Читать онлайн книгу «The Girl Who Couldn’t Read» автора John Harding

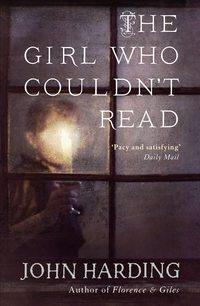

The Girl Who Couldn’t Read

John Harding

A sinister Gothic tale in the tradition of The Woman in Black and The Fall of the House of UsherNew England, The 1890sWhen a young doctor begins work at an isolated mental asylum, he is expected to fall in with the shocking regime for treating the patients. He is soon intrigued by one patient, a strange amnesiac girl who is fascinated by books but cannot read. He embarks upon a desperate experiment to save her but when his own dark past begins to catch up with him, he realises it is she who is his only hope of escape.In this chilling literary thriller from a master storyteller, everyone has something to hide and no one is what they seem.

JOHN HARDING

The Girl Who Couldn’t Read

Copyright (#ulink_eeeb2f69-1e1c-5e40-b7c7-664e2d2dfe5b)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by The Borough Press 2014

Copyright © John Harding 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photograph Susan Fox/Trevillion Images

John Harding asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007324255

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780007562107

Version: 2015-03-18

About the Book (#ulink_6bab9ea3-881f-5160-9bfc-975695322df8)

New England, The 1890s

When a young doctor begins work at an isolated mental asylum, he is expected to fall in with the shocking regime for treating the patients. He is soon intrigued by one patient, a strange amnesiac girl who is fascinated by books but cannot read. He embarks upon a desperate experiment to save her but when his own dark past begins to catch up with him, he realises it is she who is his only hope of escape.

In this chilling literary thriller from a master storyteller, everyone has something to hide and no one is what they seem.

Praise for John Harding: (#ulink_aae10e31-a884-5201-a09e-6e93ca3ed01f)

‘A tight gothic thriller … unbearably tense’

Financial Times

‘Genuinely exciting and shocking’

Independent

‘The Girl Who Couldn’t Read will prove to be a delight for anyone with a love of Victorian fiction, the work of Sarah Waters or who takes pleasure in a bloody good story well told. Harding is a master storyteller and has produced another classic’

Me And My Big Mouth

‘Brilliantly creepy’

Daily Mirror

‘Hugely gripping … the most perfect ending in fiction, I swear’

Heartsong

‘A tour de force’

Daily Mail

‘Full of disturbing atmosphere, mysterious characters, and a page-turning plot. I flew through it’

A Literary Mind

‘Thoroughly ingenious and captivating … a scarily good story’

The Oxford Times

‘Nothing prepares you for the chillingly ruthless finale’

The Times

‘The tension is palpable. Leaves the reader gasping’

We Love This Book

‘A fantastic gothic horror story set in an asylum for women in 1890’s New England. It will grab you, excite you and leave you eager for more’

The Moustachioed Reader

‘Harding winds things nice and tight … brilliant tension … The eeriness pervades like a dank fog’

New Zealand Herald

Dedication (#ulink_36d3fbde-e0f7-5e79-bcb9-6b8bb8b484b1)

For the book-lovers of Brazil

Contents

Cover (#uf2c90173-c468-58ee-bbd5-54ba8bfc55a7)

Title Page (#u5ff65be2-cf97-5253-9f66-8356a7887534)

Copyright (#u36fe7e96-c9ba-5d67-8134-7486d6ad1a30)

About the Book (#u780268f1-4b85-5bf0-82af-bfd37b917b92)

Praise for John Harding (#ua34749c7-740a-5d2a-a19e-0e6ec2fa1dac)

Dedication (#u63c1a19d-f6fa-59b3-862f-31e43b951966)

Chapter 1 (#ucb53aa57-8270-5181-bc2c-2e910ce72eb6)

Chapter 2 (#uf77ca4f0-29e8-5e45-a473-212fa9ce6f67)

Chapter 3 (#u6c968566-e957-5af6-a47a-8fb1bddbbe16)

Chapter 4 (#ue4749a8c-1a40-5bfb-a6ef-81673db7d005)

Chapter 5 (#u449d38c3-b3bb-5b7b-8f50-cd274db3c93d)

Chapter 6 (#u1be679dc-0e18-51c0-a79a-57947b6e6c27)

Chapter 7 (#uedeb3a46-9c4a-502b-9d24-4b97517c17b2)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Read an Extract for Florence and Giles (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by John Harding (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_32e63d9a-50ab-51f0-b245-2b60370505b7)

‘Dr Morgan expects you in his office in ten minutes. I will come and fetch you, sir.’

I thanked her, but she stood in the doorway, holding the door handle, regarding me as though expecting something more.

‘Ten minutes, mind, sir. Dr Morgan doesn’t like to be kept waiting. He’s a real stickler for time.’

‘Very well. I’ll be ready.’

She gave me a last suspicious look, top to toe, and I could not help wondering what it was she saw. Maybe the suit did not fit me so well as I had thought; I found myself curling my fingers over the cuffs of my jacket sleeves and tugging them down, conscious they might be too short, until I realised she was now staring at this and so I desisted.

‘Thank you,’ I said, injecting what I hoped was a note of finality into it. I had played the master often enough to know how it goes, but then again I had been a servant more than once too. She turned, but with her nose in the air, and not at all with the humility of a lackey who has been dismissed, and left, closing the door behind her with a peremptory click.

I gave the room a cursory glance. A bed, with a nightstand, a closet in which to hang clothes, a battered armchair that looked as if it had been in one fight too many, a well-worn writing desk and chair, and a chest of drawers on which stood a water jug and bowl, with a mirror hanging on the wall above it. All had seen better days. Still, it was luxury compared with what I had been used to lately. I went over to the single window, raised the blind fully and looked out. Pleasant lawned grounds beneath and a distant view of the river. I looked straight down. Two floors up and a sheer drop. No way out there, should a person need to leave in a hurry.

I shook off my jacket, glad to be relieved of it for a while, realising now I was free of it that it was a tad too tight and pulled under the arms, where my shirt was soaked with sweat. I sniffed and decided I really should change it before meeting Morgan. I took out and read again the letter with his offer of employment. Then I lifted the valise from the floor, where the maid had left it, onto the bed and tried the locks again, but they would not budge. I looked around for some implement, a pair of scissors or a penknife perhaps, although why I should expect to find either in a bedroom I couldn’t have said, especially not here of all places, where it would surely be policy not to leave such things lying about. Finding nothing, I decided it was no use; my shirt would have to do.

I went over to the chest of drawers, poured some water into the bowl and splashed it over my face. It was icy cold and I held my wrists in it to cool my blood. I looked at myself in the mirror and at once easily understood the serving woman’s attitude toward me. The man staring back at me had a wild, haunted expression, a certain air of desperation. I tried to arrange my hair over my forehead with my fingers and wished it were longer, for it didn’t answer to purpose.

There was a rapping on the door. ‘One moment,’ I called out. I looked at myself again, shook my head at the hopelessness of it all and heartily wished I had never come here. Of course I could always bolt, but even that would not be straightforward. An island, for Christ’s sake, what had I been thinking of? Sanctuary, I suppose, somewhere out of the way and safe, but also – I saw now – somewhere from which it would be difficult to make a quick exit.

More rapping at the door, fast and impatient this time. ‘Coming!’ I shouted, in what I hoped was a light-hearted tone. I opened the door and found the same woman as before. She stared at me with a look that suggested surprise that I had spent so long to accomplish so little.

I found Morgan in his office, seated at his desk, which faced a large window giving onto the spacious front lawns of the hospital. I could well understand how someone might like to look up from his work at such a capital view, but it struck me as odd that a man who must have many visitors should choose to have his back to them when they entered.

I stood just inside the door, looking at that back, ill at ease. He had heard the maid introduce me; he knew I was there. It occurred to me that this might be the purpose of the desk’s position, to establish some feeling of superiority over any new arrival; the man was a psychiatrist, after all.

