouvelle in her flying suit, photographing every sign of poverty she could find – the crumbling huts, the sewage rats quarrelling over their kingdom, the emaciated goats eating the last of the tobacco plants. She ignored my modest but well-equipped clinic. When I invited her to visit the maternity unit she smiled conspiratorially and then photographed the dead basset hound of the Belgian manager, run down by the military convoys.

Soon after, the engineers left, without returning the bulldozer, and all that emerged from the wound in the forest was General Harare and his guerilla force, to whom Miss Matsuoka attached herself as court photographer. I assumed that she was one of Harare’s liberal sympathizers, or the field representative of a Japanese philanthropic foundation. Meanwhile the irrigation project ground literally to a halt when the last of the diamond bits screwed itself immovably into the sandstone underlay. I resigned myself to heeding the heavy-handed advice of the local police chief. I would close the clinic, abandon my dreams of a green Sahara, and return to Lagos to await repatriation to England. The great aquifer beneath Lake Kotto, perhaps an invisible tributary of a third Nile, with the power to inundate the Sudan, would continue on its way without me, a sleeping leviathan secure within its limestone deeps.

4 (#ulink_0d8e2056-b4ba-5e9d-8a00-586c49d2466a)

The Shooting Party (#ulink_0d8e2056-b4ba-5e9d-8a00-586c49d2466a)

Fires burned fiercely across the surface of the lake, the convection currents sending up plumes of jewelled dust that ignited like the incandescent tails of immense white peacocks. Watched by Harare and the Japanese photographer, two of the guerillas approached the last of the drilling towers. They drained the diesel oil from the reserve tank of the engine, and poured the fuel over the wooden steps and platform. Harare lit the cover of a film magazine lying at his feet, and tossed it on to the steps. A dull pulse lit the oily timbers. The flames wavered in the vivid light, uncertain how to find their way back to the sun. Tentatively they wreathed themselves around the cluster of steel pipes slung inside the gantry. The dark smoke raced up this bundle of flues, and rapidly dispersed to form a black thunderhead.

Harare stared at this expanding mushroom, clearly impressed by the display of primitive magic. Sections of the burning viaduct collapsed on to the lake-bed, sending a cascade of burning embers towards him. He scuttled backwards as the glowing charcoal dusted his heels, like a demented dentist cavorting in a graveyard of inflamed molars, and drew a ribald cheer from the soldiers resting on the beach. Lulled by the smoke from the cigarette factory, they lay back in the sweet-scented haze that flowed along the shore, turning up the volume of their cassette players.

I watched them through the din and smoke, wondering how I could escape from this band of illiterate foot-soldiers, many of whom I had treated. Several were suffering from malnutrition and skin infections, one was almost blind from untreated cataracts, and another showed the clear symptoms of brain damage after childhood meningitis. Only the twelve-year-old squatting behind me among the beer bottles and aerosol cans seemed to remain alert. She ignored the music, her small hands clasped around the breech and trigger guard of the antique rifle between her knees, watching me with unbroken disapproval.

Hoping to appease her in some way, I reached out and pushed away the rifle, a bolt action Lee-Enfield of the type I had fired in the cadet training corps of my school in Hong Kong. But the girl flinched from my hand, expertly cocked the bolt and glared at me with a baleful eye.

‘Poor child … all right. I wanted to fasten your dressing.’

I had hoped to loosen the bandage, so that she might trip if I made a run for it. But there were shouts from the quay above our heads – a second raiding party had appeared and now swept down on to the beach, two of the guerillas carrying large suitcases in both hands. Between them they pushed and jostled two men and a woman whom they had rounded up, the last Europeans in Port-la-Nouvelle. Santos, the Portuguese accountant at the cigarette factory, wore a cotton jacket and tie, as if expecting to be taken on an official tour. As he stepped on to the beach he touched the hazy air with an officious hand, still trying to calculate the thousands of cigarettes that had produced this free communal smoke. With the other arm he supported the assistant manager of the Toyota garage, a young Frenchman whose height and heavy build had provoked the soldiers into giving him a good beating. A bloody scarf was wrapped around his face and jaw, through which I could see the imprint of his displaced teeth.