A good minute elapsed and I thought of clearing my throat to remind him of my presence, although I know a dramatic pause when I come across one, and to wait for my cue before speaking out of turn, so I held my position, all the while conscious of the sweat leaking from my armpits and worrying that it must eventually penetrate my jacket. I did not know if I had another. There was complete silence except for the occasional echo of a distant door banging its neglect and the leisurely scratch of the doctor’s pen as he carried on writing. I decided I would count to a hundred and then, if he still hadn’t spoken, break the silence myself.

I had reached eighty-four when he threw the pen aside, twirled around in his swivel chair and propelled himself from it in almost the same movement. ‘Ah, Dr Shepherd, I presume!’ He strode over to me, grabbed my right hand and shook it with surprising vigour for a man who I saw now was dapper, by which I mean both short in stature and fussily turned out; he had a thin, ornamental little moustache, like a dandified Frenchman, and every hair on his salt-and-pepper head seemed to have been arranged individually with great care. He had spent a good deal more time on his toilette than I had had means or opportunity to do on mine and I felt embarrassed at the contrast.

‘Yes, sir.’

I found myself smiling in spite of my trepidation at the coming audition, my sodden armpits and the state of my face. It was impossible not to, since he was grinning broadly. His cheerful demeanour lifted my spirits a little; it was so greatly at odds with the gloominess of the building.

Finally releasing my hand, which I was glad of, as his firm grip had made me realise it must have been badly bruised in the accident, he stretched out his arms in an expansive gesture. ‘Well, what do you think, eh?’

I assumed he was referring to the vista outside, so, casting an appraising eye out the window, said, ‘It’s certainly a most pleasant view, sir.’

‘View?’ He dropped his arms and the way they hung limp at his sides seemed to express disappointment. He followed my gaze as if he had only just realised the window was there and then turned back to me. ‘View? Why, it’s nothing to the views we had back in Connecticut, and we never even looked at them.’

I did not know what to make of this except that I had come to a madhouse and that if the inmates should prove insane in any degree relative to the doctors, or at least the head doctor, then they would be lunatics indeed.

‘Wasn’t talking about the view, man,’ he went on. ‘You’re not here to look at views. I mean the whole place. Is it not magnificent?’

I winced at my own stupidity and found myself mumbling in a way that served only to confirm this lack of intelligence. ‘Well, to be honest, sir, I’m but newly arrived and haven’t had an opportunity to look about the place yet.’

He wasn’t listening but instead had extracted a watch from his vest pocket and was staring at it, shaking his head and tutting impatiently. He replaced the watch and looked up at me. ‘What’s that? Not looked round? Let me tell you you’ll find it first class when you do. Adapted to purpose, sir, every modern facility for treating the mentally ill a doctor could wish for. Couldn’t ask for a better place for your practical training, sir. Medical school is all very well but it’s in the field you learn your trade. And believe me, it’s a good trade for a young man to be starting out in. Psychiatry is the coming thing, it is the way—’ He stopped abruptly and stared at me. ‘Good God, man, what on earth has happened to your head?’

I reached a hand up to my temple, my natural inclination being to cover it. I had my story ready. I have always found that the extraordinary lie is the one that is most likely to be believed. ‘It was an accident in the city on my way here, sir. I had an unfortunate encounter with a cabriolet.’

He continued to stare at the bump and I could not help arranging my hair in an attempt to conceal it. Sensing my embarrassment, he dropped his eyes. ‘Well, lucky to get away with just a mild contusion, if you ask me. Might have fractured your cranium.’ He chuckled. ‘Let’s hope it hasn’t damaged your brain. Enough damaged brains around here already.’

He walked back to his desk and picked up a piece of paper. ‘Anyway, looking at your application, I see you have an exceptional degree from the medical school in Columbus. And this is just the place to pick up the clinical experience to go with it. Hmm …’ He looked up from the paper and stared at me quizzically. ‘Twenty-five years old, I see. Would have thought you were much older.’

I felt a sudden panic. Why had I not thought about my age? What a stupid thing to overlook! But at least twenty-five was within the realms of possibility. What if it had been forty-five? Or sixty-five? I would have been finished before I started. I improvised a thin chuckle of my own. It’s a useful skill being able to laugh on demand even when up against it.

‘Ha, well, my mother used to say I was born looking like an old man, and I guess I’ve never had the knack of appearing young. My late father was the same way. Everyone always took him for ten years older than he was.’

He raised an eyebrow and peered again at the paper he was holding. ‘I see too you have some –ah – interesting views on the treatment of mental illness.’ He looked up and stared expectantly at me, a provocative hint of a smile on his lips.

I felt the blood rush to my cheeks. The bruise on my forehead began to throb and I imagined it looking horribly livid, like a piece of raw meat. I began to mumble but the words died on my lips. Fool! Why had I not anticipated some sort of cross-examination?

‘Well?’

I pulled myself upright and puffed out my chest. ‘I’m glad you find them so, sir,’ I replied.

‘I was being ironic. I didn’t intend it as a compliment, man!’ He tossed the paper onto the desk. ‘But it doesn’t signify a thing. Forgive me saying so, but your ideas are very out of date. We’ll soon knock them out of you. We do things the modern way here, the scientific way.’

‘I assure you I’m ready to learn,’ I replied and we stood regarding each other a moment, and then, as though suddenly remembering something, he pulled out the watch again.

‘My goodness, is that the time? Come, man, we can’t stand around here gassing all day like a pair of old women; we’re wanted in the treatment area.’

At which he strode past me, opened the door and was through it before I realised what was happening. He moved fast for a small man, bowling along the long corridor like a little terrier in pursuit of a rat.

‘Well, come along, man, get a move on!’ he flung over his shoulder. ‘No time to waste!’

I trotted along after him, finding it difficult to keep up without breaking into a run. ‘May I ask where we’re going, sir?’

He stopped and turned. ‘Didn’t I tell you? No? Hydrotherapy, man, hydrotherapy!’

The word meant nothing to me. All I could think of was hydrophobia, no doubt making an association between the two words because of the place we were in. I followed him through a veritable maze of corridors and passageways, all of them dark and depressing, the walls painted a dull reddish brown, the colour of blood when it has dried on your clothes, and down a flight of stairs that meant we were below ground level, then along a dimly lit passage that finally ended at a metal door upon which he rapped sharply, his fingers ringing against the steel.

‘O’Reilly!’ he yelled. ‘Come along, open up, we don’t have all day.’

As we stood waiting, I was caught sharp by a low moaning sound, like some animal in pain perhaps. It seemed to come from a very long way off.

There was the rasp of a bolt being drawn and we stepped into an immense whiteness that quite dazzled me after the dimness outside. I blinked and saw we were in a huge bathroom. The walls were all white tiles, from which the light from lamps on the walls was reflected and multiplied in strength. Along one wall were a dozen bathtubs, in a row, like beds in a dormitory. A woman in a striped uniform, obviously an attendant, who had opened the door for us and stood holding it, now closed and locked it behind us, using a key on a chain attached to her belt. I realised the moaning noise I had heard was coming from the far end of the room, where two more female attendants, similarly attired to the first, stood over the figure of a woman sitting huddled on the floor between them.

Dr Morgan walked briskly over to the wall at the opposite end of the room, where there was a row of hooks. He removed his jacket and hung it up. ‘Well, come on, man. Take your jacket off,’ he snapped. ‘You don’t want to get it soaked, do you?’

I thought instantly that the armpits were already drenched, but there was nothing for it but to remove it. Luckily Morgan didn’t look at me, although as he turned toward the three figures at the far end of the room, he sniffed the air and pulled a face. I felt my own redden with shame, until I saw he wasn’t even looking at me and probably assumed the stench originated from something in the room.