Behind them came a small dishevelled woman, naked except for a faded dressing-gown. This was Nora Warrender, the young widow of a Rhodesian veterinary who had run the animal breeding station near the airstrip. A few months before my arrival he had been shot by a gang of deserting government soldiers, and died three days later in my predecessor’s bed at the clinic, where his blood was still visible on the mattress. His widow remained at the station, apparently determined to continue his work, but on impulse one day had opened the cages and released the entire stock of animals. These rare mammals bred for European and North American zoos had soon been trapped, speared or clubbed by the townspeople of Port-la-Nouvelle, but for a few weeks we had the pleasure of seeing the roofs of the tobacco warehouses and garages, and the balconies of the police barracks, overrun by macaques and mandrills, baboons and slow lorises.

When a frightened marmoset took refuge inside the trailer, I tricked the nervous creature into my typewriter case and drove it back to the breeding station. The large dusty house sat in the bush half a mile from the airstrip and seemed almost derelict. The cage doors were open to the air, and rotting animal feed lay in open pails, pilfered by ferocious rats. Mrs Warrender roamed from window to window of the looted house. A slim, handsome woman with a defensive manner, she received me formally in the gloomy sitting-room, where a local carpenter was attaching steel bars to the window frames.

Mrs Warrender had discharged the male servants, and the house and its small farm were now staffed by half a dozen African women. She called one of the women to her, a former cashier at the dance hall who had been named Fanny by the French mining engineers. Mrs Warrender held her hand, as if I were the ambassador of some alien tribe capable of the most bizarre and unpredictable behaviour. Seeing my typewriter case, she assumed that I was embarking on a secondary career as a journalist, and informed me that she did not wish to recount her ordeal for the South African newspapers. I then produced the marmoset, which sprang into her arms and gave me what I took to be a useful reputation for the unexpected.

A week later, when she visited the dispensary in Port-la-Nouvelle, I assumed that she wanted to make more of our acquaintance – before her husband’s death, Santos told me, she had been a good-looking woman. In fact she had merely wanted to try out a new variety of sleeping pill, but without intending to I had managed to take advantage of her. Our brief affair of a few days ended when I realized that she had not the slightest interest in me and had offered her body like a pacifier given to a difficult child.

Watching her stumble among the beer bottles on the beach, face emptied of all emotion, I assumed that she had seen Harare’s men approach the breeding station and in a reflex of panic had gulped down the entire prescription of tranquillizers. She blundered between the gunmen, trying to support herself on the shoulders of the two guerillas in front of her, who carried their heavy suitcases like porters steering a drunken guest to a landing jetty. They shouted to her and pushed her away, but a third soldier put his arm around her waist and briefly fondled her buttocks.

‘Mrs Warrender …!’ I stood up, determined to help this distraught woman. Behind me, the twelve-year-old sprang to her feet and began to jabber in an agitated way, producing a stream of choked guttural noise in a primitive dialect. I seized the rifle barrel and tried to cuff her head, but she pulled the weapon from my hands and levelled it at my chest. Her fingers tightened within the trigger guard, and I heard the familiar hard snap of the firing pin.

Sobered by the sound, and for once grateful for a defective cartridge case, I stared into the wavering barrel. The girl retreated up the beach, dragging her bandage over the sand, challenging me to strike her.

Ignoring her, I stepped over the legs of the guerillas lounging by their radios. Santos and the injured Frenchman were being backed along the beach to the tobacco wharf, whose heavy teak pillars rose from the debris of cigarette packs like waiting execution posts.

‘Mrs Warrender …?’ I held her shoulders, but she shivered and shook me away like a sleeper refusing to be roused. ‘Have they taken your women? I’ll talk to Harare – he’ll let them go …’

The air was silent. The guerillas had switched off their radios. Plumes of tarry smoke drifted from the gutted shells of the drilling towers, and threw shadows like uncertain pathways across the white surface of the lake. By some trick of the light, Harare seemed further away, as if he had decided to distance himself from whatever happened to his prisoners. The soldiers were pushing us towards the tobacco wharf. They jostled around us, cocking their rifles and hiding their eyes below the peaks of their forage caps. They seemed shifty and frightened, as if our deaths threatened their own sense of survival.

The Japanese photographer ran towards us through the billows of smoke. Seeing her concerned eyes, I realized for the first time that these diseased and nervous men were about to shoot us.