Rolling up his sleeves, he strode over to the two attendants and their charge, his small feet clicking on the tiled floor. I followed him. The attendants were struggling to make the woman stand up, each tugging at one of her arms. At first I could not see the sitter’s face. Her chin was on her chest and her long dirty blonde hair had tumbled forward, shrouding her features completely.

‘Come on, come on!’ chided Morgan. ‘D’you think I have all day for this? This is Dr Shepherd, my new assistant. He’s here for a demonstration of the hydrotherapy. Get her up now and let’s get started.’

The sound of his voice seemed to have some magical effect upon the crouching creature, who stopped resisting the attendants and allowed herself to be pulled to her feet. She threw back her head, tossing her hair from her face. I saw she was middle-aged, her face well marked from an encounter with the smallpox at some stage of her life. She was a big woman, large boned, and towered over Morgan. Her cheeks were sunken and her eye sockets dark hollow sepulchres. She looked down at Morgan for a moment or so with a suggestion of fear in her expression, but perhaps respect too, and then lifted her eyes to me. It made me uncomfortable, this uninhibited regard. It was not like the look of a human being, but rather some creature, some trapped wild animal. It had in it defiance and the threat of violence and somehow at the same time something that tore at my heart, an appeal for help or mercy perhaps. I well knew what it meant to need both and be denied.

I stared back at her a long moment. I was all atremble and in the end I could not hold her gaze. As I looked away she spoke. ‘You do not appear much of a doctor to me. I shall get no help from you.’ And then, so suddenly she took them by surprise, she wrenched herself free from her keepers and hurled herself at me, her nails reaching for my face. It was fortunate for my already battered looks that O’Reilly, the woman who had let us in and had now come to help us, reacted quickly. Her hands whipped out and grabbed both the woman’s wrists at once in a tight grip. There was a brief struggle but then the other attendants joined in and the patient – for such this wretched being obviously was – was soon under control again. At which point she began once more to wail, making the pitiful sound I’d heard from outside, twisting her body this way and that, tugging her arms, trying to free herself but to no avail, for the two junior attendants who had her each by an arm were themselves well built and evidently strong. Having failed to free herself, the woman began to kick out at them, at which they moved apart, stretching her arms out, one either side of her, so that she was in a crucifixion pose.

‘Stop that now, missy,’ said O’Reilly. Her voice was as cold as the tiles, and it was obvious this flame-haired woman was as hard as nails; the words were spat out in an Irish accent harsh enough to break glass. ‘Stop it or you’ll find yourself getting another slap for your trouble.’

Morgan frowned, then looked at me and raised an eyebrow, a semaphore that I immediately read as meaning that it wasn’t easy to get staff for such employment and that you had to make the best of what was available. He glared at the attendant. ‘None of that, please, O’Reilly. She’s under restraint; no need to threaten the poor soul.’ He turned to me again.

‘Firmness but not cruelty, that’s the motto here.’ Then he told the attendants, ‘Get her in the bath.’

I expected the woman to object to this, but at the mention of the word ‘bath’ her struggling ceased and she allowed herself to be guided over to the nearest one. ‘Raise your arms,’ said O’Reilly, and the woman meekly obeyed. The other women lifted the hem of her dress, a coarse white calico thing, the pattern so faded from frequent washing that it was almost invisible, rolled it upwards and pulled it over her head and arms, with O’Reilly cooing, ‘There’s a good girl now,’ as if she were talking to a newly broken-in horse or a dog she was trying to coax back into its kennel. The woman was left shivering in a thin, knee-length chemise, for the room was not warm, as I could tell from the dank feel of my damp shirt against my back.

O’Reilly put a hand on the woman’s arm, guided her over to the bath and ordered her to get in. The woman looked quizzically at Morgan, who smiled benignly and nodded, and she turned back to the bath, even allowing a certain eagerness into her expression.

‘She is looking forward to a bath,’ Morgan whispered to me out of the corner of his mouth. ‘She hasn’t been here long. She’s never had the treatment before and doesn’t have any inkling of what’s coming.’

I saw that the bath was full of water. The woman lifted a leg over the edge and put her foot into it and instantly let out a gasp and tried to pull it out again, but the attendants immediately seized hold of her and pushed together so that the woman’s foot plunged to the bottom of the bath, whereupon she slipped and as she struggled to regain her balance the attendants lifted the rest of her and thrust her in, virtually face down, with an almighty splash that sent water shooting into the air, with more than a little of it raining down on Morgan and me. The woman’s screams ricocheted off the tiles from wall to wall around the room.

Morgan turned to me with a grin and a lift of the eyebrows, by which I understood him to mean that now I saw the necessity of removing my jacket.

The woman in the bath twisted around to get onto her back and lifted her head spluttering from the water. She tried to get up, but O’Reilly had a hand on her chest holding her down.

‘Get the cover!’ she said to the other women.

They reached under the bath and pulled out a rolled-up length of canvas. The patient tried to scream again but it came out as a wounded-animal whimper that pierced both my ears and my heart.

‘Let me up, for the love of God,’ she begged. ‘The water is freezing. I cannot take a bath in this!’

O’Reilly grabbed the woman’s wrist with her free hand and placed it in a leather strap fixed to the side of the bath. One of the other women let go the canvas and repeated the operation on the other side, so that the woman was now firmly held in a sitting position. Then the attendant returned to the canvas, taking one side of it while her colleague took the other. I saw it had a number of holes ringed with brass along each edge. The woman stopped her screaming and watched wild-eyed as the attendants stretched it over the top of the bath, beginning at the end where her feet were, putting the rings over a series of hooks which I now saw were fixed along the bath under the outside rim. The woman was fighting frantically, trying to get up, but of course she couldn’t because of the wrist restraints, and when this proved to no avail she began thrashing about with her legs, which were under the canvas and merely kicked uselessly against it. O’Reilly stood back now, arms folded, on her face the grim satisfied smile of the practised sadist. In a matter of half a minute the canvas was secured snugly over the top of the bath, the edges so tight it would have been impossible for the woman to get a hand through even if they had not been shackled. At the very top end there was a little half circle cut into the canvas and from this the patient’s head protruded, but the opening was so tight she could not pull her head back down into the water and drown herself.

While this was happening the noise in the room was hellish, the woman’s screams and curses alternating with bouts of calm, when she sobbed and pleaded first with O’Reilly, then the other women and finally with Morgan. ‘Please, doctor, let me out, I beg you. Let me out and I promise I will be a good girl.’

This all came out staccato, for her teeth were chattering, leaving me in no doubt that the water was indeed as freezing as she claimed. When these appeals fell upon deaf ears, she began screaming again and pushing her knees vainly against the canvas, which was so tightly secured it moved scarcely at all.

One of the women went to a cupboard, took out a towel and gave it to Morgan. He dried his face and hands and tossed the towel to me and I did the same. Then he shrugged. ‘We may as well go now, nothing more to be done here.’

He strolled over to where our jackets hung, and began putting his on and I followed suit. I must have looked puzzled and he said something that I could not catch because of the screams of the woman echoing around the room. He rolled his eyes and motioned toward the door. O’Reilly strode over to it and unlocked and opened it and we passed through. The door clanged shut behind us with a finality that made me shiver and I thanked my lucky star that I was not on the wrong side of it, or one like it. The cries of the woman were instantly muffled and Morgan said, ‘She will soon quiet down. The water is icy cold and rapidly calms the hot blood that causes these outbursts.’

‘She seemed calm enough before she was put into the bath,’ I said, forgetting myself and then realising I had perhaps sounded a note of protest.

He began walking swiftly, so that again I had trouble keeping up. ‘Momentarily, yes, but she has been given to fits of violence, such as you witnessed a little of, ever since she arrived here a week ago. The hydrotherapy has a wonderfully quiescent effect. Another three hours in there and—’

‘Three hours!’

I could not help myself. It was unthinkable to me that you could put someone in freezing cold water in the fall and leave them like that for three hours.