5 (#ulink_72bc1608-762f-5a31-b303-f7096a31c0bd)

Fame (#ulink_72bc1608-762f-5a31-b303-f7096a31c0bd)

Signal flares were falling from the air, like discarded pieces of the sun. The nearest burned through its metal casing thirty yards from the beach where I stood with Mrs Warrender, its mushy pink light setting fire to an old newspaper. The spitting crackle was drowned by the noise of a twin-engined aircraft which had appeared above the forest canopy. It flew north-east across the lake, then banked and made a laboured circuit of Port-la-Nouvelle. The drone of its elderly engines shivered against the galvanized roofs of the warehouses, a vague murmur of pain. Looking up, I could see on the Dakota’s fuselage the faded livery of Air Centrafrique.

Harare and his guerillas had gone, vanishing into the forest on the northern side of Lake Kotto. The radios and cassette players lay on the beach, thrown aside in their flight. One of the radios still played a dance tune broadcast from the government station in the capital. Beside it rested an open suitcase, Nora Warrender’s looted clothes spilling across the lid.

She pushed my arm away and knelt on the sand. She began to smooth and straighten the garments, her neat hands folding a silk ball gown. Draping this handsome robe over her arm like a flag, she walked past me and began to climb the beach towards the jetty.

‘Nora … Mrs Warrender – I’ll drive you home. First let me give you something in the dispensary.’

‘I can walk back, Dr Mallory. Though I think you should take something. Poor man, everything you’ve worked for has gone to waste.’

Her manner surprised me; a false calm that concealed a complete rejection of reality. She seemed unaware that we both had very nearly been shot by Harare’s men. I was still shaking with what I tried to believe was excitement, but was almost certainly pure terror.

‘Don’t pull my arm, doctor.’ Mrs Warrender eased me away with a weary smile. ‘Are you all right? Perhaps someone can help you back to the clinic. I suppose we’re safe for the next hour or so.’

She pointed to the dirt road along the southern shore of Lake Kotto. A small convoy of government vehicles, a staff car and two trucks filled with soldiers, drove towards Port-la-Nouvelle. Clouds of dust rose from their wheels, but the vehicles moved at a leisurely pace that would give Harare and his men ample time to disperse. At the entrance to the town, by the open-air cinema, the convoy stopped and the officer in the staff car stood behind the windshield and fired another flare over the lake.

Shielding her eyes, Mrs Warrender watched the transport plane drone overhead. The pilot had identified the landing strip and was aligning himself on to the grass runway. Mrs Warrender stared at the charred hulks of the drilling towers, which stood on the lake like gutted windmills.

‘A shame, doctor – you tried so hard. I imagine you’ll be leaving us soon?’

‘I think so – the only patients I have here spend their time trying to kill me. But you aren’t staying, Nora—?’

‘Don’t give up.’ She spoke sternly, as if summoning some wavering dream. ‘Even when you’ve left, think of Lake Kotto filled with water.’

Without looking at me again, she crossed the road and set off towards the breeding station, the ball gown over her arm. The convoy of soldiers approached the police barracks, guns trained on the broken windows. Santos and the Frenchman ignored the vehicles and the shouting soldiers, and walked back to their offices, refusing my offers of help. I knew that they considered my medical practices to be slapdash and unhygienic. Shrugging off the pain in his swollen jaw, the Frenchman began to sweep away the glass in front of the Toyota showroom.

The Dakota circled overhead, its flaps lowered for landing. I strode towards the clinic, deciding to seal the doors and shutters of the dispensary before an off-duty platoon of the government soldiers began to search for drugs. The two trucks rolled past, their wheels driving a storm of dust against the windows of the beer parlour. As they passed Mrs Warrender, the soldiers hooted at the silk gown draped over her arm, assuming that this was some elaborate nightdress that she was about to wear for her lover.

I watched her moving with her small, determined steps along the verge, dismissing the young soldiers with a tired wave. I imagined lying beside Nora Warrender in her silk robe, watched perhaps by a stern-faced bridal jury of her servant women. Fanny and Louise and Poupee would be watching for the first drop of my blood, not my bride’s. Then a battered staff car, its plates held together by chicken wire, stopped in the entrance to the clinic. A large hand seized my elbow and a handsome African in a parade-ground uniform, Captain Kagwa of the national gendarmerie, shouted through the aircraft noise.