He stopped and looked at me, taken aback by my tone. Before I had time to think about it, I raised my hand to cover the bruise and was suddenly conscious of how I must appear to him, with my too-small jacket and my bashed-about face.

‘I know it may seem harsh to the untrained spectator,’ he said, ‘but believe me it works ninety-nine per cent of the time. She’ll be as meek as a newborn lamb after this, I assure you. And I’d go so far as to wager that after another three or four such treatments there will be no more violent fits. We will have her under control.’

‘You mean she will be cured?’

He pursed his lips and moved his head from side to side, weighing up his reply. ‘Well, not exactly. Not as you probably mean.’ He began walking again, but this time slowly, as though the need to choose his words carefully forced him to slacken his pace. ‘We must be sure of our terms here, Shepherd. Now, she will not be cured in the sense that she can be released and live a normal and productive life. Immersing her in cold water will not repair a damaged brain. So from that point of view, no, not cured. But think of what madness involves. Who is most inconvenienced by mental affliction?’

‘Why, the sufferer, of course.’

‘Not so, or rather not necessarily so. Often the patient is in a world of her own, living a fantasy existence, in a complete fog, and does not even know where she is or that the mental confusion she feels is not the normal state of all mankind. No, in many – I would even go so far as to say most – cases, it is the people around her who endure far more hardship. The family whose life is disrupted. The children who are forced to put up with bouts of abuse and violence. The poor husband whose wife tries to hurt him or turns the home into a place of fear. The parents who are too old to restrain a daughter undergoing a violent episode. And, not least, us, the doctors and attendants whose duty it is to care for these unfortunate beings. So not a cure for the patient, but one for everyone else, whose lives are made better because the illness is being managed.’

We continued walking in silence for a minute or so.

‘So the patient can never resume her place in society, then?’ I asked at last.

‘I would not say never, no. After a period of restraint, of being shown again and again that making a nuisance or herself will gain her nothing, a patient will often become subdued. It is the same process as training an animal. The fear of more treatment leads to compliance. In the best cases it becomes the normal habit. Oh, I know some may not like to admit it, but it’s a tried and tested regimen. It worked for King George III of England, you know. He went mad, but after a course of such treatment the merest hint of restraint would cool his intemperance and he was able to take up the reins of government again for another twenty years.’

2 (#ulink_7274a858-e218-5805-86fc-9bce4a7dc74c)

After our visit to the hydrotherapy room, Morgan took me on a brief tour of the institution. We began on the second floor, where the dormitories were arranged along a long corridor that must have run a good deal of the length of the building. Most of the women slept in large rooms accommodating twenty or so beds, although some were in smaller rooms, and a few were in isolation.

‘It may be that they are violent or that there is something about them, some habit or tic that is a nuisance to others that makes them a victim of violence, or simply that they continually make a racket and keep everyone else awake,’ Morgan explained. ‘We try to keep things as peaceful as possible.’

Each sleeping area had a room nearby where two attendants alternately slept and kept watch. ‘Is this to prevent the patients escaping?’ I asked.

‘Escaping? Escaping?’ He looked askance at me. ‘Good God, man, they cannot escape, because in order to do so they would first have to be prisoners. They are not; they are patients. They do not escape; they abscond. Or would do if we were to let them. Anyway, the sleeping quarters are locked at night so they cannot wander.’

I surveyed the length of the corridor and the many doors. ‘What about the risk of fire? Surely if one broke out, there would not be time to unlock all these doors?’

He sighed. ‘You may well be right. I have my doubts about some of the women we are forced to employ and fear that in such a case they would think only of saving themselves rather than chance their own lives getting the patients out.’

‘I’ve seen a system where the doors in a corridor are linked and locked by a device at the end of the row that secures or releases them all at once.’

He stopped and stared at me. ‘I know of only one institution that has such a system. Sing Sing prison. How came you to see it?’

I could only hope he didn’t notice my momentary hesitation before replying. ‘I didn’t mean I’d actually seen it, sir. I meant that I had seen there is such a system. I think I read about it in the Clarion or some other newspaper.’

He resumed walking. ‘I’m sure we cannot afford such luxuries. The state will fund these things for lawbreakers, but not, alas, for lunatics.’

I could not help clenching my fists at the idea that prevention from being burned to death in a locked room should be considered a luxury, but said nothing. I was not here, after all, to take up the cause of the lunatics.

On the ground floor we visited a long bleak room with bare wooden benches around the walls, bolted to them, all occupied by inmates, and in the centre a table covered by a shining white cloth, around which sat half a dozen attendants. The entire room was as spotless as the tablecloth and I thought what a good job the attendants must do to keep it so clean. I would later mock my own stupidity for this assumption. At either end of the table were two potbelly stoves, whose heat I could only feel from a few feet away when we approached them, but even if my own experience hadn’t told me they were inadequate to the task of heating such a large room, I would have known because the women on the benches were shivering and hugging themselves for warmth. The backs of the benches were perfectly straight and you could tell they were uncomfortable from the way the inmates were forced to sit upright upon them, the seats being so narrow the sitter would simply slide off if she slouched. Each bench looked as if it would accommodate five people, which I could tell from the fact that every one had six women sitting on it and looked unpleasantly crowded. These inmates were all clad in the same coarse, drab calico garment I had seen on the woman in the hydrotherapy room. On one side of the room were three barred windows set at more than five feet from the ground, so that even standing, let alone sitting, it was impossible for any but an exceptionally tall woman to see out of them.

When I mentioned this to Morgan, thinking, but not saying, that it was a poor piece of design, he said, ‘That’s the idea. We do not want them looking out – it would be a distraction.’

I had to bite my tongue not to ask distraction from what, since the women had absolutely nothing to occupy them. There was no sound from any of them and they all seemed subdued, staring blankly into space, or down at the floor or even sitting with their eyes closed and possibly dozing, until they became aware of us, whereupon I sensed a ripple of excitement pass around the room.

A woman stood up and approached Morgan. She stretched out a hand and tugged his sleeve. ‘Doctor, doctor, have you come to sign my release?’ she said. She was old, perhaps sixty or so, with a bent back and a brown wizened walnut of a face.

Carefully, he lifted her hand from his arm as if it had been some delicate inanimate object and let it drop gently by her side. ‘Not today, Sarah, not today,’ he told her. ‘Now be a good girl and sit down, for you know we have to see you can behave properly before there can be any talk of release.’

I was impressed he knew her by name – he’d told me there were some four hundred patients in the hospital – which made him smile. ‘She’s been here thirty years, since long before my time. She asks me the same thing on every occasion she sets eyes on me; she does not realise she will never go home.’

While this had been going on, other patients had taken their lead from Sarah and risen from their seats and a great hubbub of chatter had sprung up. In response to this disturbance the attendants rose from the table and busied themselves taking hold of those who were walking about and leading them back to the benches and where necessary pushing them down onto them. ‘Now behave!’ I heard one attendant snap at a young woman. ‘Or you’ll be for it later.’ Instantly the woman turned pale and meekly went back to her place.

Eventually all the patients were seated again and after a few more stern words from the attendants, the chatter died down and silence reigned once more. Some still looked at us, with what seemed like great interest, but most resumed their earlier pose, and simply sat and stared empty-eyed straight ahead, not even making eye contact with the women sitting opposite them on the other side of the room.

‘What are they doing here?’ I whispered to Morgan.

‘Doing? Doing? Why, man, you see for yourself, they are not doing anything. This is the day room, where they spend much of the day. They will sit like this until it is time for their evening meal.’

‘When do they have that?’

‘At six o’clock.’

It was presently only four o’clock. I could not help thinking that if I were made to sit in total silence with nothing at all to occupy me, even if I were not off my head to begin with, I soon would be.

Morgan looked at me angrily, and I wondered for a moment whether I’d actually spoken my thoughts aloud, but being sure I hadn’t, I saw I had irritated him by the tone of my questions. He took my queries as criticism of the regime, which, I began to see, they were, since I was so appalled by what I was seeing that I could not prevent a certain disbelief creeping into my tone.

‘It is, as I said,’ he paused to let go a sigh of exasperation, ‘a question of management. If they were all doing something, they would be more difficult to manage. Any activity would have to involve something to do it with. If you allowed them books, for example, some of them would damage the books, or they would throw them at the attendants, or use them as weapons against their neighbours. And even if they simply read them it would not be good, for it would give them ideas. They have too many ideas already. It would be the same with sewing or knitting. Can you imagine the possible consequences of handing them needles? So removing potentially dangerous objects and maintaining an air of calm is essential for control. But also it is therapeutic. They acquire through practice the ability to sit and do nothing. It teaches them to be calm. If they can do this, then both their lives and ours are made easier.’

After this he took me outside via a rear entrance to show me the grounds. There were extensive lawns and an ornamental pond and beyond this some woodland. I felt a great relief to be out in the open air. I looked back at the hospital. It was a forbidding sight and I could not help thinking how daunting the first approach to it must be for a new patient. The style was gothic, with a fake medieval tower at one end and a round turret at the other. Much of it was strangled by ivy. The windows were small, which accounted for the gloom within, many of them merely narrow openings to imitate the arrow slits of an ancient castle.

Once again Morgan must have read my thoughts. ‘Dismal-looking edifice, isn’t it?’

I turned away from it. ‘I fear no one could say otherwise. It looks as if it ought to be haunted.’

He began to walk away and I heard him mutter something that sounded like, ‘Oh it is, my boy, believe me, it is.’ I had the sense that he was talking to himself and did not think I could hear him.

I caught up with him just as we came upon a group of lunatics out for their daily walk. Still clad in their same worn calico dresses, each woman now had a woollen shawl and, bizarrely, a straw hat, such as you might wear on a day out on Coney Island, making the overall impression strangely comic. The women were lined up in twos, guarded by attendants.

As they passed us, a shiver of horror crept through me. My gaze was met with vacant eyes and inexpressive faces, while many of them jabbered away, seemingly holding conversations with themselves, or sometimes leaning toward their partners and talking animatedly, although in most cases the other woman appeared not to be listening, either staring mutely ahead or muttering away herself, lost in a conversation of her own. I saw too that these women were under restraint. Wide leather belts were locked around their waists and attached to a long cable rope, so that they were all linked to one another, a sight that reminded me of old illustrations I had seen of slaves being led from their African villages to the slavers’ ships. I did a rough count and estimated there must have been around twenty women roped together in this fashion.

We stood aside to let them pass and I could see many of them had dirty noses, unkempt hair and grimy skin. My own nostrils attested that they were not clean, whereas I hadn’t noticed any unpleasant smells amongst the other women in the day room and was surprised that there should be any now we were in the fresh air.

‘Who are these women?’ I asked Morgan.

‘They’re the most violent on the island,’ he replied. ‘They are kept on the third floor, separate from the rest. They are all extremely disturbed and their presence would not be compatible with the treatment of the others.’

As if to verify this, one of them began to yell, which sparked off a reaction in another, who commenced to sing, in a strangely beautiful and haunting voice, the old song ‘Barbara Allen’, and for a moment it felt as if the sadness of the song was a reflection of her state, but then others broke out in a discordant caterwauling, raucous stuff such as you hear in low taverns, and one woman added to the cacophony by mumbling prayers, while others stuck to simple cursing, casting oaths defiantly into the air seemingly at nothing or no one in particular, but to the world in general and what it had done to them.

The women were forced to keep to the footpaths and I thought how they must have longed to kick off their shoes and run barefoot across the soft, elegantly coiffed grass. Every so often one of them would bend and pick up something, a leaf or nut or fallen twig, but immediately an attendant would be upon her and force her to discard it.

‘They are not allowed possessions,’ Morgan observed to me.

Possessions! What kind of hell was this where a fallen leaf was counted a possession? I could not help but be reminded of Lear, in which I had once played Edmund – who else? – and the old king’s speech: ‘Oh, reason not the need, our basest beggars are in the poorest thing superfluous.’

Following in the wake of this miserable spectacle of humanity, we passed a small pavilion, no doubt a vestige from the days when the asylum had been a private residence. On the wall was painted in elegant script ‘While I live, I hope.’ I shook my head at the irony of this; you only had to look at these poor women shuffling along to see there was no truth in it.

We wandered the grounds for the best part of an hour, during which I had several uncomfortable moments, as every now and then Morgan attempted to quiz me on my ideas for the treatment of lunatics, while at the same time ridiculing them without managing to convey any clue as to what these ideas actually were. I began to feel quite aggrieved that he should patronise me so and frustrated that I could not produce any counter-argument, and sensed myself losing control, which of course would have ruined everything. I held my tongue only with the greatest difficulty.

Morgan pulled out his watch. ‘Dinner in six minutes. You may as well observe the dining hall.’

Back inside the hospital we looked on as the more violent inmates, still in twos, were marched through a doorway in shambling parody of a military manoeuvre. They were taken off to a separate dining room, Morgan told me, for they needed careful supervision while they ate. After they had gone, I followed him into the long, narrow dining hall where the rest of the patients were standing, behind backless benches on either side of plain deal tables that ran almost the entire length of the hall’s centre. At a word from one of the attendants the inmates began to scramble over the benches and take their places upon them in such a disorderly fashion I couldn’t help thinking of pigs at the trough.

All along the tables were bowls filled with a dirty-looking liquid that Morgan assured me was tea. By each was a piece of bread, cut thick and buttered. Beside that was a small saucer that, as I peered more closely, proved to contain prunes. I counted five on each, no more no less. As I watched, one woman grabbed several saucers, one after the other, and emptied the prunes into her own. Then, holding tight to her own bowl of tea, she stole that of the woman next to her and gulped it down.

Morgan watched and, when I glanced at him, lifted his eyebrow and said, ‘Survival of the fittest,’ and smiled.

Looking around the tables, I saw women snatching other people’s bread and others left with nothing at all. All this Morgan viewed with such complete indifference that I began to despair of humanity, until I noticed one inmate, a young woman, not much more than a girl really, with long dark hair that fell down over her face, half veiling it, tear her own slice of bread in two and pass one portion to the woman next to her, who had been robbed of her own and who accepted it eagerly, showing her gratitude with a smile, the first I had seen in this place. At this moment, as if feeling the weight of my eyes upon her, the girl who had given away her own bread lifted her head and stared straight at me with a look that chilled me to the bone. It had a knowingness in it, as if she saw right through me and recognised what I was and observed something in me that enabled her to claim kinship. I was only able to hold her gaze for a short time before I had to look away. A minute or so later, I glanced back at her and, finding her eyes still fastened upon me, had to turn away and walk to the other end of the room.

While all this scramble for food was going on, attendants prowled up and down behind the women, not bothering to stop the petty larcenies, but tossing an extra slice of bread here and there when they saw someone going without.

When the bread and prunes had been consumed, which in truth didn’t take long, for there was not much of it and the women were obviously ravenous, the attendants fetched large metal cans from which they dispensed onto each of the women’s now empty plates a small lump of grey meat, fatty and unappetising, and a single boiled potato. You’d have thought a dog would have baulked at it, and indeed I don’t think I ever saw a dog so poorly fed, but the women fell upon it as if it was the most sumptuous feast. A few, I noticed, grimaced as they bit into the meat, showing it to be as rancid as it looked, but managed to swallow it nonetheless. Everyone else devoured it as fast as they could chew it – and it was evidently so tough, this was no easy thing – and, when it and the potato were done, looked balefully at their plates as though they could not believe the meagre offering was already gone.