‘She’s not for you, doctor! For pleasure you’ll have to sit with me!’

‘Captain Kagwa … For once you’re on time …’

‘On time? My dear doctor, we were delayed. Where’s Harare? How many men did he have?’

‘More than three platoons. Don’t worry, you gave them enough warning to escape.’ I pointed to the trucks heading towards the airstrip. ‘Why all this military action? I thought you’d already stolen everything in Port-la-Nouvelle?’

‘Doctor, I don’t want anything from you, not even your water. I’ve brought you something precious. What you Europeans really understand.’

‘Drilling bits, Captain?’

‘Drilling—?’ Kagwa pulled me into the rear seat of the jeep, where I sat among the field radios and ammunition boxes. ‘I’m talking about something real, doctor, something you can hold in your hand, that’s not going to run through your fingers like water. I’m talking about fame.’

Fame? Had I been shot, along with Santos and Mrs Warrender, the news would scarcely have made the morning bulletin on the government radio station. I assumed that this was some complex game of the Captain’s – perhaps Harare was about to be betrayed by his own men and I would be called upon to identify the body as it lay in state at the Toyota showroom. Since my failed courtship of Mrs Warrender, I had grown to know this amiable but unpredictable police chief more closely than anyone else at Port-la-Nouvelle. A huge and often clumsy man, well over six feet tall, Kagwa was capable of surprising delicacy of mind. He was a modest amateur pianist, and had tried patiently to teach me the rudiments of the keyboard on Santos’s upright.

A fanatic for self-improvement, Kagwa spent his spare time listening to a library of educational cassettes on politics, law and economics. One evening in Port-la-Nouvelle, when the French mining engineers had run riot through the beer parlours, I tried to compliment him by remarking piously that he and I were the only sober and responsible people in the town. He had clasped my shoulders in his immense hands and said, with great earnestness: ‘Doctor, you are not sober. You are not even responsible. No responsible man would search for water at Lake Kotto – I could arrest you tomorrow. You are Noah, doctor, waiting for rain, Noah without an ark.’

A brief cloudburst would have been welcome as we reached the airstrip. The Dakota had already landed, and was taxiing through its own dust, engines setting up a storm of white soil. The two trucks filled with soldiers drew up alongside the control tower. One squad set off to patrol the airstrip perimeter, weapons raised to the forest canopy as if the soldiers expected Harare and his guerillas to be climbing into the sky. A second platoon formed an honour guard, heels stamping as they dressed off in two files. While they presented arms I saw that the entire scene was being filmed by the Japanese photographer. From the cockpit of her light aircraft Miss Matsuoka had removed a chromium suitcase packed with lenses and filters. Mounting a small cine-camera on a tripod, she filmed the Dakota as it lumbered up and down the earth strip, casting clouds of dust and dirt over the tractor parked beside the trees at the eastern end of the runway.

At last, having convinced himself that he had landed, the African pilot shut down the engine. The noise faded, and the co-pilot’s window opened to the air. A blond-haired man in a safari jacket, with a deep sun-tan that was more electric than solar, leaned from the window and gave a series of encouraging waves, apparently returning the cheers of a huge welcoming party. He repeated the performance as Miss Matsuoka, face pressed to the eyepiece of the hand-held camera, ducked under the starboard wing. She crept along the fuselage, her lens taking in every capped tooth in the man’s confident and wolflike smile.

Already the cargo doors had opened, and two crew men lowered a metal step to the ground. Their overall pockets carried a distinctive emblem that seemed to be both a religious symbol and the logo of a television station.

‘Who are these people?’ I asked Captain Kagwa as we stepped from the jeep and shook the dust from our clothes. ‘Are they evangelists? Or some sort of missionary group?’

‘Our saviour, certainly.’ Kagwa saluted the aircraft with an ironic flourish. ‘Professor Sanger brings hope to our doorstep, salvation for the poor and hungry of Lake Kotto, comfort for the bush doctor …’

The blond-haired man stood in the doorway of the cargo hold. He was in his mid-forties, and had the reassuring but devious manner of a casino operator turned revivalist preacher. He bent down and greeted Captain Kagwa with a generous handshake, while giving his real attention to the Japanese photographer, who was reloading her camera beneath the starboard wing tip. When she was ready he ruffled his hair and then brought his hands together in a snapping gesture which I first assumed was a stylized religious greeting, but in fact was a clapperboard signal. As the camera turned, he posed beside two large sacks which the flight crew had manhandled into the hatchway. He composed his features into a tired but pensive gaze, and allowed a quirky smile, at once vulnerable but determined, to cross his sharp mouth. This well-rehearsed grimace, a tic I had seen before somewhere, cleverly erased all traces of his quick intelligence from his face. Only his eyes remained evasive, looking out at the indifferent forest wall with a curious blankness, like those of an unrecognized celebrity forced to return the stares of a foreign crowd. When Miss Matsuoka called to him, he quickly slipped on a large pair of sunglasses.

‘Right, Professor Sanger – I will wait for the poor people to receive your gifts …’

The Japanese woman had completed her shot, and was thanking Captain Kagwa, who had clearly relished the attentions of her lens. I left the jeep and walked to the wingtip of the Dakota, running my hand against the weather-worn trailing edge of this elderly aircraft. I now remembered Professor Sanger, a sometime biologist turned television popularizer. He had enjoyed a brief celebrity ten years earlier with a series of programmes that sought to demonstrate the existence of psychic phenomena in the animal world. The migration of birds, the social behaviour of ants and bees, the salmon’s immense journey to its spawning grounds, were all attributed to the presence of extra-sensory powers distributed throughout the biological kingdom, but repressed in Homo sapiens. As a newly qualified houseman doing my year on the wards in a London hospital, I would see him on the television set in the junior doctors’ common room. Of mixed Australian and German ancestry, Sanger had perfected the rootless international style of an airline advertisement, which his audiences took for objectivity. After a day spent in the emergency unit, treating road accident casualties and the victims of strokes and heart attacks, I would sit exhausted in the debris of the common room and watch this scientific smiler holding forth from a rockpool in the Great Barrier Reef or an anthill in the Kalahari.

Fortunately, his success was short-lived. He soon exposed himself to ridicule when he claimed that plants, too, could communicate with one another and appeared in a televised experiment in which the gardeners of Britain rose at dawn and urged their hollyhocks and lupins to deny the sun. After this fiasco Sanger began a second career in Australian television, but he soon became involved with dubious video and publishing ventures, popup books and filmed histories of the Yeti and Bigfoot.

‘Dr Mallory …’ Captain Kagwa signalled to me. I was being summoned to meet the great man, who was already in conference with his production staff – a small team of European engineers, and a scholarly young Indian frowning over his pocket calculator, whom I took to be Sanger’s scientific researcher. Behind them were two African journalists from the government information office, gazing sceptically at the weed-grown airstrip and the silent forest.

‘Doctor …’ Sanger clasped my injured hand in a strong grip, greeting me with deep respect as if I were Livingstone himself or even, conceivably, that ultimate marvel, a member of the ordinary public. ‘Doctor, Captain Kagwa tells me that I have saved your life.’

I was unable to think of an adequate reply to this – it occurred to me that if I knelt at Sanger’s feet he would have been unaware of any irony. All the more annoying was the fact that the statement was literally true.

To add to my irritation, Captain Kagwa interjected: ‘The guerilla attack, doctor – it was fortunate for you that the television plane arrived on time.’

Sanger modestly dismissed this. ‘We have so many lives to save. There are mouths to feed, Africa is still starving, the world is starting to forget. The selfless work of people like yourself, Dr Mallory, needs to be brought into every living-room.’ Sanger pointed to the cargo hold of the aircraft, where I could see the sections of a small satellite dish among the grain sacks. Electronic equipment, lights and reels of wire were stowed between the seats. ‘We have complete studio facilities here. Africa Green, the television charity to which I have donated my time, has satellite links with the major Japanese networks. In fact, doctor, we thought of using you in our film.’

‘You would bring me into every Japanese living-room?’

‘Your work here, doctor, and your escape from death.’ Sanger paused, looking me up and down in a shrewd but not unfriendly assessment. I was certain that he saw me as little more than a scruffy bush doctor, in my dusty cotton shorts, lumpy army boots and blood-stained shirt, the backwoods physician stuck in my ways and unable to accept the opportunities of the media landscape. Yet he may have grasped that he needed me. ‘But the important task is to feed the mouth of Africa. We have five tons of rice here, bought with funds donated by West German television viewers. It’s only a small start … Will you help us, doctor?’