Afterwards Morgan and I had our dinner in the doctors’ dining room. Although the dining table would have accommodated six people, there were only the two of us. I asked how many other physicians there were, at which Morgan shrugged. ‘We do not have unlimited resources, you know. The state does not set great store on treating the mentally ill. We cannot afford to employ more staff or anyone more experienced than you. Which is fortunate for you. Normally someone just starting out upon a career as a psychiatric doctor might wait years for an opportunity such as you have here.’

‘Indeed, I am very grateful for it, sir,’ I said, deciding some humble pie as an appetiser would not go amiss.

‘Especially with your old-fashioned ideas,’ added Morgan.

Fortunately I was not called upon to explain them as just then our food was brought in, which quite captured Morgan’s attention. There was a decent grilled sole to start, followed by a very acceptable steak and a variety of cooked vegetables. It was more than passable. I’d eaten worse in many hotels and it was certainly much better than the fare I’d had recently. The bottle of wine we shared was a luxury I hadn’t tasted for a considerable time.

Afterwards there was an excellent steamed treacle pudding, followed by a selection of cheeses. When we had finished and rose from the table I took advantage of Morgan consulting his watch, which he seemed to do every few minutes, to slip the sharp cheese knife up my sleeve.

‘Well, then,’ said Morgan, ‘you will no doubt be tired after all your travelling, not to mention your encounter with public transport, and I have some correspondence to attend to, so I will say goodnight.’ To my horror, he stretched out his hand for me to shake, which of course I could not do because I had the knife up my right sleeve with its handle cupped in the palm of my hand. There was an awkward moment when I did not respond and his hand was suspended in a kind of limbo between us.

He cleared his throat and, as smoothly as a trained actor overcoming a colleague’s missing of a cue, turned the thwarted handshake into a gesture toward the door, as though that had been what he had intended to do all along, and we proceeded to it, where he paused and said, ‘Oh, there’s a small library for the staff, over near my office, if you should want to read before retiring. It contains mainly medical books.’ Here he lowered his head and shot me a lightly mocking look. ‘Some of them may inform you about, shall we say, modern treatments, but there are also some novels and books of poetry, should you simply want relaxation.’

I thanked him and said I would walk back in that direction with him to find something to look at before I turned in. Letting him go ahead, I slipped the knife into my jacket pocket.

We made our way along the passage that led to the main entrance in silence. The place had settled down for the night and the gas lamps in the corridor were turned low. From somewhere far distant above us came a soft moan that could have been the sorrowful cries of patients or perhaps the lowing of the wind. I shivered to think of those lost souls, for whatever reason not at rest, who even now would be wandering the night, keening at their fate.

At his office door Morgan pointed me along a passage that ran at right angles to the one running the length of the house that we’d just come along. ‘The library is at the end of this passage, last door on the left. You’ll need a light.’

The corridor was completely dark. He went into his office and emerged with a lit candle on a brass holder. He handed it to me, together with some matches. ‘Not all the property is fitted with gas.’

We said goodnight and this time I proffered my hand in order to allay any suspicions he might have harboured about my reluctance to shake with him earlier. Once again his firm grip on my bruised bones invoked an involuntary grimace that I did my best to disguise as a smile. He went into his office and shut the door behind him, cutting off the light from within and plunging me into a twilight world.

Shadows brought to life by my feeble candle flickered on the walls and I could not see very far along the passage ahead of me. ‘Darkness be my friend,’ I said, although it didn’t fit, because for once I didn’t need its cloak to hide me, but saying it somehow made me feel less afraid, for I confess I was, although I could not have told you exactly why. There was something so eerie about the place, what with that constant distant moan, the misery of so many forlorn ghosts, that a depression settled upon me and began to seep into my very core. A book would do me good, to divert my thoughts to something sunnier, and I set off along the dim passage, although not with any great confidence. I could not help myself from creeping, treading softly, for the sound of my own footsteps bothered me as though they might be those of another, or perhaps for fear the noise might awaken some sleeping enemy as yet still hidden from me. Eventually I reached the end of the corridor and found the door to the library. It opened with a creak like a sound effect from one of those old melodramas in which it has too often been my misfortune to be involved.

It wasn’t a very big room, only the size of a modest drawing room, which made me think reading and literature had not been a priority for whoever had had the place built as a private residence. All four walls were lined floor to ceiling with shelves of books. I walked around the room, casting the light of my candle over the spines. On first inspection their bindings all appeared old, foxed and mildewed, the gilt titles faded and their shine dulled. The place had the graveyard scent of mouldy neglect and I supposed the room and its contents had fallen into disuse once the place was turned into a hospital. Who here would want to read books now? The patients weren’t allowed; Morgan had told me as much. The attendants had struck me as ignorant and uneducated, and that left only the doctors, and evidently not many of them had been of a literary turn of mind, because the dust on the shelves showed the volumes upon them had rested undisturbed for some considerable time. In one small section, though, I came upon books that were relatively new, the wood of the shelves cleaner, showing they had been taken out and put back. A closer look revealed they were all upon medical subjects, mostly to do with mental illness. I read their titles, which were so mystifying to me they might as well have been in Japanese, and I could not decide upon one to favour above the others and consequently, in the end, didn’t examine any of them more closely. I was tired and not in the mood and, even though it would have been sensible to begin at once my education in my new profession, I understood myself sufficiently well to know I would not read anything about it tonight.

I went to the next section, which was comprised of the ubiquitous ancient worn stock, and here struck gold in a large, shabby volume and had no need to look further. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare in a handsome though battered edition. I set my candle down upon a small table and took the book from the shelf. It fell open at the Scottish Play. I shivered. Was this a bad omen? It was certainly not what I would have chosen to read in such a setting and I was about to turn to something lighter, one of the comedies, when at that very moment my candle flickered. I felt the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end as from behind me came the plaintive creak of the door. There was the patter of bare feet over floorboards and I swivelled round in time to see a wisp of white, the hem of a woman’s dress or nightgown, whisk around the edge of the door, its wearer seemingly fleeing after finding me there, and pulling the door shut behind her with such a slam the draught from it killed my candle dead.

It was pitch dark. I fumbled about, feeling for the candle, but succeeded only in barking my shin against some piece of furniture, drawing from me an involuntary oath. I shuddered at the sound of my own voice, as though if I only managed to keep quiet the intruder would ignore me, which, of course, was plain stupid of me. I remonstrated with myself for my cowardliness, asking myself why I, who had lately been in a far worse situation, was so fearful. I could only put it down to my being here, in this madhouse, where I should not have been, although I had every right to be here, so far as anyone else knew.

I felt about with my hands stretched out in front of me like a blind man, trying to remember exactly where I had set down the candleholder, but in my panic could remember nothing of the room. I told myself I must think clearly and sucked in a couple of deep breaths, got myself calm again and eventually laid my hand on the candleholder. I found the box of matches Morgan had placed on it and fumbled one out and struck it, the noise like an explosion in the dead silence of the night. I had great difficulty in applying the flame to the wick, my hand was shaking so. The match went out and I struggled to light another, the light flickering wildly as my fingers trembled. I steadied myself and at last the thing was lit. As visibility returned and the edges of the room fell into place, so my terror abated. I felt as if I had seen a ghost, and indeed it was not too fanciful to believe that I had. That fleeting suggestion of white dress, the patter of feet – it was all the stuff of tales of hauntings.

It was with some trepidation that I eased open the door, in dread of its rusty creaking. All this achieved was to protract the noise of its unoiled hinges, which took on the sound of a small animal, or some ghostly child perhaps, being tortured. As soon as there was enough of an opening, I insinuated myself around the edge of the door and shuffled my way along the passage outside, fearing that at any moment the spectre would come rushing at me and – and – and what? That’s the thing about terror: it’s the not knowing that gets to you and what your mind makes up instead. I stood still a moment, took another deep breath and rationalised what had happened. I had seen a hint of female garment. It was a woman and I was a strong fit man; what did I have to be afraid of? But then I began to think what woman it might be. The most likely was one of the attendants, of course, because by now the inmates were all safely locked in their dormitories (safely as long as there wasn’t a fire!). But what if one should have escaped somehow? What then? What if she were violent? I shuddered at the thought of some madwoman launching herself out of the shadows at me and found myself twitching with every flicker of the candle flame, at every dancing shadow on the walls.