‘I’d like to – it’s very generous, and the charities have done enormous good. But one problem is that the people here don’t eat rice. Their diet is sorghum and manioc. The second is that there aren’t any people – they fled months ago, as Captain Kagwa should have told you.’

‘Well, they may be brought back.’ Kagwa gestured to the empty forest, uncomfortable with my churlish response, ‘It would be good for the Lake Kotto project, doctor.’

‘Fair enough. We’ll bring them back. I’m sure they would like to go on Japanese television – perhaps you should starve them a little first?’

‘Professor—!’ The Indian assistant shouted in anger. Bookish and trembling, he stepped protectively between us, his eyes searching wildly for the Dakota’s pilot and an instant take-off to a more welcoming site. ‘Such a remark betrays Dr Mallory’s profession. In the context –’

‘It’s all right, Mr Pal. The doctor is naturally bitter. He was brutally mistreated …’

I liked this earnest young Indian, and tried to pacify him. ‘That wasn’t sacrilege – not everyone in Africa is starving. The people of Lake Kotto have always been well-nourished. The problem here is the shortage of water. And the Sahara. I’m afraid you’ve lengthened the wrong runway.’

Captain Kagwa was about to intercede – I assumed he had been thinking of his future political career when he invited this small mercy mission to Port-la-Nouvelle – but Sanger suddenly took my arm. In a gesture of surprising intimacy, he steered me along the wing, unconcerned that the blood from my hand was marking his jacket. He was well-groomed, but I noticed that his teeth were riddled with caries, a surprising defect in a television performer. At close quarters his blond hair and deep suntan failed to mask an underlying seediness, and the look of immanent failure that his recent face-lift would never disguise. The subcutaneous fat had been cut away beneath the lines of his cheekbones, and his gaunt jaw was carried in a set of muscular slings. Whenever he switched off his spectral smile his handsome face seemed to die a little.

‘You must help me, doctor, as long as you are here. Captain Kagwa tells me you are leaving. Stay a few more days. You and I can deal with the Sahara later. Just now I need to show the people in Europe that I am trying.’

‘I understand. Why not go to Chad or the Sudan? You could do real good there.’

‘It’s not so easy – these regimes are choosy. Oxfam, UNICEF, the other big agencies are there. This was all I could find. I know – even my disaster area is a disaster.’

He wiped his forehead on his jacket sleeve, transferring a smear of my blood to his right temple. The first sections of a miniature television studio were being unloaded from the plane – lights, monitor screens like pickled egg yolks, sections of the satellite dish, consoles of switches, and a trio of cameras of various sizes. Only the sight of this electronic equipment seemed to calm Sanger.

‘Look, doctor, perhaps they don’t eat rice here – thousands of people in Düsseldorf and Hamburg paid for these sacks with small donations. This plane charter, I have to rent microwave links, millions of yen per kilometre, a lot of expense from my own pocket. But it’s a big chance for me … Perhaps my last chance. I have only Mr Pal and Miss Matsuoka to help me – they’re my ears and my eyes. All I need is a few pictures for the evening television news …’

This display of frankness and concern was so bogus that I almost believed it. Sanger had spent so long in the worlds of publicity and self-promotion that only the calculated gesture was sincere. A spontaneous insincerity was as close as one could come to the truth. Mere honesty would have seemed contrived and dubious to him, a surrender to brute feelings. The bad teeth, the antique aircraft, the fifty sacks of rice, suggested that the chief recipient of any aid was Sanger himself. It was his television career he hoped to rescue with this threadbare mercy mission. His choice of Port-la-Nouvelle marked only his own despair. The prime sites – Ethiopia, Chad, the Sudan – had been allocated to the most powerful television interests, the huge American networks and the British record companies. At the same time, I felt a certain concern for him. In many ways he was more in need of help than the vanished inhabitants of Port-la-Nouvelle. In practical terms, I had already made a small contribution to Sanger’s effort. It was my tractor which had helped to clear the forest and extend the runway.

‘Professor Sanger, take care!’ Mr Pal, the Indian adviser, pushed me aside and placed an arm around Sanger’s head, as if to shield his eyes from an unpleasant spectacle. Soldiers were running across the airstrip, some taking shelter behind the control tower, others shouting to each other as they crouched beneath the engines of the aircraft.

A single rifle shot sounded from the eastern end of the runway, its harsh report magnified by the forest wall. Hundreds of cuckoo-shrikes rose from the canopy, colliding with each other in their panic as they circled the lake.

Had Harare and his men returned? I knelt behind the sacks of rice, as the pilot and Mr Pal hauled Sanger into the cargo hold. The soldiers guarding the perimeter of the airstrip waved across the runway, pointing to the undergrowth that surrounded the tractor. They aimed their rifles at the deep grass, as if about to flush out a forest boar, or one of the released residents of Mrs Warrender’s breeding station, unable to cope with the rigours of life in the wild and pining for the peace and freedom of captivity.

I followed Captain Kagwa as he strode down the runway. The soldiers had found their prey in the undergrowth. Rifles raised like spears, they jabbed and prodded a small, bloodied mammal that scuffled at their feet in the long grass.

‘Doctor, they’ve caught a guerilla!’ Camera at the ready, Miss Matsuoka ran past me, almost twisting her ankle in the dusty ruts left by the Dakota.

The soldiers stepped back as Kagwa reached them, lowered their rifles and gesticulated at the figure beside their feet. Kneeling in the long grass, whose blades were wet with the blood from her nose and mouth, was the twelve-year-old girl who had guarded me on the beach. Unable to keep up with Harare and his escaping force, she had been abandoned in the tract of forest that separated the airstrip from the shores of Lake Kotto. She had thrown away both the Lee-Enfield rifle and her camouflage jacket, and wore only her ragged shorts and a green singlet. She sat on the ground as the rifle barrels bruised her cheeks and forehead. Wiping the blood from her nose, she tied and untied the bandage around her infected foot. When she saw me approach she looked up with the same hostile eyes that had steered me on to the beach two hours earlier. Small and hungry, fidgeting nervously with her filthy bandage, she made it clear that the reversal of our fates in no way altered her judgement of me, even though a rifle stock would crush her skull in a matter of seconds.

‘Dr Mallory – come with me.’ Captain Kagwa pushed through his men. He bent down and slapped the girl, stunning her with a blow. He held her cropped head in a huge hand and tilted it back. ‘You recognize her? She was with Harare?’

Miss Matsuoka brushed past me. ‘Yes, Captain – she tried to kill the doctor.’

‘Well, doctor?’

The bandage flicked to and fro as a pair of small eyes watched me from between Kagwa’s fingers.

‘I haven’t seen her before.’ I tapped Kagwa’s elbow, hoping that he would order the soldiers away before they began their sport. ‘This is a different girl.’

‘But, Captain—!’ Miss Matsuoka began to protest, and then noticed the satellite dish being erected beside the Dakota. Her attention veering away, she beckoned to us both. ‘Back to the plane – Professor Sanger is setting up the interviews, Captain.’

The girl shook her head free from Kagwa’s grip. He reached down and threw her backwards into the grass, where one of the soldiers kicked her with his rubber boot. She scuffled away through the undergrowth, dragging her unravelling bandage like a snakeskin.

I watched her vanish into the trees and said: ‘I’ll take my tractor, Captain. Perhaps your sergeant would drive it for me.’

‘Of course.’ He seemed glad that at last I had something to distance me from my hostility to Professor Sanger. ‘May you find just one gallon of water before you leave, doctor. Enough to wash away all memories of Port-la-Nouvelle.’

6 (#ulink_7cdbb9f9-15ed-5c41-bee0-52272fbc5f11)

The Oak and the Spring (#ulink_7cdbb9f9-15ed-5c41-bee0-52272fbc5f11)

As smoke pumped from its exhaust funnel, the tractor laboured through the soft soil beside the runway extension. I stood a dozen yards in front of the unsteady vehicle, trying to attract the driver’s attention. Confused by the steering levers and by the slow but powerful response of the engine, the sergeant had barely mastered the heavy clutch. The tractor slewed in the soft mud, the metal scoop swinging from side to side. Its scarred blade cut fillets of damp soil from the sloping ground. They curled back beneath the treads and were stamped into the ground by the metal links.