It seemed an age before I achieved the end of the passage. The gas lamps in the main corridor had now been extinguished and there was no light showing under Morgan’s door, so I guessed he must have retired for the night. The silence overwhelmed me because every instant I expected it to be broken by that other presence I had glimpsed. I made my way up the main staircase, treading as softly as I could, for it was old and as creaky as the library door and apt to groan a protest at every step. On the second floor everything was unfamiliar in the weak candlelight and I made several false turns before I found the right passageway and at long last made my way toward the safety of my room.

3 (#ulink_841cb80b-7307-594a-9cec-587ed364e26a)

With a sigh of relief I closed the door behind me and leaned my back against it, sucking in deep gulps of air because I had, without realising it until now, been holding my breath for so long. I put a hand to my face and found my forehead was clammy. The bruise there seemed to be thumping away in time with my overworked heart. Several minutes passed before I was composed enough to put the candle down upon the writing desk, although my hands were still shaking. It took another few minutes before I felt confident enough of not injuring myself to take the cheese knife I had stolen from my pocket and set about the valise locks. The knife was very thin and the curl at the top of it made it ideal for the task, and the case and its locks were cheap. After no more than a couple of minutes I had triggered the springs of both locks and snapped them open. I took another deep breath to steel myself to lift the lid. What if the contents weren’t sufficient for my basic needs? What if there were no spare shirts or linen? It was perfectly possible. They might have been in some steamer trunk in the baggage car for all I knew. I flung open the lid, and saw to my relief a pile of neatly folded shirts, underwear, socks, a spare pair of pants, a washbag containing toothbrush and powder, a hairbrush, a bottle of hair oil, a razor and so on. I lifted them out and found underneath a book, the boards well worn from use, the spine slightly torn. As I picked it up I realised I had put down the Shakespeare in the darkness in the library to look for my candle and in my terror never thought to take it up again, and so felt a little surge of pleasure that at least I had here a book to divert me from my gloomy imaginings. I took it up from the valise and read the title from the spine. Moral Treatment by Reverend Andrew Abrahams.

I tossed it onto the writing desk in disgust. Obviously some uplifting Christian work. Just my luck! I’d rather have had the Bible itself; at least the language is memorable and there’s a rip-roaring story or two, not to mention a fair bit of adultery. But God save me from the sanctimonious religious writings of the present time, when men ought to know better. Still, at least it told me something about the sort of pious fool I had become.

Having nothing to entertain me, I got on with the necessary business of hanging up my clothes in the closet and laying out my toiletries on the chest of drawers. I put the valise under the bed, undressed and put on my nightshirt, which was just the kind of scratchy garment you’d expect from some Holy Roller, like sleeping in sackcloth, although after a short time it ceased to matter, for soon after my head hit the pillow, I was lost to the world.

I did not pass a peaceful night but was troubled by a succession of dark dreams. In most of them I was wandering along dimly lit corridors, haunted by shadowy corners from which, with no warning, and screams that froze the blood solid in my veins, women would fling themselves upon me, their faces hideously deformed, eyes black with madness, lips red as arterial blood, teeth bared like wolf fangs and dripping with hunger, their fingertips ending in long talons which raked my face, tearing at my eyes. I finally awoke from one of these nightmares to the sound of birds singing and light pouring in around the edges of the blind at the window, and although I normally have no time for Him, thanked God that at last day had dawned.

My nightshirt and the sheets were soaked with sweat. I wondered that I should have been so frightened to cause this and then worried that it might not be anything to do with my dreams but rather because I had suffered some serious injury in the accident, that perhaps the blow to my head had caused a fever of the brain.

I could hear footsteps in the corridor outside, doors opening and closing, the hollow echo of distant shouts, all the noises of a large institution rousing itself for another day, dreadfully familiar to me from the past few months but somehow different too. I threw back the blankets and got out of bed. There was no heating and it was cold, though not so cold as where I had just come from. I took off the nightshirt, found a cloth and a bar of soap in the washbag, poured myself a bowl of water and, after recovering from the shock of its bracing temperature, gave myself a thorough scrubbing. I examined the bruise on my forehead in the mirror and was glad to see it appeared less livid. This minor improvement was enough to give me a little surge of optimism and kindle the belief I might survive here for a while, that everything would be OK. I dressed in clean linen, shirt and necktie and pulled on the spare pare of pants. I sniffed the armpits of the jacket I’d had on, the only one I possessed, and recoiled at the stench of stale sweat. I opened the bottle of hair oil, which proved to be scented. There was no way I was letting the stuff anywhere near my head, but I shook a little into the armpit linings of the jacket and rubbed it in. The effect might make me stink like a French pimp but on the other hand it was to be preferred to yesterday’s sweat.

I had no timepiece. The one I’d found in the jacket had been smashed in the accident and I’d thrown it away. So I had no idea of the hour, but it sounded sufficiently busy outside to think it was time I should be abroad.

I made my way downstairs and, coming across the maid who had first shown me to my room, I saw now that she was pretty and could not help noticing how long and slender was her neck, elegant as a swan’s, surprising on so coarse a person. I asked where I might find Dr Morgan and she directed me to the staff dining room.

‘Ah, Shepherd,’ he said when I walked in, and I nodded self-consciously. ‘Come and get some fuel inside you, we have another busy day.’

Breakfast proved a sumptuous meal, with devilled kidneys, grits, eggs, bacon, toast and preserves and a great pot of freshly brewed coffee, of which Morgan consumed a prodigious quantity, causing the pupils of his gimlet eyes to expand into an almost fanatical stare as he grew more and more animated.

Although I had put away a good amount of food the night before, I found I was still famished, which I blamed on my many months of deprivation, and busied myself getting as much down me as I could. The uncertainty of my lifelong career and especially my late unfortunate experiences had taught me never to presume too much where your next meal might be coming from but at every opportunity to fill your stomach against the evil day that was sure to be just around the corner. At the same time I could not help thinking of the miserable meal the poor wretches who were confined here had had last night and to feel more than a mite of sympathy for them. So preoccupied did I become by this that my attention must have wandered from what Morgan was saying, although he hadn’t noticed and, carried away on a tide of caffeine, was rabbiting on at a furious pace, until suddenly something in his gabble flicked a switch within my brain.

‘… the most tried and tested of modern treatments, the restraining chair, used so successfully on George III, only this is a much modified, up-to-date model, designed by myself. You’ll soon forget your silly notions about Moral Treatment when you see the practical application of today’s methods. It’s no use harking back to the past …’

I sat upright. ‘Sorry,’ I said, ‘I didn’t quiet catch that. What did you just say?’

‘I said it was no use harking back to the past.’

‘No, before that.’

‘I was telling you you will soon abandon those silly outmoded notions you have of Moral Treatment.’ He looked at me. ‘What is it, man?’

‘Oh, nothing,’ I said, waving a piece of toast in what I hoped was a casual manner. ‘I just misheard you the first time, that’s all.’

‘Well, come on, aren’t you going to argue with me? Put up your case, there’s a good fellow, and then I can knock it down.’

I shook my head. ‘No, no, not now, not at breakfast,’ I mumbled. ‘I can’t think clearly when I’m not properly awake.’

So I was not such a pious idiot after all! The book in my room was to do with the treatment of lunatics and not a religious tract. If only I had taken the trouble to open it last night! As it was, I would have to dodge any further discourse on the subject with Morgan until I could slip away upstairs and take a look at the book. I could not hope to keep avoiding discussion about my beliefs; it was imperative I find out as soon as possible just exactly what they were.