I walked along these rectilinear grids, a trace of the passing imprint of western technology on the African land, as the tractor reversed down the slope. On either side of the runway the army engineers had cleared the forest for a hundred yards, and the uneven ground was a forgotten terrain of mud-filled gulleys, hillocks of pulverized earth, and dumps of flourishing underbrush.

The tractor blundered across this no-man’s land, the driver straining his arms to hold the machine on its course towards the forest road that ran from the eastern end of the airstrip to the shores of Lake Kotto. He climbed the last of the hillocks, and then faced a ramp of compacted earth which the engineers had erected for their supply vehicles. The sergeant throttled up his engine, lowered the scoop and thundered forward in a roar of smoke and oil. The metal blade sank into the ramp, and cut away a huge block of compressed gravel mounted on a section of underlying soil that contained the root-tree of a forest oak.

This immense black core lay partly exposed, like the petrified heart of an extinct bull, or the crown of an underworld deity ripped from the ceiling of a subterranean palace whose arches supported the airstrip, a submerged cathedral of mud. The soil wept through its roots and fell into the dark maw of the cavern below, an open mouth wide enough to swallow a small car.

The sergeant reversed his gears, and briefly cut back his engine. He looked up at me, as I watched from the edge of the runway, clearly expecting me to order him to ignore this obstacle and make a sensible detour around it. But I waved him forward, curious to see how large this root-system might be – clearly the felled tree had been one of the tallest oaks in the forest, sitting for hundreds of years at the water table of Lake Kotto, until cut down to make way for Sanger’s runway extension and his preposterous mission. I felt the ground under my feet, hoping to hear a rumble of subsidence – with luck, the removal of this ancient root would undermine the runway and the Dakota would crash on take-off …

The sergeant worked up his engine, smoke pumping from the exhaust stack behind his head. He engaged the gears and drove forward, gradually forcing the root-crown from the cavity where it rested. To my disappointment, it failed to put up any great fight, but lay passively against the tractor’s scoop, a gnarled mass of dead roots some six feet in diameter. Forced on to its back, it rolled soundlessly into a hollow between two nearby hillocks and expired there in a cloud of sandy dust, a long-dead god of the earth.

I waited as the tractor rumbled forward, its treads easily straddling the cavity below. As the sergeant headed towards the forest path I walked down the earth ramp and peered into the open mouth. Scores of torn roots emerged from the ground-soil, the crop of a strange subterranean plantation. To my surprise, however, a small pool of water had appeared at the base of the cavity. As if leaking from the amputated roots, the dark liquid slowly covered the sandy floor, the last sap of the dead oak irrigating its own grave.

All too aware of the irony that I had at last struck water, I gathered the loose soil between my feet and swept it into the cavity. But the water was already several inches deep, fed from some underground stream, part of an artificial reservoir, I assumed, created by the construction of the airstrip. I gazed down, seeing my own face reflected in the black mirror from which the dead roots of the oak rose to greet me. I kicked a last shower of earth into my reflection and strode down the remains of the ramp, following one of the parallel pathways left by the tractor.

Fifty yards into the forest, I stopped to wait for the tractor’s smoke to dissipate through the trees. Looking back, I could see the pattern of metal tracks stamped into the long bracelets of soil that led to the airstrip.

A thin stream of water, little more than the width of my arm, flowed along the track, carried by the slight gradient that ran down to the lake. While I waited, it crept towards my heels and touched them, moving in a zigzag of lateral and forward movements that seemed to notch up a series of coded messages, computerizing itself around my feet.

An hour later, as I stood on the jetty beside the police barracks, above the beach where the twelve-year-old had tried to kill me, I saw the stream emerge from the forest and make its way down to the drained bed of the lake. It formed a small pool beneath the debris along the beach, nudging at the cigarette packs and beer cans which were already floating on its surface, as if trying to stir this dusty rubbish into a second life.

7 (#ulink_5815e717-99ad-58fc-a3e0-a1891cf8c5f6)

The Impresario of Rubbish (#ulink_5815e717-99ad-58fc-a3e0-a1891cf8c5f6)

Behind my back, a mirror was forming. All morning, as I worked among the packing cases in the looted clinic, I was aware of the vivid reflection from the lake, as if someone had switched on the underwater lights of a swimming pool. For reasons of its own the sun had come closer to Port-la-Nouvelle, perhaps intrigued by the appearance of this dark water that had spent so many aeons within the earth.