Breakfast was accomplished on my part at an indigestion-inducing rate because Morgan had a good start on me with it and when he was finished kept consulting his watch and tut-tutting impatiently as a not very subtle signal to me to hurry up. I did not mean to leave the room without a full stomach, however, and stuffed the rest of the food on my plate into my mouth, bolting it down as fast as I could, with hardly any recourse to the action of my teeth or troubling to taste it.

I had scarcely swallowed the last morsel of bacon before Morgan was on his feet, pocket watch out and heading for the door. I scraped back my chair, mopped my mouth with my napkin, took a last regretful swig of coffee and trotted after him. As I caught up, Morgan stopped abruptly, so I almost cannoned into his back. He lifted his head and sniffed the air like a hunting dog. ‘Can you smell anything peculiar?’ he said.

I took a sniff myself and shook my head. ‘No, sir.’

He shrugged. ‘Hmm, funny that, could have sworn I smelt flowers. Rose petals if I’m not mistaken.’ He peered at me suspiciously for a moment, which I returned with a blank face. He shrugged again, turned and walked on briskly. It seemed I had overdone the pomade in my jacket. I could not help wondering what my new boss was thinking of me now. I hurried after him once more, trying my best to hold in check what threatened to be a mighty belch.

The morning consisted of examining various ‘difficult’ patients. In one room we found O’Reilly and another attendant standing beside a thin, pale, fair-haired woman sitting on a stool. No sooner were we inside than Morgan’s nose was raised and twitching again, and, even with the protection of my perfumed armpits, I could smell something unpleasant.

Morgan took a clipboard from O’Reilly and read through the papers on it swiftly. He handed it back to her without comment or even looking at her and advanced toward the woman. ‘Now, now, Lizzie, what’s this I hear? You’ve been playing with your excrement again.’

She looked up and gave him a wan smile. ‘I have indeed, sir,’ she said, ‘and I enjoyed myself immensely.’

Morgan turned to O’Reilly. ‘Completely unrepentant!’

‘Yes, sir,’ she replied. ‘Bold as brass. It’s been the devil of a job to get her clean again. We’ve had no cooperation from her at all.’

He sighed and looked back at the woman with the assumed sadness adults use when dealing with misbehaving small children. ‘Very well, then, nothing for it but the chair. Longer this time. I did think we would not need it again with her, but I see now that last time we tried to rush things and did not give the treatment sufficient time to do its work.’

At the mention of the word ‘chair’ the patient’s face blanched, something you would not have thought possible because it had been so pale already. ‘Oh, no, sir, not the chair,’ she protested, as the attendants took hold of her arms and pulled her from her seat. The woman resisted, trying to tug her arms free, but the attendants were muscular and strong and obviously better fed than she and they wrestled her toward a side door. Morgan strode swiftly around the group and opened it. At this the patient suddenly went limp and became a dead weight, forcing the attendants to drag her along, her legs trailing behind her, and all the while she was shouting and screaming exactly like a woman who has just realised she is about to be murdered.

Morgan went after them into the adjoining room, indicating with an impatient wave of his hand that I should follow. The room was bare save for a heavy upright wooden chair, which was bolted to the floorboards. The arms and legs of the chair were fitted with leather straps, with another stretched across the front of its high back. At the sight of the chair the woman came to life again and began fighting once more. The attendants hauled her into it, manhandling her calmly in the face of fierce opposition on her part, got her hands strapped to the arms and then proceeded to strap her ankles to the legs in spite of her kicking feet. Finally, they placed the strap attached to the chair back around her throat. A strap like that could strangle a woman, I thought.

All the time the woman was screaming and resisting with what little power she had. I really don’t enjoy seeing a woman struggle. I have no liking for torture.

‘If you leave me here, I will piss myself, I swear I will,’ the woman shouted.

O’Reilly turned to Morgan, and raised an eyebrow. ‘Gag?’

He nodded and she produced a piece of rolled cloth from her pocket, evidently made for the purpose, at the sight of which the woman stopped screaming and closed her mouth firmly, turning the lips inwards so you could not see them. Her panic showed in her eyes, which swivelled this way and that, desperately searching for some means of escape, like a cornered rat. The junior attendant went behind her, seized her head in an arm hold to prevent her shaking it around and with her free hand pinched the poor woman’s nose tightly. Thus it was only a matter of time before she was forced to open her mouth to breathe, whereupon O’Reilly shoved the gag between her teeth while the other proceeded to tie it behind the woman’s head.

After this, unable to move much at all, the poor wretch in the chair gave up the fight and her body slumped. No dignity remained to her and, lacking any other means of defiance, she carried out her threat and opened her bladder and urine began to drip from the chair and pool upon the floor below.

I watched in horror, appalled at what I was seeing, but Morgan seemed completely unmoved by the woman’s plight, as did O’Reilly and the other attendant. All three were so extremely matter-of-fact about the whole affair, it was obvious it must be a daily occurrence in their lives. Morgan strolled back into the other room and retrieved the clipboard from where O’Reilly had put it down. Returning to us, he studied it, lifting the top sheet of paper, then the one underneath.

‘I see we gave her only three hours last time.’

‘That’s right, sir,’ said O’Reilly.

‘I think then that this time we’ll try six. That should do the trick.’

The eyes of the woman in the chair widened in terror at these words. It was her only method of expression. Morgan walked over to her and said, in a kindly tone, ‘Now then, Lizzie, you may as well settle down because you are going to be here for quite the long haul. During that time I want you to consider the foolish behaviour that has led you to this situation and to consider modifying it so that you never have to find yourself here again. I hope that after this there will be no more soiling of yourself.’

He stood and smiled benignly, with the air of one who is conferring the greatest of favours, and as if waiting for some kind of response, though of course there was no way the unfortunate woman could give any, except to blink. Then, in that abrupt way he had of doing things, he turned to O’Reilly, thrust the clipboard into her hands and without another word marched out of the room. I caught up with him in the corridor.

‘Six hours to be so restrained seems a terrible long time,’ I ventured.

‘You think so?’ He stopped and looked at me with surprise. ‘Why, not at all, man, not at all. Ten or twelve is sometimes necessary.’

‘It seems so – so, well, harsh. Is there truly no other way?’

He looked exasperated. ‘There we go again, with your old-style ideas. Ideas I may say that were formulated by a gaggle of well-meaning but ill-informed, completely unqualified Quakers, rather than doctors, and that have no basis in science. Come, man, let’s have it out now, why don’t we? I can’t have you working here if you mean to challenge everything we do.’

I had no notion of how I had pushed him into this. His rage seemed out of all proportion to the objection I had made. His face was red with indignation, his cheeks puffed out, like an angry bullfrog. I thought his head was going to explode. I did not know what to say. It was not like drying up on stage, for I had no script. Indeed, I was not at all sure what my role here was. I tried to improvise but all that came out was a stammer. His features relaxed and his old calm smugness seemed to flow back. ‘Well? Cat got your tongue?’

‘I will gladly fight my corner, sir, only I would like the opportunity to reflect upon what I have seen here, if I may, and to formulate my reply carefully before making it.’

‘Very well,’ he snapped. ‘Take all the time you want; it won’t make any difference. We’ll discuss it tomorrow.’

I breathed a sigh of relief. I would read Moral Treatment after dinner this evening and have whatever arguments it contained for my ammunition. As I followed him along the corridor, though, the thought came to me, why do I want to argue with him? Why should I of all people care so much about the treatment of these lunatics, I who was wholly ignorant of such things not twenty-four hours ago? Why put myself at risk by stirring the waters of this safe harbour, given what the consequences might be? But all that carried no weight. I knew I would continue on this course even though to do so lacked any sort of logic. What a piece of work is man! So full of contradictions. I thought not to find such compassion in myself. It troubled me to discover I knew so little of me.